LOOKING AT THE NIGHT SKY

NAKED EYE OBJECTS

The easiest way to start learning about the night sky is simply by looking at it. For thousands of years before the invention of the telescope, all astronomical observations had to be done with just the naked eye. Despite this limitation, people were able to learn an incredible amount by watching how these different points of light drifted around in the sky. By the time Galileo Galilei pointed his refractor telescope at Jupiter, humans had already come up with complex mathematical models for how the planets moved and developed calendars to predict celestial events. With that in mind, just go outside on a clear evening with nothing but your eyes and simply look up. What do you see?

As the Sun begins to sink under the western horizon, you’ll start to see small points of light appear in the sky. Just a few at first, but as the sky darkens, you’ll see more and more of them pop in, one after another. You probably know these to be distant stars. When twilight finally fades completely, you should be met with hundreds or possibly thousands of stars scattered across the darkness of the cosmos. How many stars you can see will depend on how much light pollution is in your area. The further away you can get from bright city lights, the more you’ll see in the sky.

If you look closely at each individual star, you’ll see that they aren’t all the same. Some are brighter than others, though dimmer stars will far outnumber the bright ones. The brightest star in the night sky is Sirius. It is 1,000 times brighter than the dimmest stars you can see. Sometimes a star’s apparent brightness is because it intrinsically shines brighter but other times it may be because the star is closer. This can sometimes lead one to mistake bright stars as being near each other when in fact they are actually very far apart. You’ll also notice that stars can be different colors. Some are blue, yellow, orange or red but most of them just appear white. In the summertime, you can see a particularly dense concentration of stars appearing like a huge, misty streak across the sky. This is the galactic plane of the Milky Way galaxy, which our solar system and every other star we can see in the sky is a part of!

There are some objects in the sky that look like stars but do something that we don’t see stars do. They move. These objects are actually planets. Yes, believe it or not, you can see most of the solar system’s planets without a telescope. There are five naked eye planets: Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn. They can be seen moving across the sky against the relatively motionless background stars (stars do in fact move but are simply too far for us to perceive it). It’s then fitting that the word planet in Greek means “wanderer.” Our view of the moving planets is the result of the counterclockwise orbit of the planets around the Sun, including our own. They roughly follow the same path in the sky as the Sun as all planets have roughly the same orbital plane (looking almost flat from the side). The closer a planet is to the Sun the faster it moves.

Throughout this process, you’ll likely see many different phenomena happening in sequence or simultaneously. Some of these you may understand and others you may have questions. Why does the sky change color at sunset? Why can you see the Moon in the daytime but not the stars? What even are stars and why do they glow? How come some stars appear to zip across the sky in an instant before disappearing? If you’re not used to paying attention to the sky in this way, you may take all these phenomena for granted as things that just simply are. However, all these things have a reason for happening the way they do, and these reasons are knowable. All great scientific endeavors begin with an observation followed by a question. That’s when the fun part begins.

Note: You can learn much more about astronomy you can do with the naked eye by checking out Dale Lehman’s blog series, Eye Astronomy.

CONSTELLATIONS

Humans have always been pattern-seeking machines so it’s no wonder that every generation has looked up at the scattered distribution of stars across the sky and seen all manner of images, albeit to mixed results. These come in the form of constellations, groupings of stars that form a recognizable pattern and often are connected via imaginary lines. These patterns, of course, are largely coincidental and two stars that appear close to each other can often be dozens to thousands of light years apart.

Admittedly, some constellations require more imagination than others. One of the most interesting things about different cultures is that when they look up into the night sky, sometimes they see the same things as each other and sometimes they see something totally different. From these differing interpretations, one can glean the values and experiences of those cultures. Take the constellation Scorpius, for example. Its very distinct pattern has led most cultures to recognize it as a scorpion, yet there are Polynesian traditions that recognize it instead as a shark or stingray.

Since 1922, the International Astronomical Union (IAU) has recognized 88 official constellations. They have defined boundaries, kind of like states, that together cover the entire sky. The most useful thing about being able to identify constellations is that they act as a map for which you can find deep sky objects such as galaxies, nebulae and star clusters.

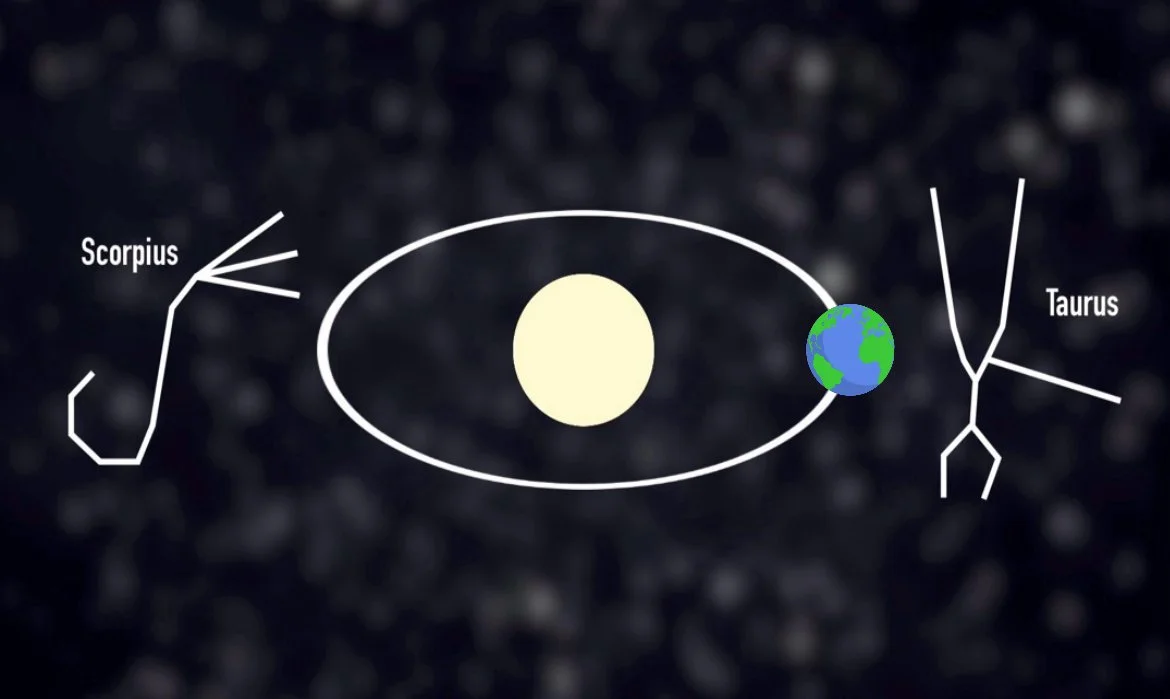

Of these constellations, there are twelve that are known as the zodiac constellations. These are constellations that are occupied by the ecliptic, the path that the Sun crosses throughout the year. Ancient cultures used the Sun’s position within these constellations to track the time of year for agricultural purposes and holidays.

Learning the constellations can be a great way to learn the sky. They break it up into smaller, more manageable pieces and can become useful reference points to find more specific objects. Why not test yourself? Anytime you happen to be outside at night for whatever reason, challenge yourself to find a pre-selected constellation. I would start with the zodiacs first before moving on to the more obscure ones. A little trick you can use is to find the constellation’s brightest star, like the blue star Spica in Virgo.

There are some recognizable patterns that aren’t considered official constellations, but are nonetheless quite well-known, called asterisms. One example would be the Summer Triangle, a simple asterism made up of three bright stars that are high in the sky during the summer months: Vega, Deneb and Altair. Sometimes asterisms are found as part of larger constellations. The most famous example would be the Big Dipper which, while very recognizable, is often mislabeled as a constellation. It is actually part of the Ursa Major constellation, also known as the Big Bear.

Fun fact: You can use the Big Dipper to guide you to Polaris, the North Star. Draw an imaginary line through the two stars at the end of the bowl and extend it five times further. You will end up at Polaris.

THE CHANGING SKY: LUNAR & SEASONAL CYCLES

As you continue to watch the sky over time, you’ll notice that it doesn’t stay the same. Across the year, across the month, even throughout a single night, you’ll see that nothing is quite as it was before. Things are always moving around in different ways.

The most obvious of these changes is the day-night cycle. Each morning, the Sun rises above the horizon, lighting up everything and bringing the daytime. It moves across the sky throughout the day and then sets below the opposite horizon in the evening. Everything gets dark, the stars come out and nighttime begins. This whole cycle of day and night lasts just over 24 hours. While it may appear that the Sun and sky are the ones moving around the Earth, it is actually the Earth’s own rotation that causes this.

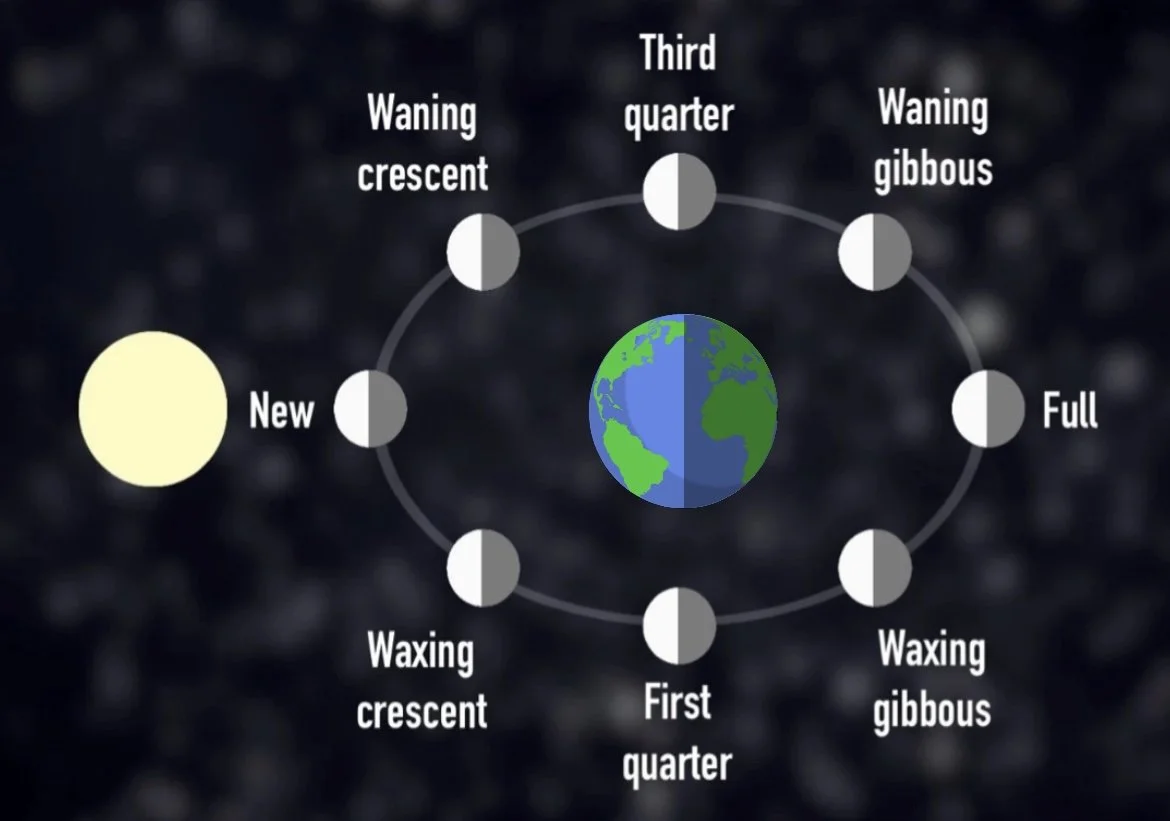

Another thing that changes regularly is the Moon, the giant rocky sphere that floats in the sky. Each night, you’ll notice the Moon is in a different position against the background stars and planets. Specifically, it is always east of where it was the night before. This is because the Moon is orbiting around the Earth (learn more about orbits in the gravity primer). For now, just know that the Moon is moving counterclockwise around the Earth, roughly in a circle.

Note: Remember that while the Moon’s orbit moves it across the sky in an eastward direction, the Earth’s faster rotation makes the Moon appear to move westward. Kind of like how a slower car appears to move backwards when overtaken by a faster car.

As the Moon orbits Earth, you’ll notice different parts of the Moon are lit up, creating the lunar phases. The Moon doesn’t produce its own light; it reflects sunlight. At any moment, half of the Moon is illuminated by the Sun, just like half of Earth is in daylight. However, because the Moon is constantly moving around Earth, the angle between the Moon, Earth, and Sun shifts. This changing angle alters how much of the day and night side we can see from Earth. As the Moon moves away from the Sun, we see more of its illuminated side. When the Moon is opposite the Sun, we see it fully illuminated, known as a full moon. As it continues in its orbit and moves back toward the Sun, we see less of its illuminated side. It eventually reaches its closest point to the Sun, known as a new moon, when the dark side directly faces us. Thus begins the cycle anew, lasting about a month.

We can see significant changes that span the whole year as well. For example, certain constellations are only visible during certain times of year. Taurus is best seen in the winter while Scorpius is best seen in the summer. This is because, just like how the Moon orbits Earth, the Earth orbits the Sun. It takes about 365 days, or a year, to do a full revolution.

This becomes another reason to know the constellations as it can give you a heads up on what will or won’t be visible across the year. If you know that Taurus is a winter constellation, you’ll know not to look for its best star cluster, the Pleiades, in July and know how long you’ll have to wait before you can.

Note: Stars rise and set about four minutes later than the previous evening due to Earth’s orbit around the Sun.

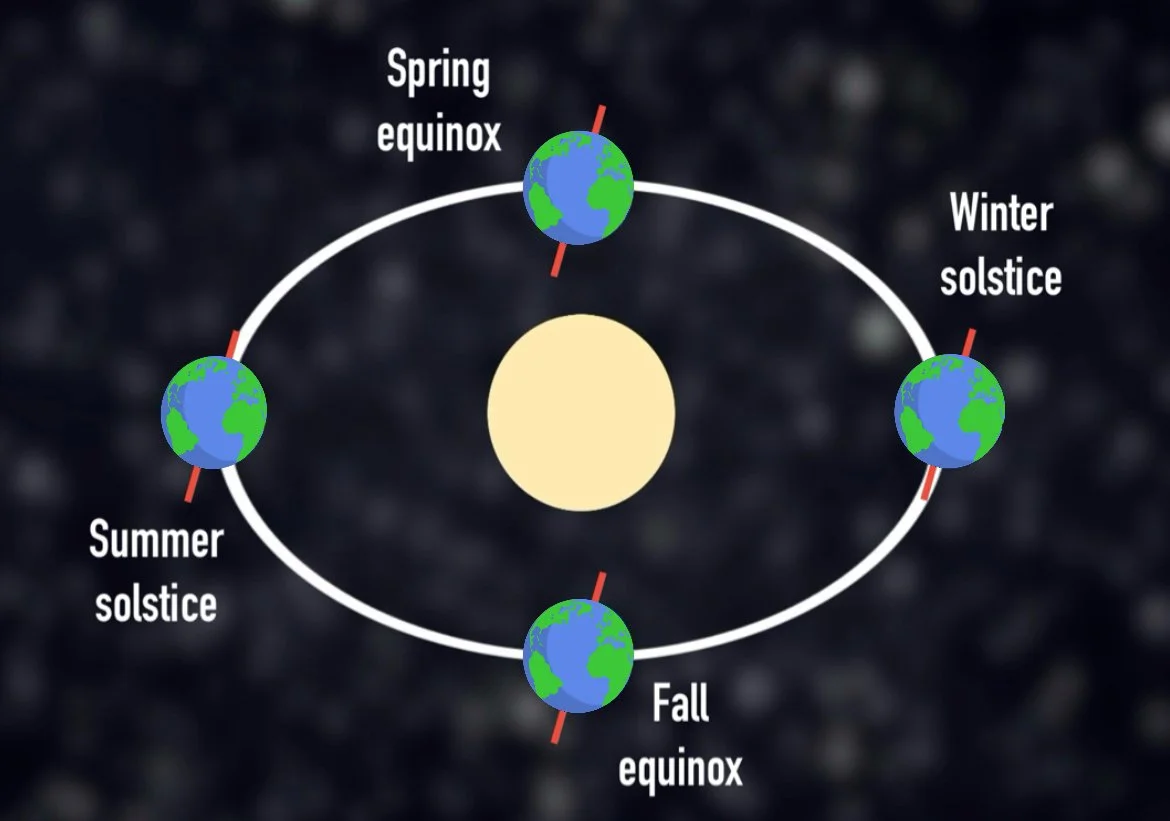

Speaking of seasons, in the summertime, you’ll see that daylight lasts longer, and the Sun reaches higher in the sky. Meanwhile, in the wintertime, you’ll see that daylight is shorter, and the Sun reaches lower in the sky. This is because the Earth is tilted on its rotational axis by 23.5°. As Earth moves position around the Sun, it changes the orientation of its axial tilt.

When the northern hemisphere is tilted toward the Sun, it receives more direct sunlight and becomes warmer. This marks the start of summer, or the summer solstice. Six months later, when it tilts away from the Sun, the light is more slanted and spread out, causing the temperature to drop and signaling the start of winter. In between, when the tilt is more perpendicular to the Sun, we get the equinoxes that herald the transitional seasons: spring follows winter, and fall follows summer.

Note: The seasons are opposite between the northern and southern hemispheres. When it’s summer in the north, it’s winter in the south, and when it’s spring in the north, it’s fall in the south.

THE CELESTIAL SPHERE

If you’re going to spend time looking at the night sky, you’ll need to get your bearings. With so many objects to see, some of which never stay in the same spot, it’s very easy to get turned around and lose track of what is where. This is why astronomers across the centuries have taken great effort to organize the sky and provide tools to help guide you.

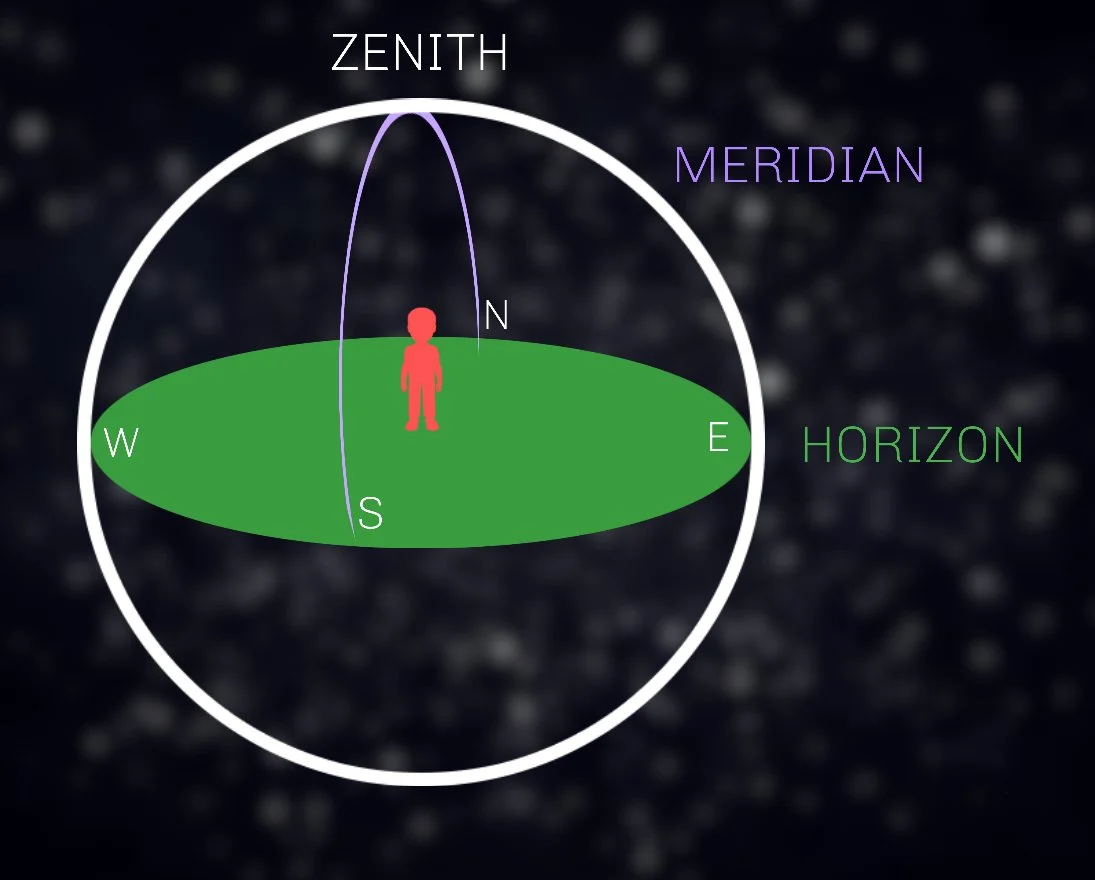

Before we worry about objects in space, let’s get ourselves oriented with the basics. As you are standing on Earth’s surface, the bottom half of what you can see is on the ground and the top half of what you can see is in the sky. The line, or rather the circle, that separates these two realms is called the horizon. You can see the horizon in every direction and we organize these directions into four quadrants, called cardinal points: north, south, east, west. There is a broader context to why north is north and west is west but we’ll get into that later. For now, just find and face north.

From where you stand, look straight up. Mark an imaginary point in the sky directly above your head. This is called the zenith. This point is always relative to the person. Because the Earth is a sphere, your zenith will not be where someone else’s zenith will be. Now, from the most northern point on the horizon, draw an imaginary line up into the sky that crosses through the zenith and returns back down and meets the southern horizon. This line is called the meridian. Its significance, too, will become important later.

Let’s review: We have the horizon which separates the ground from the sky. We can look north, south, east and west. We have the zenith up above and the meridian passing through it from north to south.

Now let’s zoom out and check out the celestial sphere!

The celestial sphere is a representation of the night sky in the form of a larger transparent sphere surrounding the Earth. On the sphere are numerous lines, some of which wrap around the sphere itself and form a circle while others extend out from the Earth and connect with it.

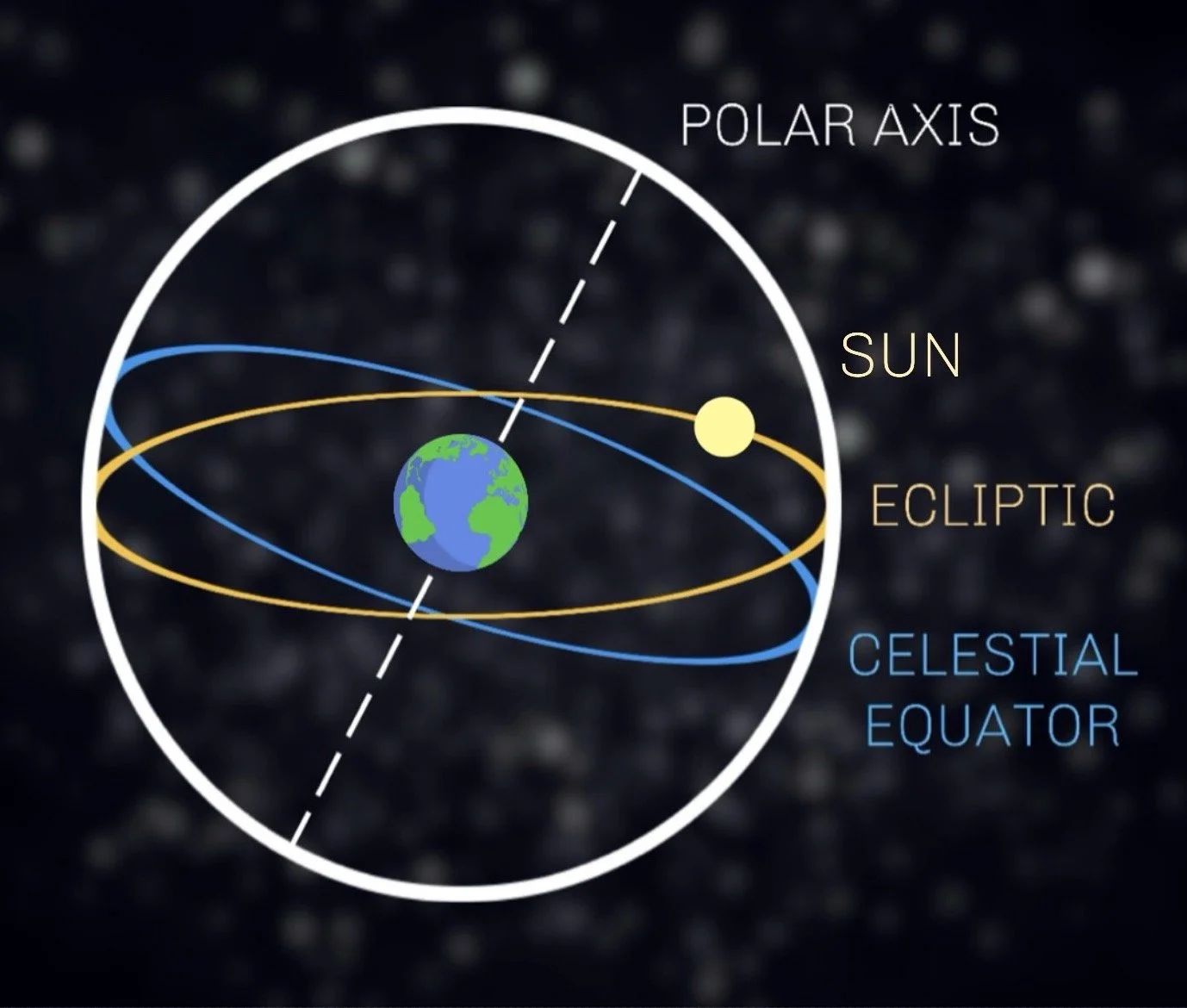

The first of these lines is the celestial equator. This is basically the same as the Earth’s equator but projected out onto the sky, forming a wide circle around the Earth. Simple enough.

Perpendicular to the celestial equator is a straight line that extends directly through the Earth from top to bottom. The top end of this line is called the north celestial pole, and the bottom is the south celestial pole. The northern side of the polar axis is pointing towards the north star, Polaris. It is around this axis that the sky and everything in it appears to rotate (due to Earth’s counterclockwise rotation).

The next line is called the ecliptic. It is a circle around the Earth just like the celestial equator but inclined at an angle with half of it above the celestial equator and the other half below it. The ecliptic defines Earth’s orbital plane and the apparent path that the Sun moves across the sky. Each day, the Sun appears to move about 1° counterclockwise around the ecliptic, constantly shifting its position against the background stars. Remember, what’s actually happening is the Earth is orbiting around the Sun.

The ecliptic is inclined to reflect Earth’s 23.5° axial tilt relative to its orbital plane, which you’ll remember is responsible for the seasons. When the Sun reaches the highest point on the ecliptic above the celestial equator (right side on the image), Earth’s northern hemisphere is tilted toward the Sun, marking the summer solstice. When the Sun is at the lowest point below the celestial equator (left side on the image), the northern hemisphere is tilted away, marking the winter solstice. The points where the ecliptic crosses the celestial equator are the vernal and autumnal equinoxes. At these times, both hemispheres receive equal sunlight, signaling the start of spring and fall.

Let’s review: The celestial sphere surrounds and spins around the Earth. The Sun moves along the ecliptic which intersects with the celestial equator at an angle. This is because the Earth is tilted on its axis.

When studying the celestial sphere, it’s important to consider your location on the Earth. Where is your zenith? What parts of the celestial sphere are visible from your location or hidden under the horizon? What part of the celestial sphere is visible at night or enveloped in daylight? Think about how the celestial sphere appears to move around you as the Earth rotates. The more you understand these movements, you will begin to see the sky in a very different way.

CELESTIAL COORDINATES

Also often featured on celestial spheres is a grid pattern where the vertical lines converge at the poles and the horizontal lines form smaller and smaller circles towards the poles. Astronomers use this as a system of coordinates in order to locate specific objects in the sky, reminiscent of the latitude and longitude system. Knowing these coordinates are not necessary to enjoy the night sky but they can help if you are getting more serious about it. There are two main systems used: the equatorial system and the horizontal system.

Here’s a quick reference for the units of measurement used to determine the angular distance or size:

Degrees: Segment the circumference of the celestial sphere into 360 degrees. Represented with the ° symbol.

Arcminutes: There are 60 arcminutes in a degree. Represented with the ‘ symbol.

Arcseconds: There are 60 arcseconds in an arcminute and 3,600 arcseconds in a degree. Represented with the “ symbol.

These units can be used to notate the distances and size of things as they appear in the sky.

The Equatorial System

The equatorial coordinate system is based on the projection of Earth's equator onto the celestial sphere. It is the more commonly used of the two because it provides more consistent positions for objects over time and doesn’t need to account for your relative position on the Earth. This is critical if you are trying to relay coordinates to someone who is at a different location on Earth.

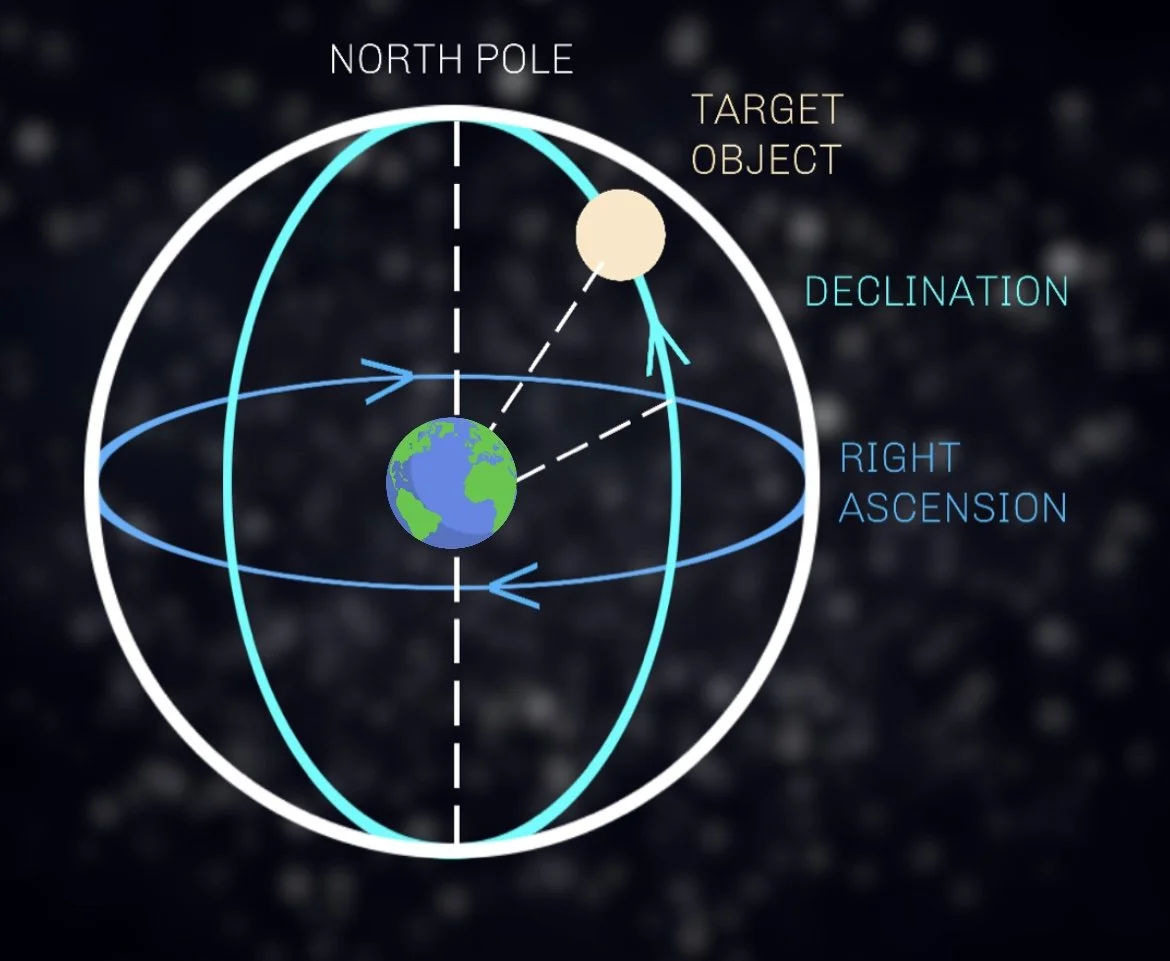

It uses two coordinates: right ascension (RA) and declination (Dec).

Right Ascension (RA): Similar to longitude, right ascension measures the angular distance eastward along the celestial equator starting from the vernal equinox where the ecliptic intersects with the celestial equator at the beginning of spring. It is usually measured in hours, minutes, and seconds. The vernal equinox is considered 0 hours. An hour equates to 15°.

Declination (Dec): Similar to latitude, declination measures the angular distance north or south of the celestial equator. It is usually measured in degrees (°), arcminutes (‘), and arcseconds (“). At the celestial equator, it begins at 0° and goes up to 90° at the north pole and down to -90° at the south pole.

In practice, an equatorial coordinate looks like this:

Sirius

Right Ascension: 06h 45m 09s

Declination: -16° 42’ 58”

The Horizontal System

The horizontal system, also known as the altazimuth system, is used to find the position of celestial objects from your relative location on Earth. This system may be more useful if you are relaying coordinates between people at the same location.

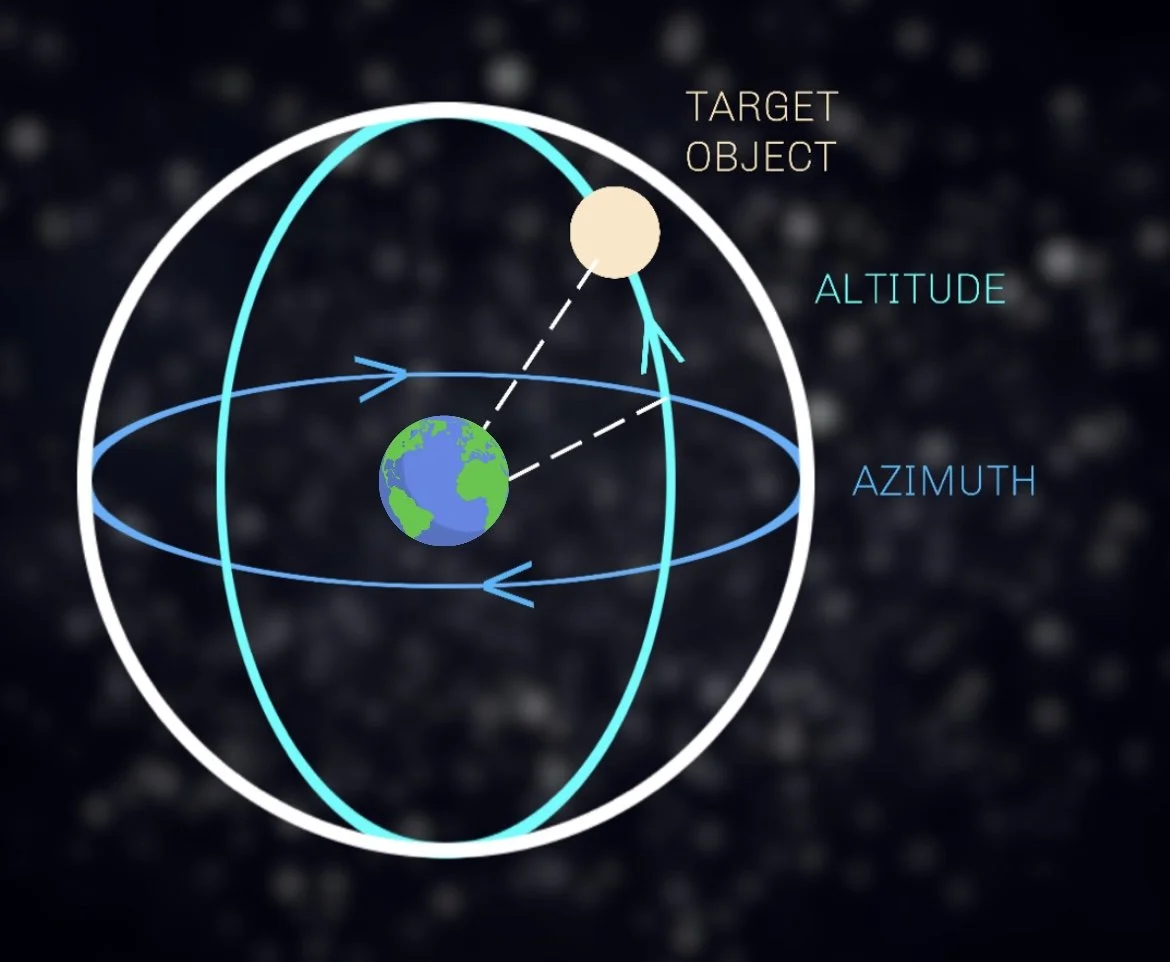

It uses two coordinates: altitude (Alt) and azimuth (Az).

Altitude (Alt): Altitude measures the angle above the horizon. It ranges from 0° at the horizon to 90° at the zenith (directly overhead).

Azimuth (Az): Azimuth measures the angle along the horizon, starting from the north and increasing as you move clockwise with 0° to the north, 90° to the east, 180° to the south, 270° to the west, and then completing a full circle back to north.

In practice, a horizontal coordinate looks like this:

Sirius

Altitude: 45° 30’ 30”

Azimuth: 180° 30’ 30”

To convert between the equatorial and horizontal coordinate systems, one needs to know the observer's location on Earth and the current date and time.

ANGULAR SEPARATION & SIZE

Degrees, arcminutes and arcseconds are not only used for celestial addresses but as a measuring stick for both the apparent distance between celestial points and the size of celestial objects.

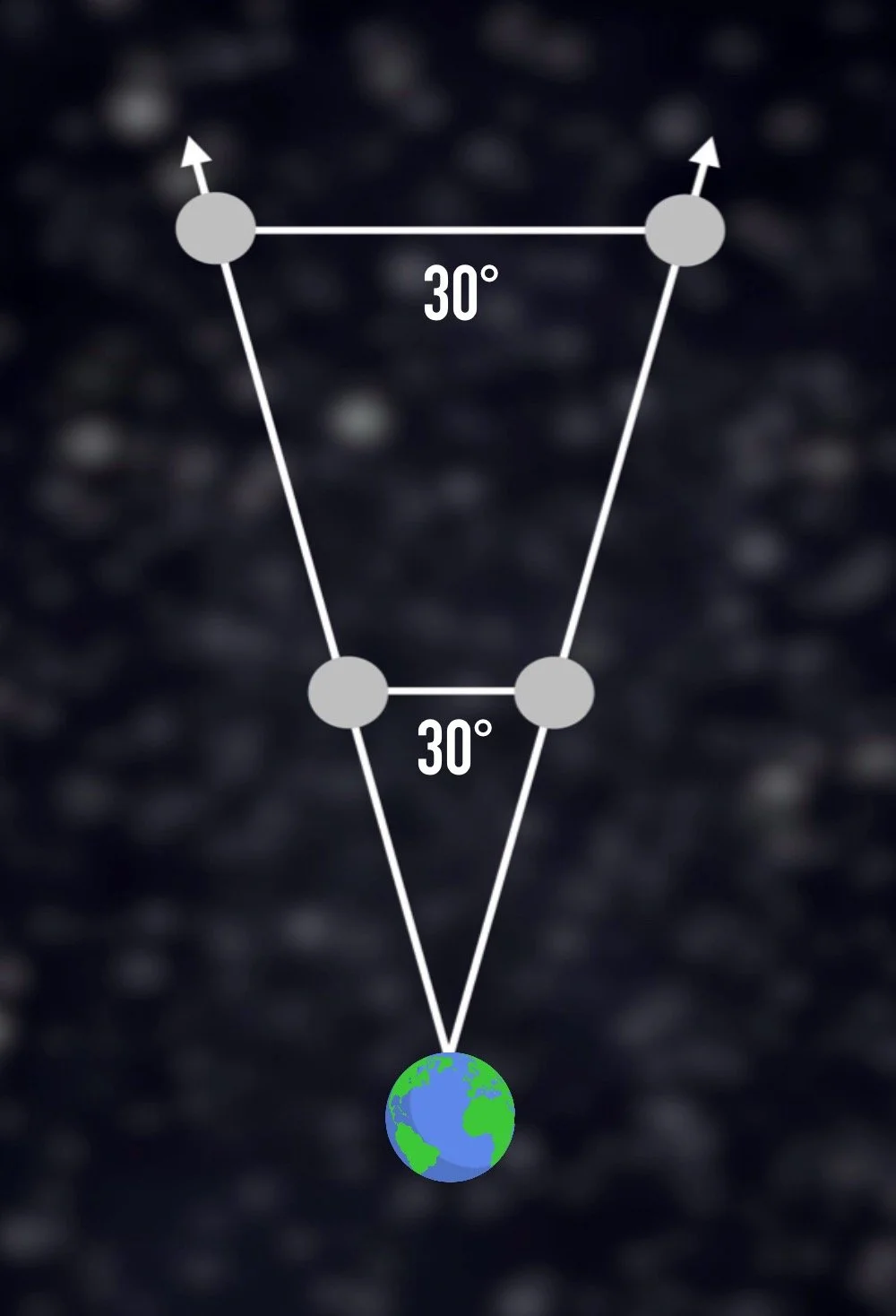

Angular separation deals with the apparent distance between objects. Remember, this is not the actual distance between them but the ‘angle of separation’. This is relative based on their distance from the observer. Two stars with an angular separation of 30° will be much more distant from each other than two planets in our own solar system with an angular separation of 30°.

Angular size deals with the apparent diameter of an object, the size an object appears to be due to its distance. Stars are so far away that even through a telescope they always appear as tiny points of light. The Sun, Moon and planets, on the other hand, are close enough that we can make out their sizes end-to-end.

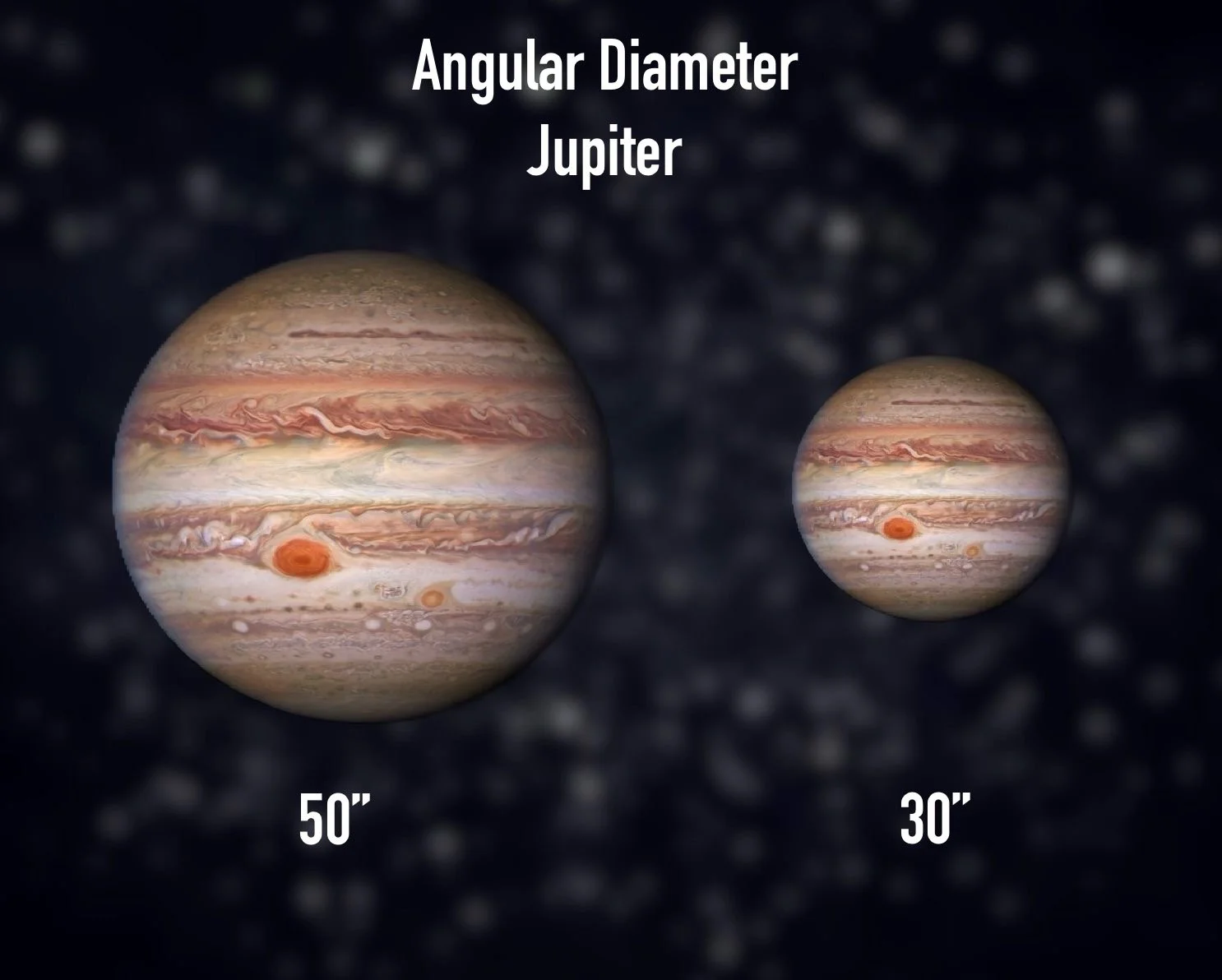

A planet’s angular diameter can change over time as we and the other planet get closer and further from each other as we both orbit the Sun at different speeds and distances. For example, the angular diameter of Jupiter at its closest is 50 arcseconds and at its furthest is 30 arcseconds. Even the Sun’s angular diameter changes subtly throughout the year as Earth’s orbit around it is not perfectly circular.

There are two objects in the sky that have relatively large angular diameters that change very little throughout the year: the Sun and Moon. One because the Earth orbits it and the other because it orbits the Earth. By sheer coincidence, both the Sun and Moon span roughly half a degree at any given time. You can use this as a measuring stick for deep sky objects. If a galaxy has an angular diameter of 2° you know that it is about four full moons across.

POSITIONAL ASTRONOMY

As objects in the night sky move around this way and that way, they sometimes appear to do interesting things from our vantage point.

Sometimes two or more celestial objects will appear very close together in the sky from Earth’s vantage point. This could be the Moon and a planet, a planet and a star, two planets, etc. This is usually due to line of sight, not physical distance. These close encounters are known as conjunctions and are relatively common amongst objects within our solar system due to them sharing similar orbital planes. On very rare occasions they can even pass so close that a telescope must be used to resolve them separately.

Sometimes objects can get so close that one passes directly in front of another. There are different words to describe this depending on the circumstances. If the foreground object is smaller than the background object, this is known as a transit. An example is when Mercury or Venus pass in front of the Sun. If the foreground object is bigger than the background object, this is known as an occultation. An example is when the Moon passes in front of a planet or star. If one object moves into another object’s shadow, this is known as an eclipse. We experience two kinds of eclipses here on Earth. Lunar eclipses occur when the Moon passes into the Earth’s shadow while solar eclipses occur when the Earth passes into the Moon’s shadow.

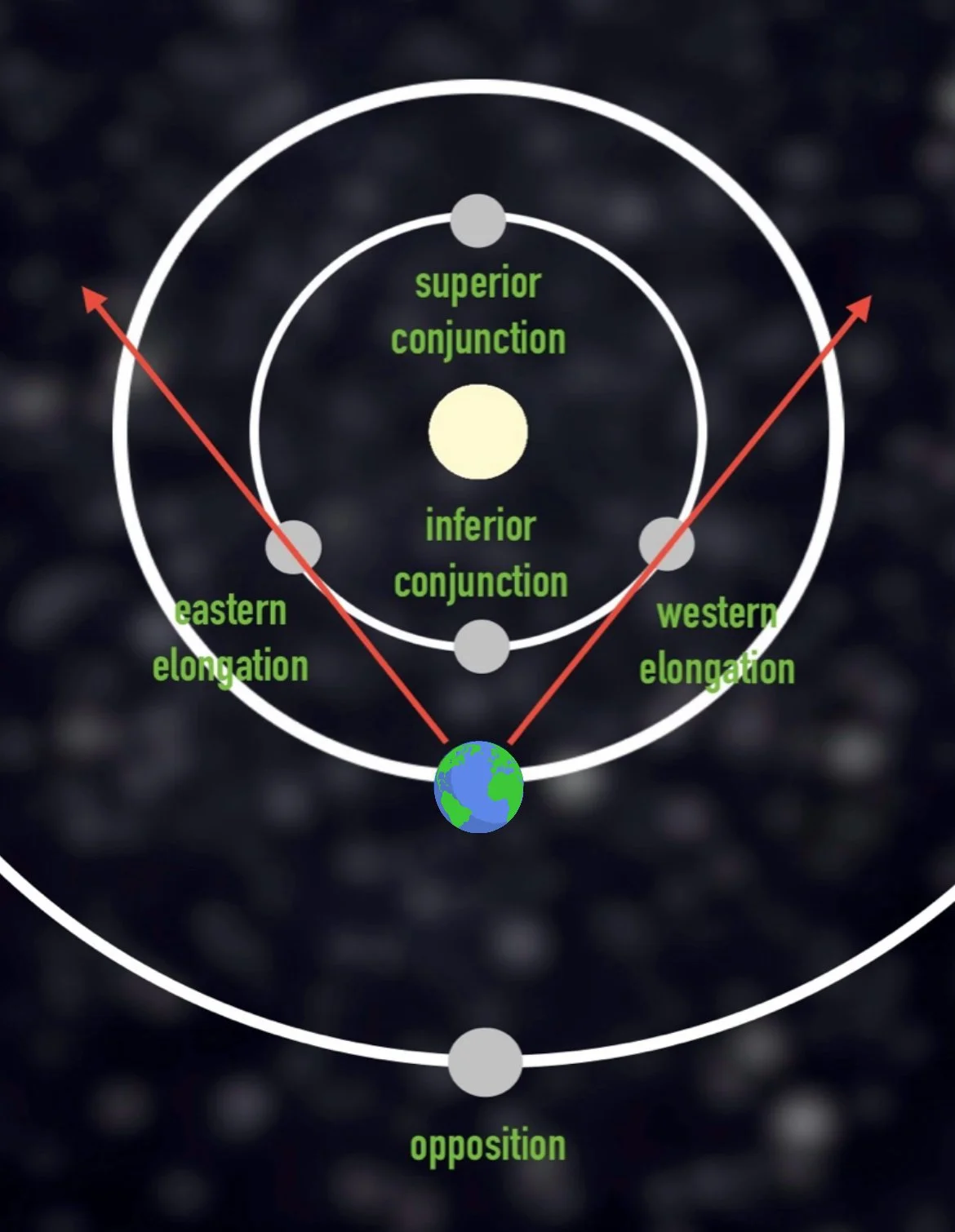

When an object that orbits the Sun, like an asteroid or a planet, lies directly opposite the Sun, or rather the Earth lies between the Sun and the object, that is known as opposition. There are a few reasons these are often opportune times to view that object. First, it rises at sunset and sets at sunrise, meaning it is visible in the sky throughout the entire night. Second, this usually marks the object’s closest proximity to Earth for the year and therefore has the largest angular size. This alignment is only possible with objects that orbit further from the Sun than Earth does. These objects are known as having superior orbits.

There are also objects that have inferior orbits to Earth, meaning they orbit closer to the Sun. These would be the planets Mercury and Venus. Their orbits appear to keep them leashed to the Sun and are never able to reach opposition like superior planets can. As they orbit around the Sun, they get further away from it reaching higher into the sky until they get to a point known as greatest elongation. This is the point of maximum separation between the planet and the Sun from Earth’s vantage point. If it is visible after sunset, it is known as eastern elongation. If it is visible before sunrise, it is known as western elongation. After reaching this point, the planet will start to drift back towards the Sun, eventually passing it and appearing on the other side.

The night is vast and full of wonder. Taking the time to appreciate its beauty and complexity can itself be a gratifying experience but at times may even feel overwhelming.

If you or anyone you know are looking for guidance on learning how to navigate the stars and planets, members of the Harford County Astronomical Society are here for you to provide our enthusiastic knowledge and experience.

Come find us at future events or fill out an outreach request form and ask for assistance and we will do what we can!