STARS

WHAT IS A STAR?

When we look up at the night sky, we see it is filled with tiny points of light. Some brighter, some dimmer. Some red, some blue, but most are white. Ancient people speculated that they were divine beings of some kind. Others thought they were fiery stones embedded in the cosmic dome above, or maybe holes in the sky letting through light from some otherworldly domain. Few clever thinkers even wondered if they were incredibly distant Suns. That is, in fact, what they are. But let’s be very concise on what a star really is.

Simply put, a star is a gigantic, luminous sphere of scorching gas held together by its own gravity.

HOW DO STARS FORM?

The life of a star begins with a giant molecular cloud, a type of nebula. These vast, cold volumes of thick gas and dust often span dozens of light years across. They consist primarily of hydrogen and helium, the most abundant elements in the universe. There can be various heavier elements like carbon, oxygen and iron recycled from the explosive deaths of previous generations of stars.

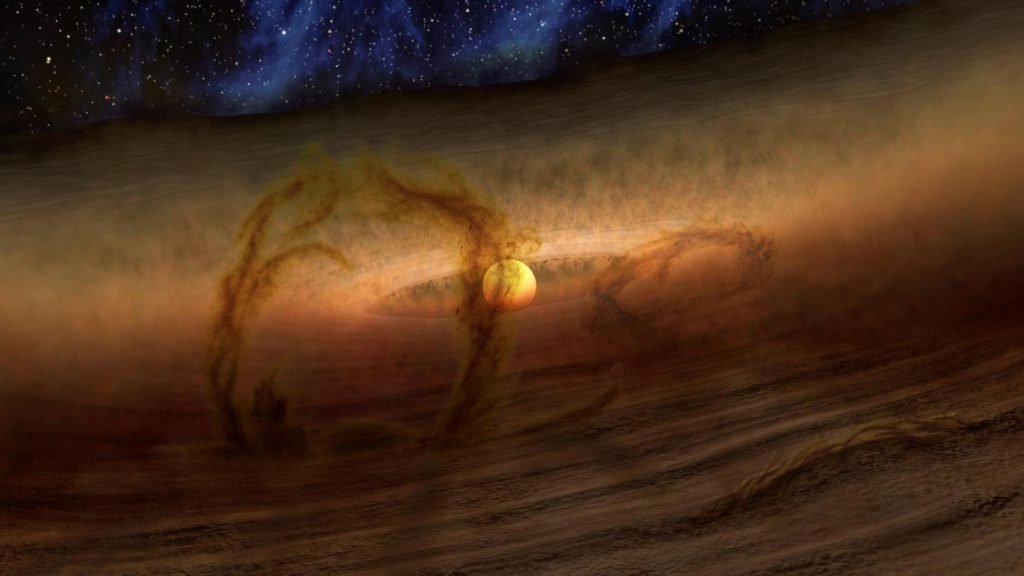

The higher gravity of denser regions within the cloud begin to overcome its internal gas pressure. Numerous of these regions coalesce into denser cores. This can take millions of years. These gravitationally-bound cores are the precursors to protostars, hence why these clouds are often called “stellar nurseries.” As they continue to collapse, temperatures rise dramatically at their centers. As the cloud drifts through the cosmos, it can also be subject to various other influences, including shock waves from nearby supernovae or collisions with other clouds, which can trigger the process of star formation.

Pictured is the Orion Nebula (M42), found 1,300 light years away in Orion, which is well-known to facilitate active star-formation.

By this point, the protostar is glowing hot from the internal pressure it endures by its own gravity. However, its luminosity remains cloaked by the thick, swirling cocoon of gas and dust that has begun to churn around it like a frenzied whirlwind. As gravitationally-bound material falls inward, their angular momentum is conserved by accelerating into smaller, faster orbits.

While some kind of common direction and plane of motion is likely to develop early on, this period of a star’s infancy is still characterized by intense violence and chaos. Trillions of objects, big and small, are yanked around by each other’s gravity, crossing paths and colliding over and over. Some debris is broken into smaller fragments while other collisions allow objects to merge into bigger ones. Over time, these countless collisions between overlapping orbits continuously transfer momentum and change trajectories until they coalesce into one synchronous flattened orbit called an accretion disk.

As the inner region of the accretion disk spirals around the growing protostar at high velocity, losing mass quickly, the outer regions around the disk accumulate and grow denser themselves. Low-velocity collisions allow dust grains and pebbles to stick together to form meter-sized rocks which in turn form kilometer-sized planetesimals. As these rocky cores of material grow, they generate stronger gravitational fields which attracts even more material. This creates a runaway growth in which the large bodies grow faster than the smaller ones. These various objects will become the planets, moons and asteroids that will populate the star system.

The protostar continues to ingest the inward spiraling matter of the surrounding accretion disk, increasing its mass and gravity. This creates more and more compression within the interior of the fledgling star, causing its temperature to rise higher and higher. Eventually, this will trigger thermonuclear fusion and thus the protostar becomes a fully-fledged star. This process from the gravitational collapse of a giant molecular cloud to the beginning of thermonuclear fusion can take just a few million years for a very high mass star, tens of millions of years for an intermediate star, and more than a hundred million years for a very low mass star.

STELLAR MASS

A star’s mass is possibly the most crucial metric that determines many other aspects of its existence. The more mass a star has, the stronger its gravity. This affects its luminosity, temperature, color, size, internal structure, lifespan, evolutionary path and ultimate fate.

We typically communicate the mass of stars using the solar mass unit (M☉), which represents the mass of our Sun. If a star has twice the mass of the Sun, we say it has two solar masses or 2 M☉. If a star has half the mass of the Sun, we say it has half a solar mass or 0.5 M☉. Keep in mind that a star’s solar mass does not necessarily correlate to its size compared to the Sun.

Some stellar objects or sub-stellar objects that are very low mass will sometimes be referred to by their Jupiter mass (MJ). This is to say, how many times more massive the object is than Jupiter. These are objects like brown dwarfs which are several dozen Jupiter masses. The smallest red dwarf stars may also use this unit instead of solar masses.

THERMONUCLEAR FUSION

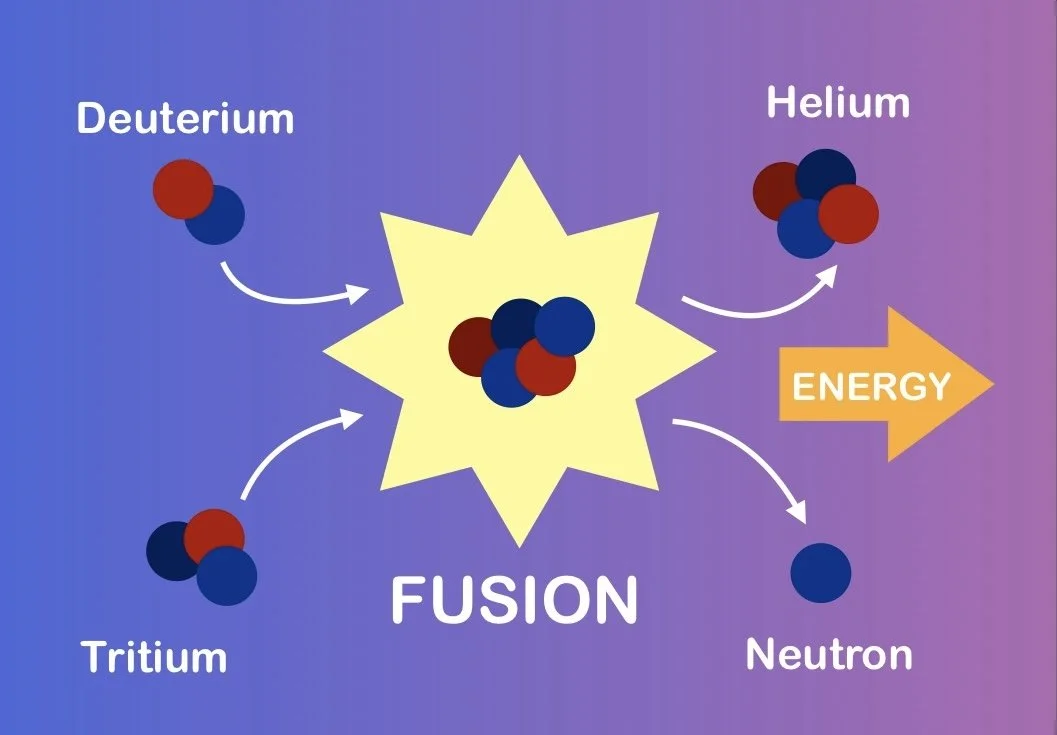

Stars are made up of mostly hydrogen and helium, the two most abundant elements in the universe. As a protostar accrues mass, its gravity becomes stronger, which in turn can pull in more mass, creating a feedback loop. The increasing gravity creates extreme pressure within the infant star, especially at the very center. Atoms being squeezed this intensely start colliding with each other and generate energy in the form of heat. The temperature rises faster and faster until it reaches millions of degrees. When the temperature reaches a particular threshold, hydrogen atoms begin to fuse together to create helium atoms. This process is called thermonuclear fusion and is what makes something a star.

In the process of fusion, some of the mass of the atoms is converted into energy (see Einstein’s mass-energy equivalence principle). The energy is emitted outward in the form of light and heat, carried away from the core through a combination of radiative and convective heat transfer processes. The outward force of the star’s radiating energy is matched against the inward force of the star’s own gravity. This balance is called hydrostatic equilibrium and is what holds the star together in a stable form. Eventually, the energy traverses the star's interior, escapes and then radiates into outer space. This is why stars shine and heat their surroundings.

As a star’s core temperature gets higher, it can trigger the fusion of progressively heavier elements (such as helium into carbon, carbon into oxygen, etc.). This produces even more energy, and the heavier elements make the core denser which in turn increases the temperature. Stars of a particular mass will eventually be unable to reach the necessary temperature threshold to fuse certain elements. We will talk about what happens then at a later point.

STAR CLASSIFICATION

Even a quick naked eye glance at the stars in the night sky can tell you that they are not all the same. Some stars are brighter than others. Some are different colors. Some act quite erratically while others are relatively mellow. We are able to determine much about a star simply by what it looks like. Not that we have much choice. The closest stars are much too far for us to travel to in any sort of reasonable time frame. Therefore, we must once again rely on our cleverness and build on our previous understandings. Particularly, we must look at the spectra of their starlight.

A spectrograph breaks down starlight into its component colors and allows astronomers to analyze the patterns of emission and absorption lines. From this, they can derive all kinds of vital information about the star, from composition to temperature.

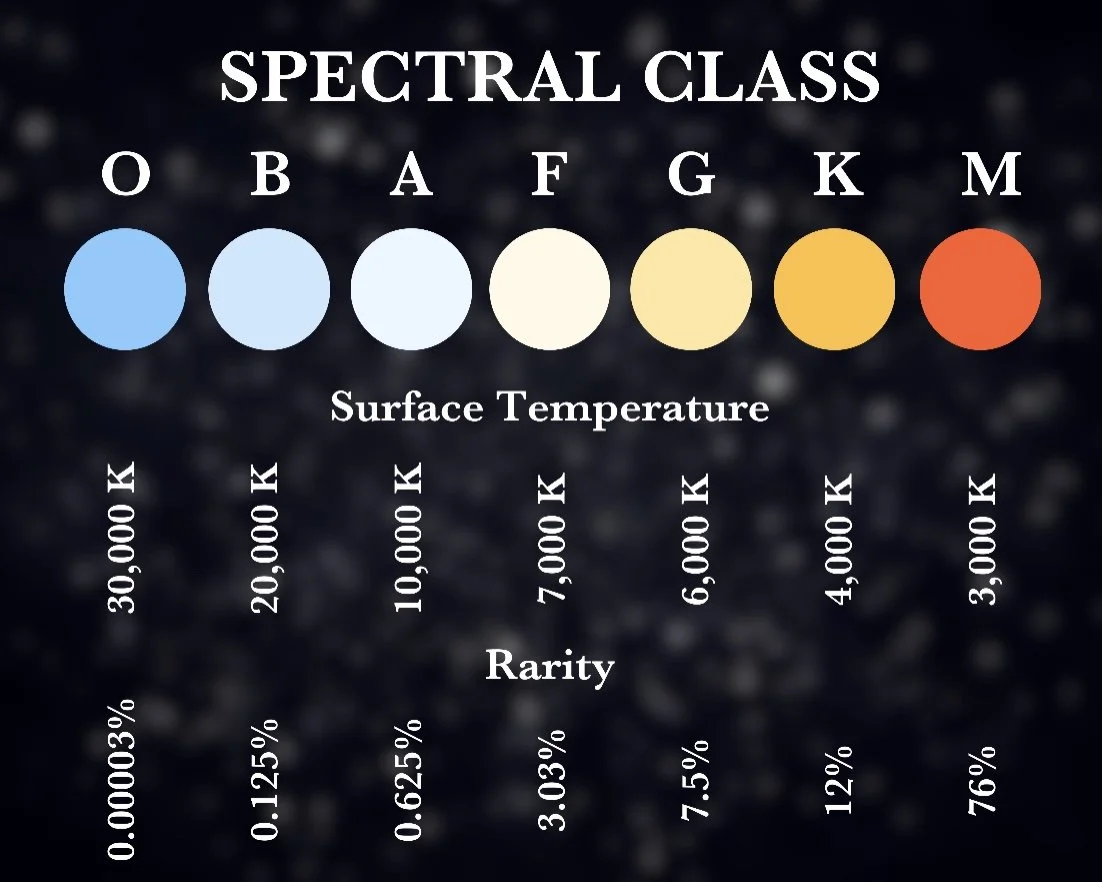

Stars are classified by their spectral characteristics via the Morgan–Keenan (MK) system using the letters O, B, A, F, G, K and M, a sequence from the hottest (O-type) to the coolest (M-type). Each letter class is often subdivided using a numeric digit with 0 being hottest and 9 being coolest. There are also classifications for special types of stars or star-like objects such as class D for white dwarfs and classes S and C for carbon stars.

A luminosity class is sometimes added to the spectral class using Roman numerals. Luminosity class 0 or Ia+ is used for hypergiants, class I for supergiants, class II for bright giants, class III for regular giants, class IV for subgiants, class V for main sequence stars, class sd (or VI) for subdwarfs, and class D (or VII) for white dwarfs.

The full spectral class for the Sun is then G2V, indicating a main sequence star with a surface temperature around 5,800 K.

Examples:

O-type: Alnitak, Mintaka

B-type: Spica, Rigel, Regulus

A-type: Vega, Sirius, Alioth

F-type: Procyon, Polaris

G-type: Sun, Capella

K-type: Pollux, Arcturus, Aldebaran

M-type: Betelgeuse, Proxima Centauri

How come we don’t see any green or violet stars? Well, stars do in fact emit these colors but never exclusively so. A star radiating from the center of the visible spectrum, where green is prominent, will also radiate all other colors and therefore appear white, like our Sun. Hotter stars emitting shorter wavelengths of the visible spectrum will radiate violet but will also radiate blue which has a wider range of wavelengths and human eyes are much more attuned to blue. You’ll also never see a star peak both in the red and blue (and thus not see them combine to make violet).

While it is not unusual to see star temperature recorded in Celsius, it is the international scientific standard to measure a star’s temperature using Kelvins (K). This unit is basically identical in its scaling but starts at absolute zero (the coldest temperature attainable). To convert a temperature from Celsius to Kelvin, you simply add 273.15. To convert Kelvin to Celsius, you subtract that number instead. All that being said, considering the extreme temperatures associated with stars, the difference between Celsius and Kelvin is pretty negligible.

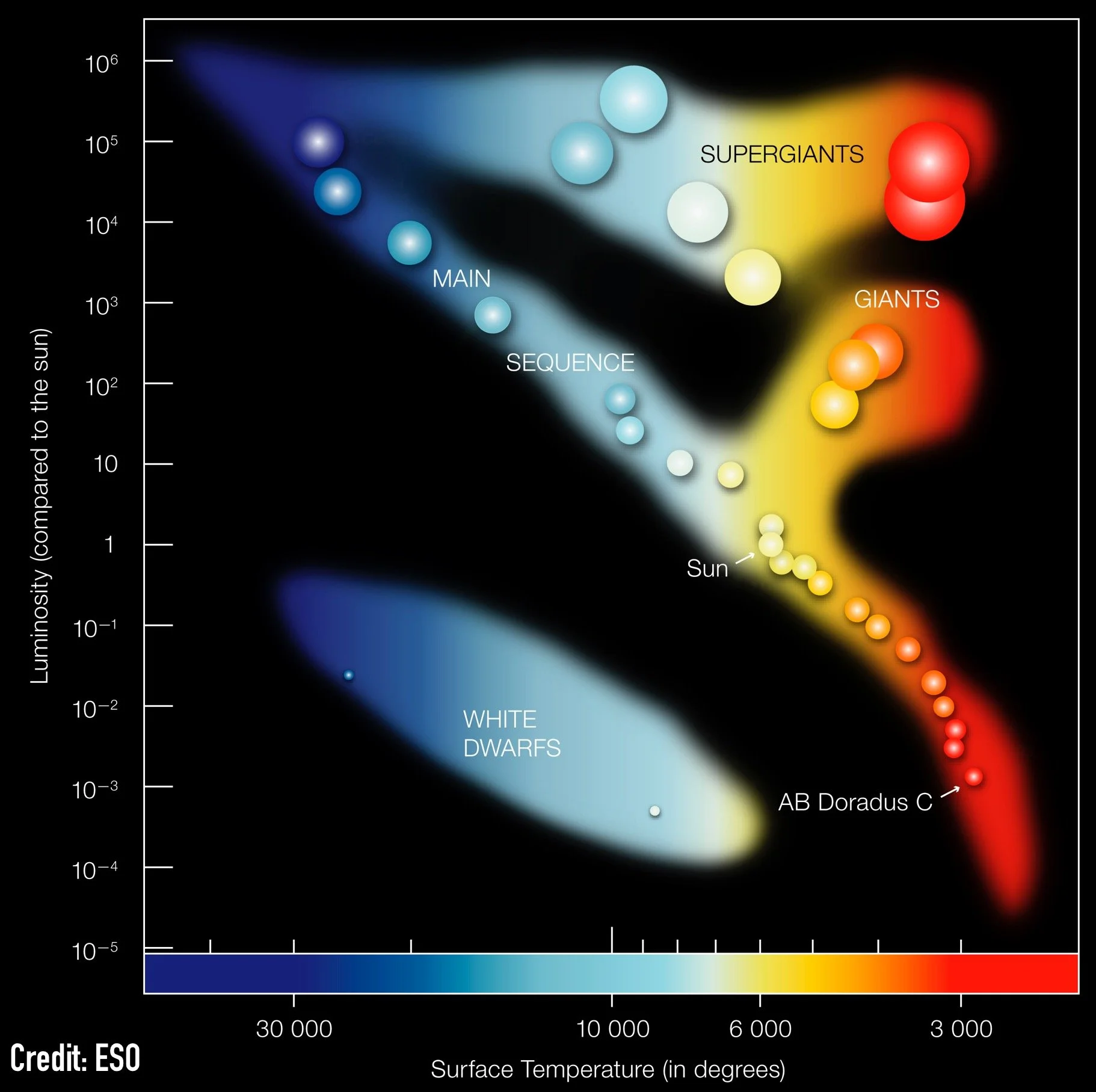

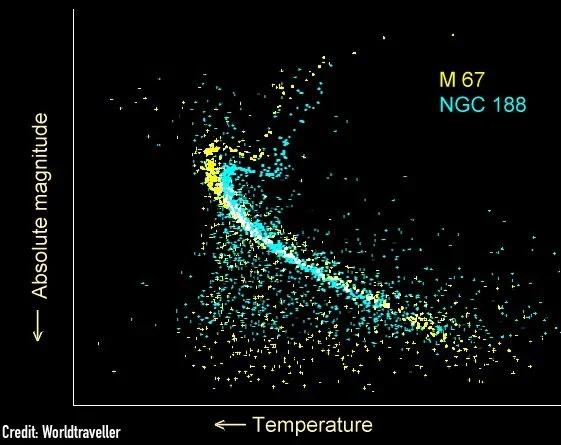

We find something very interesting when we examine these spectral characteristics for patterns and trends. Possibly one of the most important diagrams in all of astronomy, the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram is a scatter plot of stars showing the relationship between stars’ luminosity (absolute magnitude) versus their surface temperatures (or corresponding spectral types).

A pattern known as the main sequence stretches across from the upper left (hot, blue, luminous stars) to the bottom right (cool, red faint stars) and dominates the HR diagram. About 90% of the universe’s stellar population is on the main sequence and they will spend about 90% of their lives burning hydrogen into helium in their cores and generating outward radiating energy which maintains a balance against their inward gravity. Where a star appears on the main sequence is largely a product of its mass. Stars that appear outside of the main sequence have ceased regular activity and are either becoming unstable and nearing the end of their life or are the remnants of dead stars.

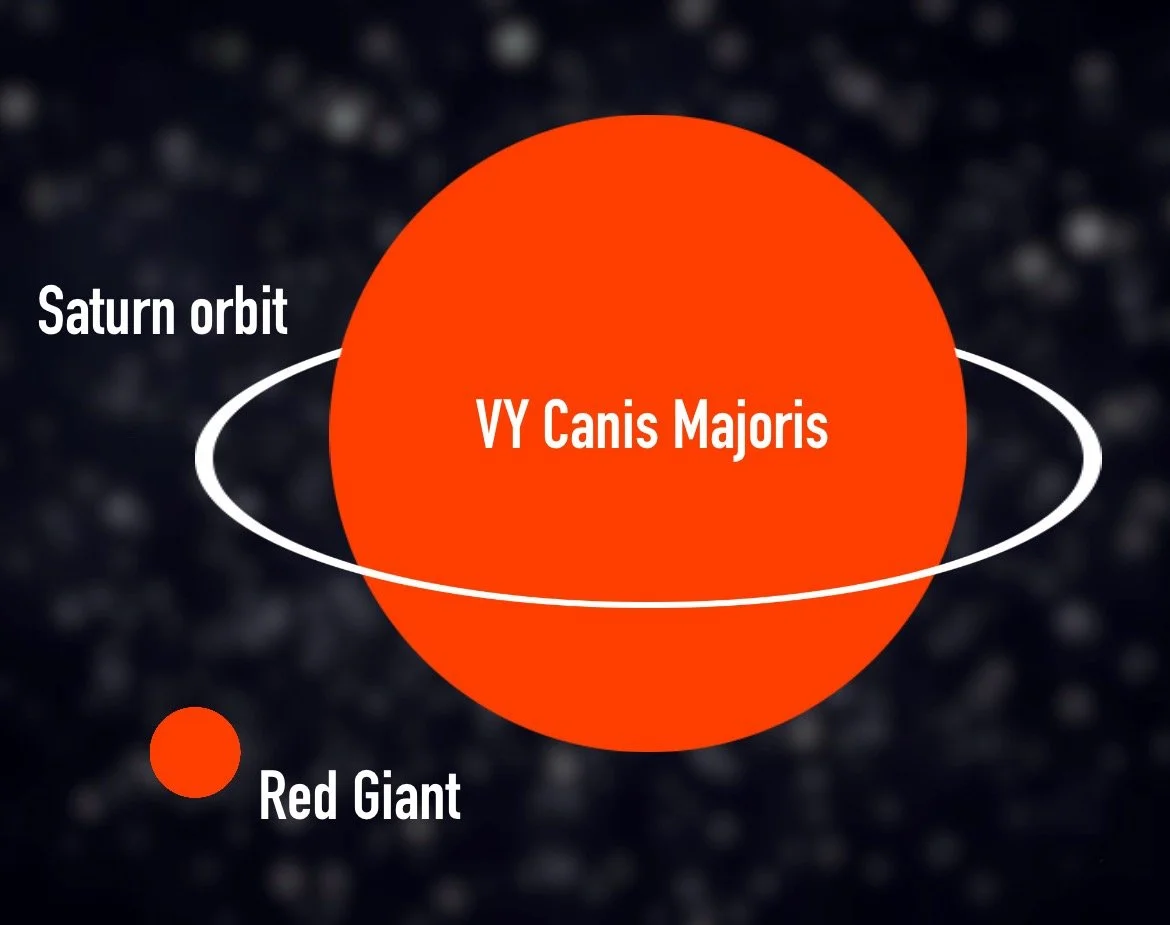

In the upper right are the various giant and supergiant stars. These stars are some of the largest and most luminous in the universe. Red supergiants like Betelgeuse evolve from main sequence stars reaching the end of their life. These tend to have unusually cool temperatures (which makes them red) as the heat is dispersed across a much larger volume. On the other hand, blue supergiants like Rigel maintain very hot temperatures due to their significantly higher mass, often dozens of times the mass of the Sun. Very rare stars like VY Canis Majoris are called hypergiants and have extreme luminosity, mass size and mass loss (due to powerful stellar winds).

In the lower left are the white dwarfs. These small and dim objects are what remains of low mass stars like our Sun after they shed their outer layers upon death and leave behind their dense cores.

Neutron stars and black holes are not plotted on the H-R diagram as they are generally too dim to see with anything but the most massive, specialized telescopes.

YOUNG STELLAR OBJECTS

As we covered earlier in the section on star formation, the gravitational collapse of a molecular cloud forms a protostar. These objects are infant stars that have yet to trigger thermonuclear fusion in their cores and thus have yet to graduate to a fully-fledged star. However, the pressure in their core is still significant enough to radiate thermal energy, causing them to glow. They are usually not as luminous or hot as main sequence stars and are often enshrouded in the dust and gas of their surrounding accretion disks. This is why we usually can’t spot them without the use of powerful infrared telescopes like the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) that can see through the curtains of material that cloak them.

It is common for accreted material falling into the protostar to get swept up by its magnetic field and jettisoned outward from both its poles at supersonic speeds. The resulting jet outflows slam into the surrounding regions of gas, creating ionized shockwaves. These bipolar formations of glowing gas are referred to as Herbig-Haro objects (pictured).

By the time a protostar has accreted nearly all its surrounding material and its stellar wind frees it from its dusty cocoon, it transitions to a pre-main sequence phase. The object is continuing to gravitationally compress and heat up and will soon trigger fusion. They are often characterized by erratic variability in their brightness due to clumps in their protoplanetary disk. T Tauri stars are the low mass version of this, usually having a solar mass less than 2 M☉ and spectral types of M, K, G and F. Their name is derived from the prototype star found at the center of Hind’s Nebula (NGC 1555) in Taurus. Herbig Ae/Be stars are the higher mass version of this, usually having a mass between 2 and 8 M☉ and spectral types of A or B. O-type stars above 8 M☉ are too massive and compress too quickly. By the time they emerge from the surrounding gas and dust, they are already burning hydrogen.

BROWN DWARFS

There’s a common sentiment that goes around saying that Jupiter is a ‘failed star.’ In reality, Jupiter was never really going to become a star as it would’ve needed to be more than 80 times its mass to achieve fusion in its core. It’s more accurate to say that Jupiter is a very successful planet.

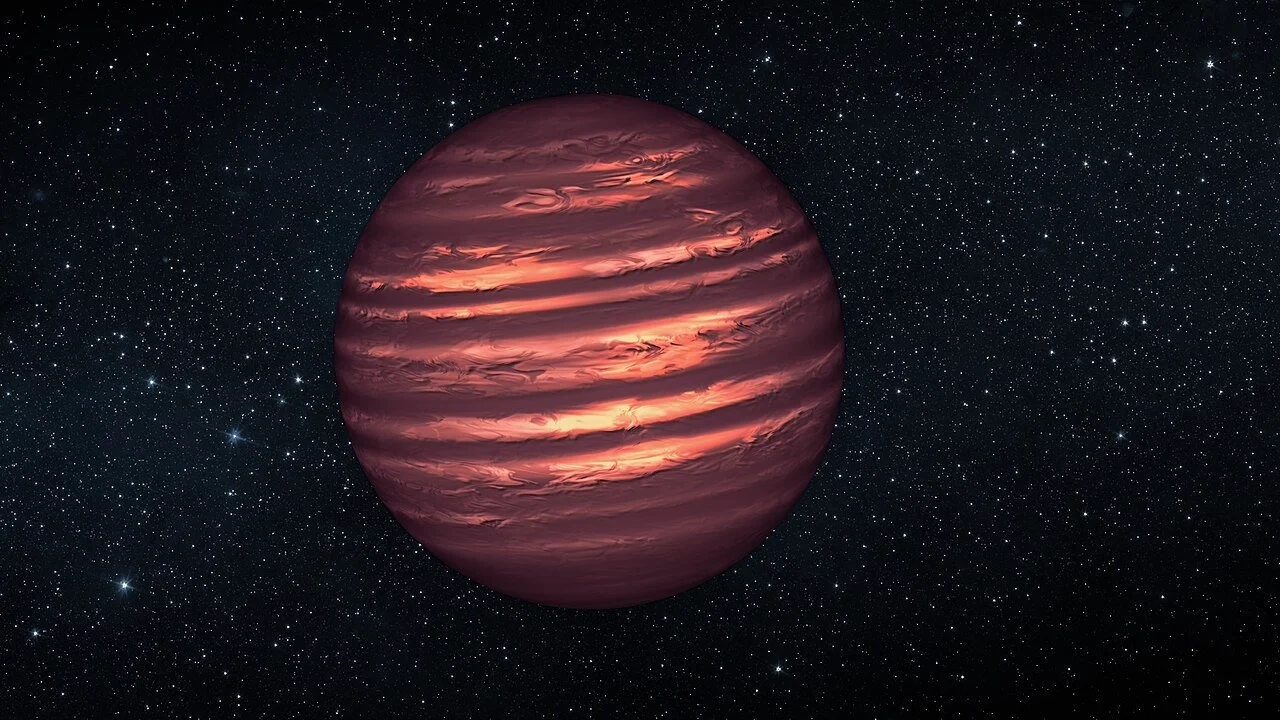

However, there are sub-stellar objects out there that do fit that moniker. They are called brown dwarfs. These are objects larger than the largest planets but smaller than the smallest stars. These are the true failed stars. They form in much the same way fully-fledged stars do but fail to gain enough mass to trigger thermonuclear fusion in their cores, which is what really makes a star what it is.

Brown dwarfs range anywhere between 13 and 80 Jupiter masses (compared to the Sun, which is a whopping 1,048 MJ). They come in different spectral classes like main sequence stars do. L dwarfs are the most massive, followed by T dwarfs and then Y dwarfs are the coolest and least massive. They glow in the red and infrared until they cool down. Brown dwarfs are incredibly difficult to spot. It wasn’t until the late 1980’s that they were confirmed to exist and even as instruments become more advanced, they remain elusive. It’s not impossible, though, as brown dwarfs do emit a subtle glow, not from fusion, but from gravity-induced pressure heating up their interiors. Make no mistake. They may not be true stars, but they are still incredibly massive compared to planets.

MAIN SEQUENCE STARS

The most common type of star in the known universe is a main sequence star. These are stars that have begun the process of thermonuclear fusion in their cores, steadily converting hydrogen into helium. This releases a significant amount of energy and makes them much, much brighter than in their previous protostar phase.

They are also known as dwarf stars to distinguish them from giant stars but this can often be confusing as main sequence stars come in all kinds of sizes. Red dwarf stars are indeed much smaller than red giants but are not to be confused with much smaller white dwarfs, which are not main sequence stars but Earth-sized stellar remnants. On the other hand, the size gap between hotter blue and white main sequence stars and red giants is not quite as wide. In fact, it can be hard to distinguish between the hottest “dwarf” stars and their “giant” counterparts to the point that we must rely on spectral analysis.

What sets different main sequence stars apart largely originates from their mass. As was said in the earlier ‘stellar mass’ section, mass can affect their luminosity, temperature, color, size, internal structure, lifespan, evolutionary path and ultimate fate.

LOW-MASS STARS (RED DWARFS)

The most common type of star in the known universe are red dwarfs. By the broadest definitions, they have a solar mass ranging from .08 M☉ and .8 M☉ (8-80% the mass of the Sun). According to some estimates, red dwarfs make up as much as three-quarters of the stars in the Milky Way. They are also the smallest, coolest and dimmest of the main sequence stars. Because of this, we don’t actually see very many of them in our night sky, despite their frequency. This makes our understanding of their physics limited. The nearest star to our Sun, Proxima Centauri, is a red dwarf that is part of a triple star system that appears prominently in the southern hemisphere during winter nights.

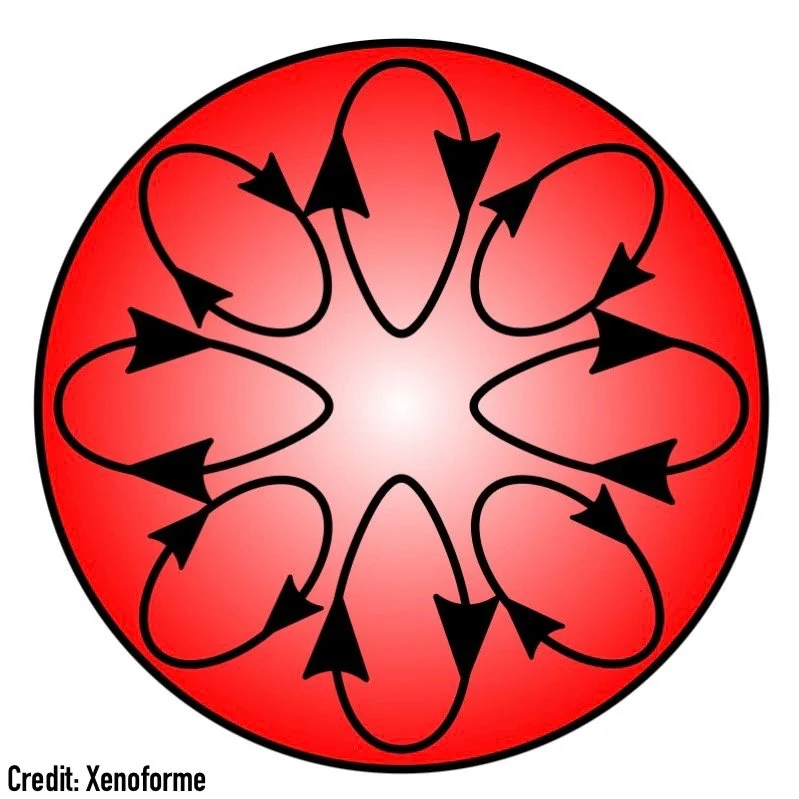

Red dwarfs have less mass and gravity so there is less pressure applied to the star’s core. As a result, red dwarfs fuse hydrogen into helium very slowly and consequently gives the star an extremely long lifespan. The lowest mass red dwarfs are expected to live for possibly trillions of years. The slow burn also results in cooler temperatures. The core reaches 2-3,000,000 K which is enough to sustain fusion, but the surface temperature is only around 2,500-4,000 K, which gives these stars a red or orange color.

The convection zones of the smallest red dwarfs reach all the way to their cores and distribute the helium produced by nuclear fusion throughout the star, preventing helium build-up in the core. This also means that they will ultimately burn all of their hydrogen which also contributes to their long lifespans. Another consequence of their reliance on convection is a very active magnetic field and frequent prominences and intense solar flares. Larger red dwarfs will have a small radiative zone that carries energy through to the convective zone around it.

Remember: M-type stars (and some K-type stars) can be red dwarfs, or they can be red giants or supergiants. The spectral class alludes to temperature and color, not size.

INTERMEDIATE-MASS STARS (SUN-LIKE)

Other stars, like our Sun, are also considered low mass stars but are not red dwarfs. Depending on the purpose, these more massive stars can be put into a subcategory of low-mass stars called intermediate-mass stars. The range of mass for this category is somewhat informal and inconsistent. Some astronomers put it between between .8 M☉ and 8 M☉ (which includes the Sun at 1 M☉) while other astronomers would put the range between 2 M☉ and 8 M☉ (excluding the Sun). For the purposes of this section, we will include the wider range which includes the Sun so as to not leave out any stars.

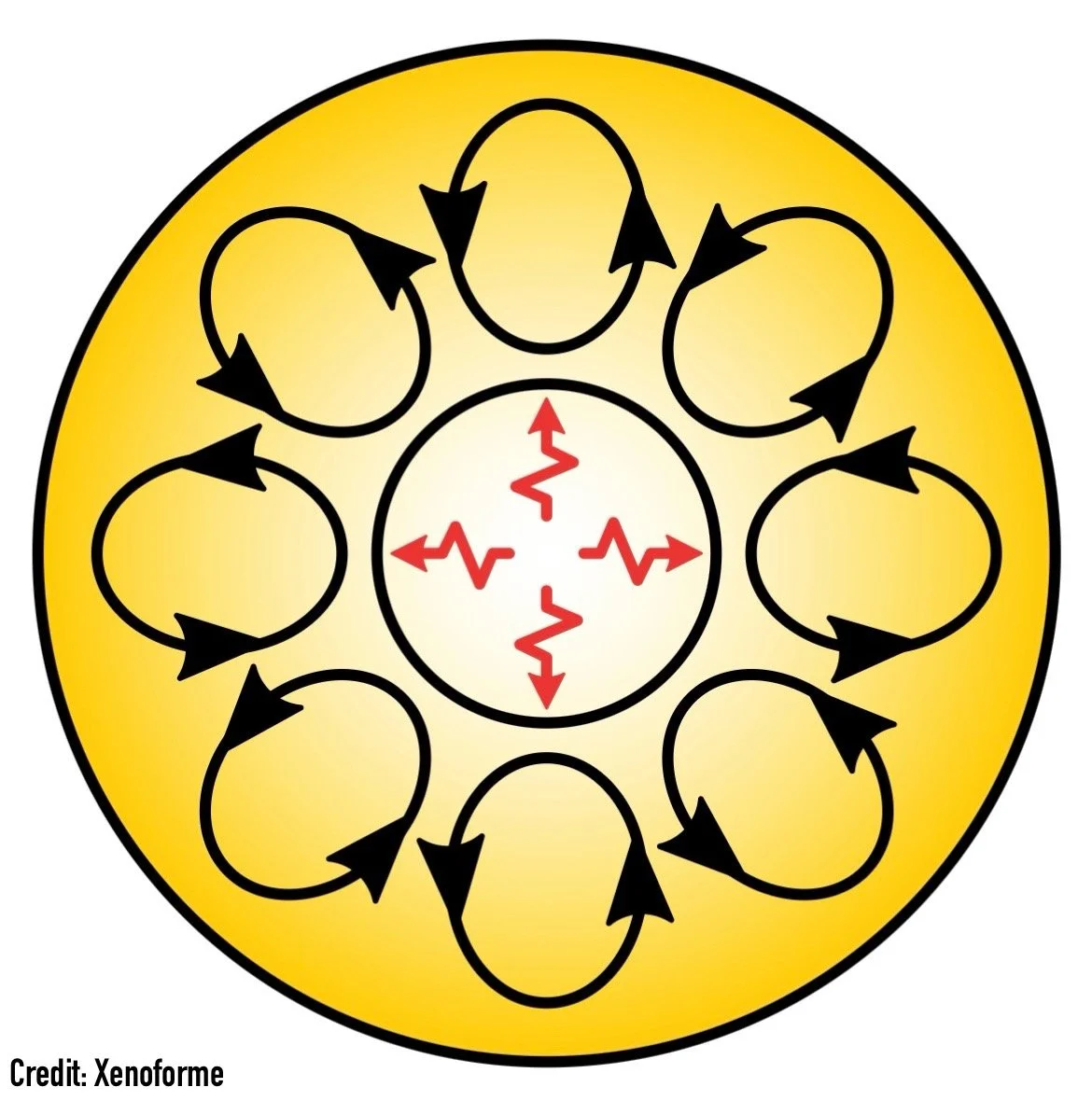

Intermediate stars are much less common than red dwarfs but much more common than high-mass stars. They make up maybe around 10-15% of all main sequence stars. They have bigger, hotter and denser cores. For example, the Sun’s core reaches temperatures of more than 15,000,000 K. The core is surrounded by the radiative zone, the middle layer of the star’s interior. Photons emitted by the core force their way through dense material via radiation and conduction. This can take hundreds of thousands of years. When energy finally escapes the radiative zone, it is cycled through the outermost region of the star’s interior, known as the convection zone. Hotter gas rises towards the star’s surface, then cools and sinks back down. At the surface, these stars range in temperatures between 4,000 and 10,000 K, producing colors from orange to yellow to white.

Because they burn fuel much faster and the core material doesn’t interact with the rest of the star’s material, intermediate stars don’t last nearly as long as red dwarfs. Intermediate mass stars have lifespans anywhere between 50 million and 20 billion years. Stars like our Sun (at 1 M☉) live up to about 10-12 billion years. Stars with double our Sun’s mass, like Sirius A, can burn its fuel within just two billion years. At eight solar masses, a star can burn its fuel in about 100 million years.

HIGH-MASS STARS

High-mass stars generally have a mass greater than 8 M☉. They are some of the rarest, hottest and most luminous stars of the main sequence.

Their incredible mass and gravity create an extreme amount of pressure in their cores and can generate extreme temperatures in excess of 500 million K. In fact, the cores of high-mass stars perform fusion differently. Unlike lower mass stars like our Sun, which simply smash protons together (proton-proton chain), high-mass stars use heavier elements like carbon, nitrogen and oxygen as “helpers” to send the fusion rate into overdrive as the core’s temperature increases (CNO cycle). This is why high-mass stars have significantly shorter lifespans, with some not lasting longer than a few million years. They define “live fast and die young.”

This fusion process also creates a really steep temperature gradient, meaning the temperature at the very center of the star is much, much higher than the regions around it. This enables a convection zone as the primary source of heat transportation around the core while the outer layer of the star allows energy to pass through more smoothly, the radiative zone. Interestingly, this is the reverse of how intermediate star interiors are structured.

At the surface, these stars reach temperatures greater than 10,000 K, with some of the hottest known stars reaching an absolutely scorching 200,000 K. These extreme temperatures are what give O and B-type stars their white and bluish colors.

GIANT STARS

Main sequence stars come in a wide range of sizes, so you’ll be forgiven for thinking some of them are considered giant stars. In truth, even the largest are still categorized as dwarf stars. This is to distinguish them from the true giants.

Stars spend most of their life on the main sequence, steadily fusing hydrogen into helium. This generates the outward energy that pushes against the inward gravity, a delicate balance that holds the star together. What happens when hydrogen runs out and that balance begins to falter? This sets the stage for a dramatic transformation that marks the beginning of the end. What happens inside a star at this point is complex, but we’ll keep it simple.

RED GIANT STAR

Let’s look at what happens in an intermediate-mass star first. As hydrogen fusion in the core slows, outward pressure weakens and gravity begins to dominate. The core contracts and heats up. The increased temperature is not hot enough to trigger fusion in the inert helium core but is hot enough to trigger fusion in the hydrogen shell surrounding it. In fact, the hydrogen here burns faster than it previously did in the main sequence, while continuing to dump the resulting helium into the core. This faster fusion generates more energy to push back against gravity. The star begins to swell, entering the sub-giant phase.

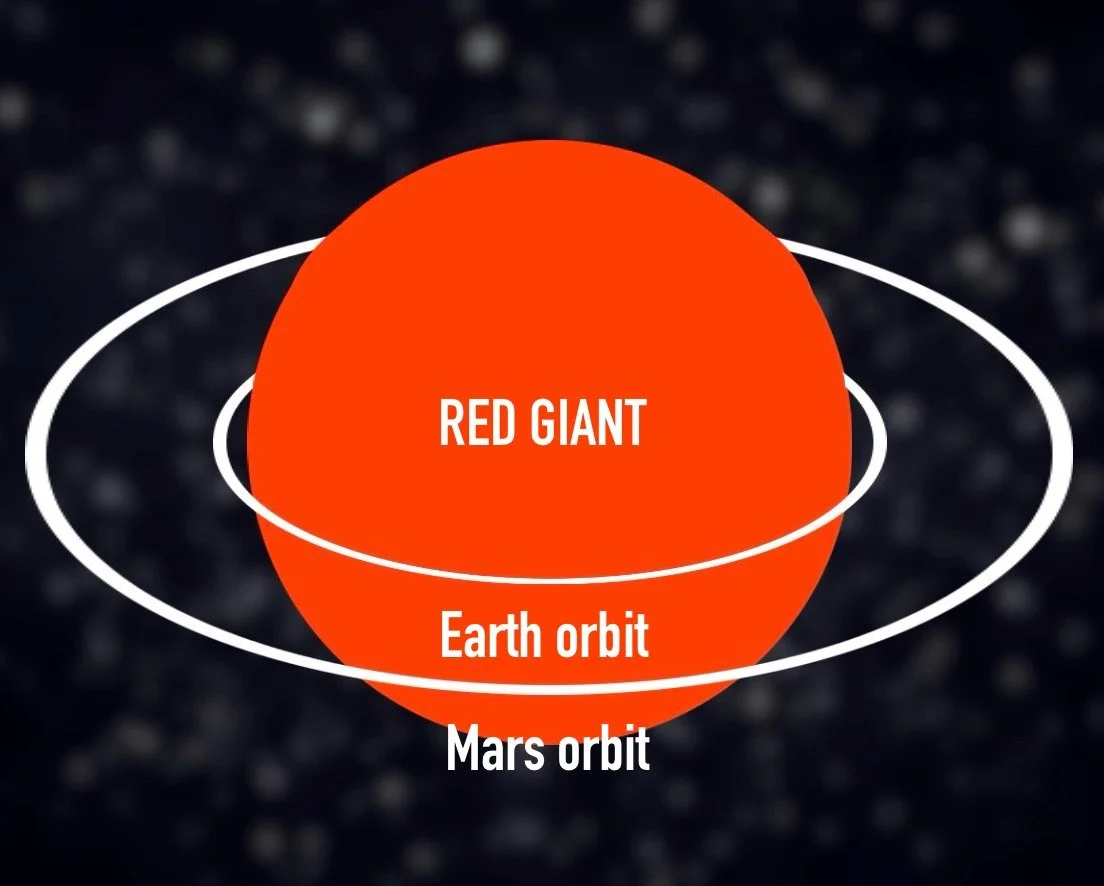

The expansion is modest at first, but as hydrogen burning intensifies and the core compresses, the star’s expansion accelerates. Its surface reaches further and further out, growing a few hundred times their original size across the span of a few billion years. With star’s heat being spread across a larger and larger volume, the star cools, taking on a red hue. The star has become a red giant. In this stage, the core is highly compressed, the outer layers are diffuse, and the star’s luminosity can soar thousands of times above its main sequence brightness. The star will shed about a third of its mass carried away by its powerful stellar winds. Eventually, the core contracts so much that it becomes hot enough to trigger helium fusion. This is where things start to go bad quickly, but we will come back to that soon.

Note: Red dwarf stars are not massive enough to enable this process to become giant stars. They go through a different process which we will cover soon.

SUPERGIANT & HYPERGIANT STARS

When high-mass stars undergo this late-stage evolution, their incredible gravity compresses their cores to even more extreme temperatures and fusing increasingly heavier elements. This process begins in the core and then unfolds outward in a series of concentric shells. First, hydrogen fuses in the core, then in a surrounding shell once core hydrogen is depleted. Helium fusion then ignites in the core, with hydrogen fusion continuing in an outer shell. As the cycle progresses, the core begins fusing carbon, while layers above it sequentially fuse lighter elements. This layered burning structure builds up until the star develops an iron core at its center, surrounded by up to six shells, each fusing a progressively lighter element than the one beneath it.

The energy generated creates far greater outward pressure, expanding the star beyond the radius of a giant star. They become supergiants, or even hypergiants. These profoundly large and luminous stars can reach sizes hundreds to well over a thousand times the diameter of the Sun. They often do cool and turn red as well but will sometimes return to a blazing blue color as they contract and expand across this tumultuous process.

One of the largest known stars is VY Canis Majoris. Its diameter is estimated to be 1,420 times that of the Sun. If it were placed at the center of our solar system, its surface would reach 70% of the way to Saturn’s orbit.

MULTI-STAR SYSTEMS

In our solar system, the Sun looms ever present and unchallenged as the sole dominating celestial object. However, this is not the case in many star systems. In fact, most star systems that we know of have at least two or more stars!

It is estimated that perhaps up to 85% of stars are in binary systems. A binary system is simply one in which two stars are gravitationally bound and orbit around their common center of mass, known as the barycenter. As you may remember from the gravity primer, the more massive a star is than the other, the closer the barycenter lies to it. The time it takes them to orbit each other can vary wildly, from a matter of hours (close orbit) to thousands of years (wide orbit).

There are four types of binary systems:

Visual binaries are simply a pair of stars that can be seen separately through a telescope. Examples: Aberio, Sirius

Spectroscopic binaries appear as one point of light, but their spectral lines shift back and forth due to the Doppler effect as the two stars orbit each other. Ex: Mizar, Spica

Eclipsing binaries are stars that pass in front of each other from Earth’s perspective, causing dips in their brightness. Ex: Algol, Sheliak

Astrometric binaries are seen as one visible star with a “wobbling” motion that betrays an unseen companion, usually because it is too small and dim. Ex: Procyon, Barnard’s Star

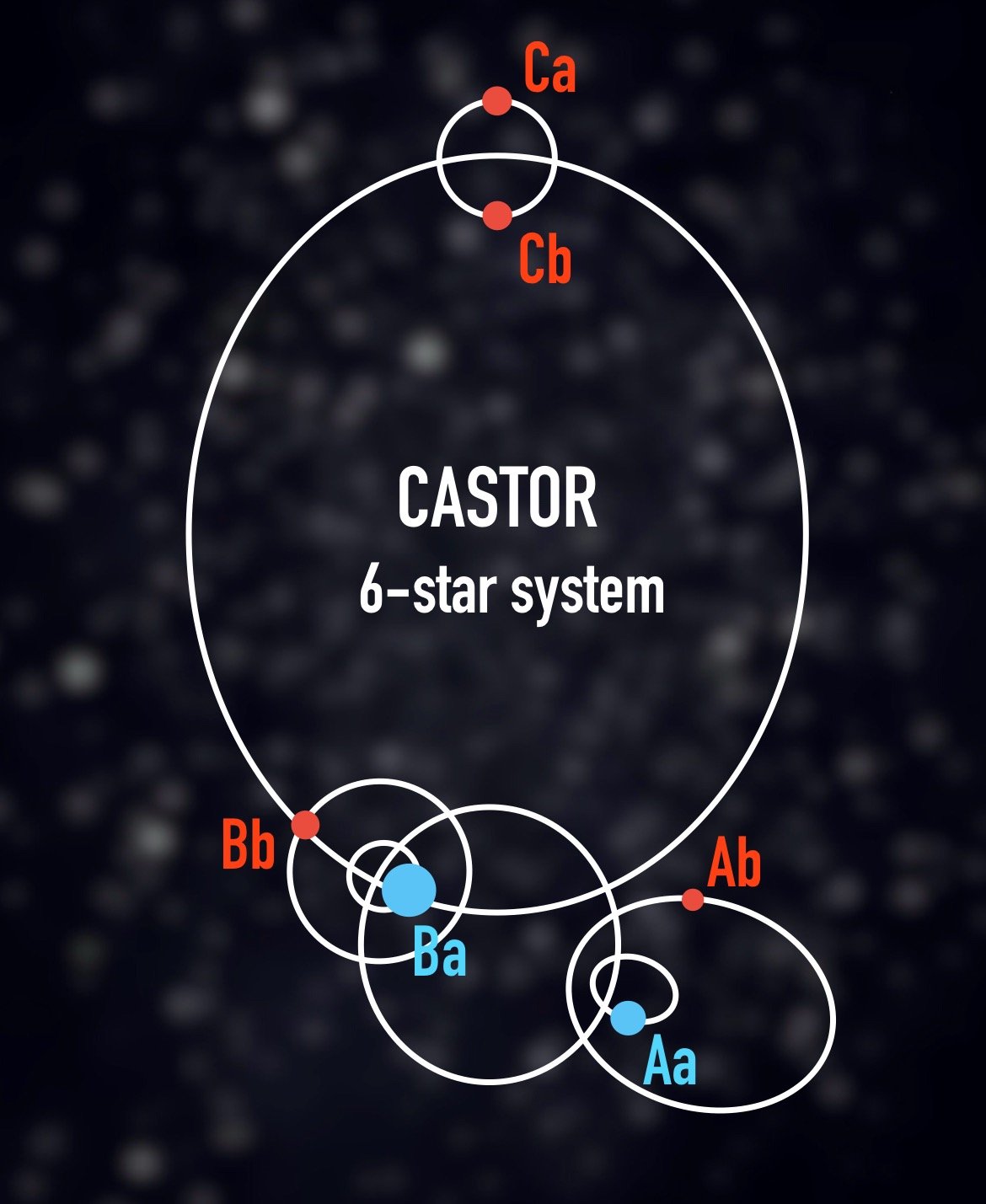

The universe doesn’t stop at simple binaries! There are star systems that are far more intricate, hosting three or more. Triple star systems often have two stars orbiting each other closely while a third star orbits at a greater distance. There are quadruple star systems and higher that consist of multiple binary pairs twirling around each other in a complex ballet choreographed by gravity. Some have even been found to cause binary pairs to exchange partners, fling one another into distant orbits or even eject a member entirely.

Fun fact: There are only two known star systems that consist of seven stars: AR Cassiopeiae and Nu Scorpii.

While multi-star systems are common, many astronomers speculate whether they are too chaotic to harbor habitable worlds. The gravitational pull of multiple stars swinging around can destabilize planetary orbits and even hurl them out into interstellar space. Their shifting proximity can fluctuate a planet’s climate between extremely cold and extremely hot, preventing a consistent environment for life to flourish.

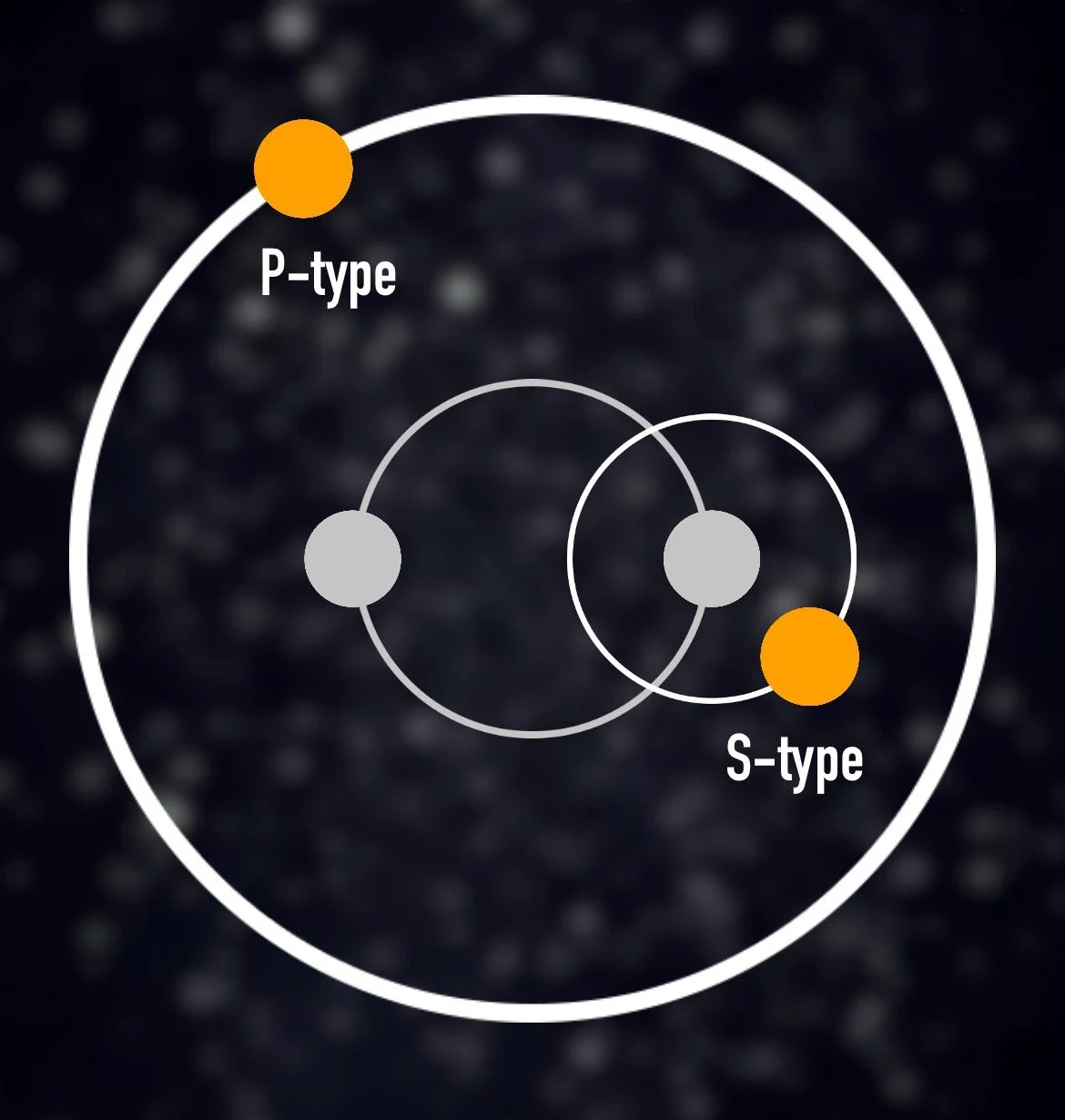

There are two configurations that have been found to work for stable planetary orbits in multi-star systems:

S-type orbits have a planet orbiting one star in a system while the other star orbits at a greater distance.

P-type orbits have a planet orbiting around both stars as if they were a single gravitational source. This is what Tatooine does in Star Wars!

VARIABLE STARS

Variable stars are stars whose apparent brightness as seen from Earth changes over time. There are a variety of things that can be responsible for this.

Astronomers can determine which cause is responsible by observing their light curve and their spectra. A light curve is simply a graph that shows how the brightness of an object changes over time. Different types of variables will present recognizable patterns in their light curve that astronomers can identify. The star’s spectra, the presence and absence of different wavelengths of light, can reveal ways in which stars are moving via the Doppler effect. (learn more about this in the light section). Over 100,000 variable stars have been catalogued. Variables fall under one of two main categories: intrinsic variables and extrinsic variables.

INTRINSIC VARIABLES

Intrinsic variables are stars which themselves change in brightness due to internal processes.

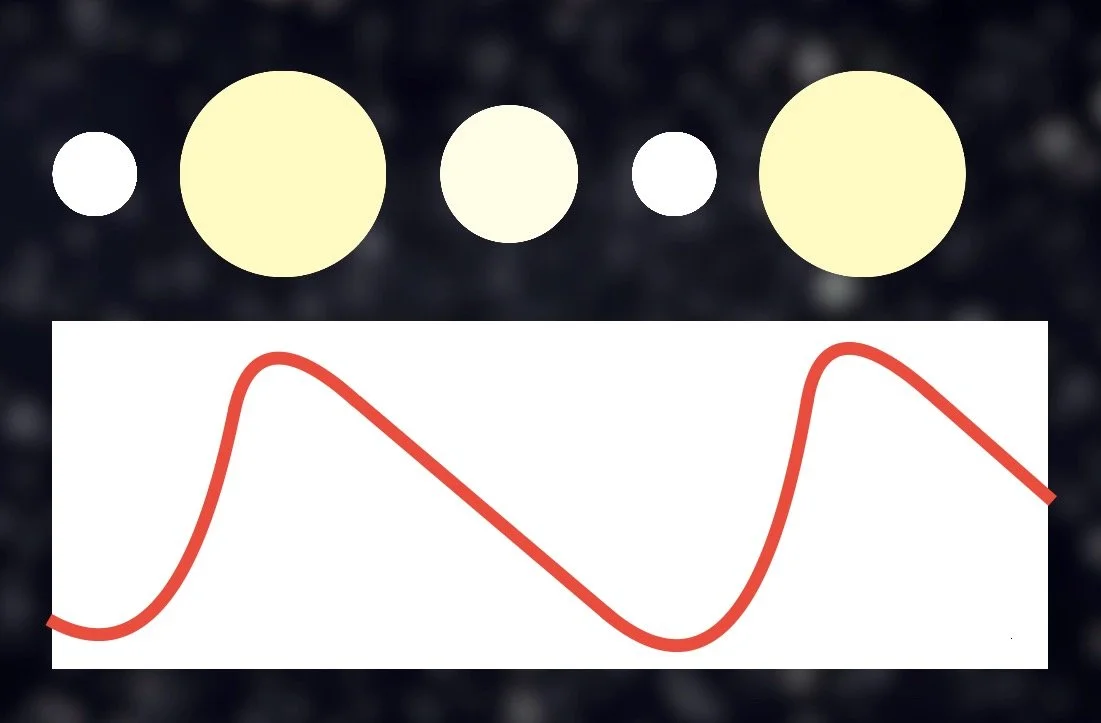

Pulsating variables are stars that expand and contract periodically, changing their intrinsic luminosity. Outer layers of helium become partially ionized, making them opaquer and trapping heat inside the star. This increases thermal pressure which pushes the layers outward, cooling the star. As the star cools, it contracts again. This is called the kappa-mechanism. Different types of pulsating stars exhibit characteristic periods, amplitudes, and evolutionary stages:

Cepheid variables: Pronounced “see-fee-id.” Large, massive stars with long, regular pulsation periods; their brightness is strongly linked to the pulsation period (more on this later).

RR Lyrae variables: Small, old stars with short, rapid pulsations and nearly uniform brightness, unlike Cepheids.

Mira variables: Aging red giants with very long periods and huge brightness swings, far more dramatic than Cepheids or RR Lyrae. Named after the first modern variable star identified.

Delta Scuti variables: Small, relatively hot stars with very short, low-amplitude pulsations, much faster and subtler than the others.

Eruptive variables are stars that change in brightness irregularly due to either material being lost from the star or material being accreted to it. These changes can result from stellar flares, mass loss, accretion from a companion, or sudden instabilities in the star’s outer layers.

Explosive variables are stars that brighten because of sudden, powerful bursts of energy generated by thermonuclear processes. The most dramatic example of this would be supernovae, the explosive death of a high-mass star. Another would be binary star systems where a white dwarf accretes material from a companion star. This buildup can trigger a thermonuclear explosion on the white dwarf’s surface.

EXTRINSIC VARIABLES

Extrinsic variables are stars that change in brightness due to external reasons, not changes in the star itself.

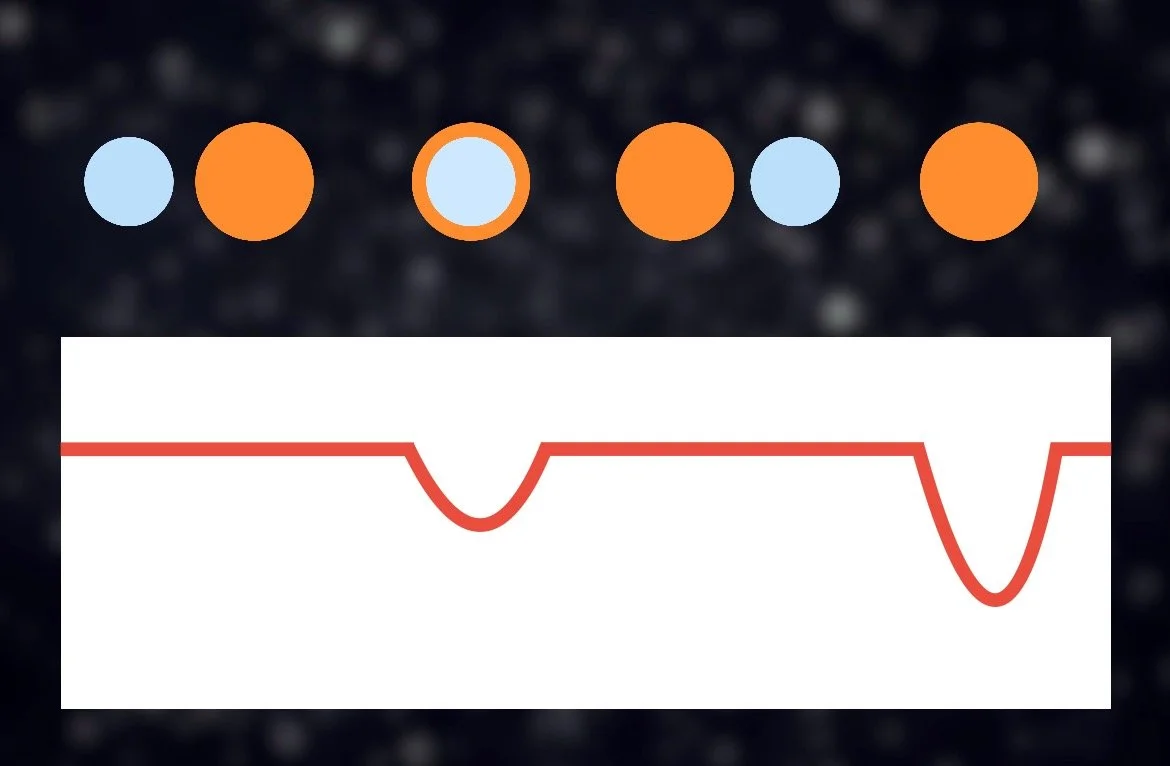

Eclipsing binaries are stars in which brightness dips when one star passes in front of the other. The shape of the light curve can tell us much about the stars. Time between dips can tell us their orbital period. The depth and width of the dip can tell us about the stars’ sizes, temperatures and orbital inclines. When the brighter star is blocked, there is a deeper dip, while blocking the dimmer star results in a shallower dip.

An alternative version of this is transiting exoplanet systems. These are stars that have their own planets orbiting them. If the exoplanet passes in front of the star, the light curve will show a slight dip, then an even slighter dip when the exoplanet passes behind the star. The depth, width and timing of the dip can tell us much about the nature of the planet.

Rotating variables are stars in which brightness changes due to their rotation and surface features. This would be things like starspots or uneven brightness. The variation is periodic, matching the star’s rotation speed.

Microlensing variables are stars whose brightness changes when a massive object passes between them and Earth, causing a gravitational lensing effect. This warping of spacetime bends and sometimes even magnifies light passing through, making very distant stars appear brighter than they otherwise would. These are rare and usually temporary but predictable.

STAR DEATH

When main sequence stars exhaust their hydrogen and cease fusion in their cores, a complex chain of internal processes begins that results in the continuous compression of the core and the significant expansion of the outer layers. As we know, this is when the star leaves the main sequence and becomes a giant star, or if the star is especially massive, a supergiant or hypergiant. Stars can remain in this state for quite a while, contracting and expanding as their cores heat up and begin fusing heavier elements. What ultimately happens from here ultimately depends on their mass.

RED DWARFS

Stars at the lowest end of the mass range, such as red dwarfs, are believed to have lifespans that far exceed the current age of the universe. Therefore, it is not believed that any have yet to die. However, scientists speculate that they are not capable triggering fusion beyond hydrogen and thus skip the giant star phase. Instead, it is predicted that they simply increase in surface temperature as they generate more radiation across their lifespan. They may change colors from red to yellow to possibly even bluish white. Astronomers dub this speculative phase, the blue dwarf phase.

SUN-LIKE

Of course, more intermediate-mass stars like our Sun do become giant stars. This is a consequence of increased energy generated by hydrogen and helium in the core and concentric shells surrounding it. The intensifying radiation pushes the outer layers of the star outward. Eventually, helium fusion produces a core of carbon and oxygen, which the star is unable to fuse further. Hydrogen and helium fusion continue in the surrounding shells, causing the star to develop an unstable, pulsating behavior. The strong stellar winds gradually blow off gas from the star’s surface out into interstellar space.

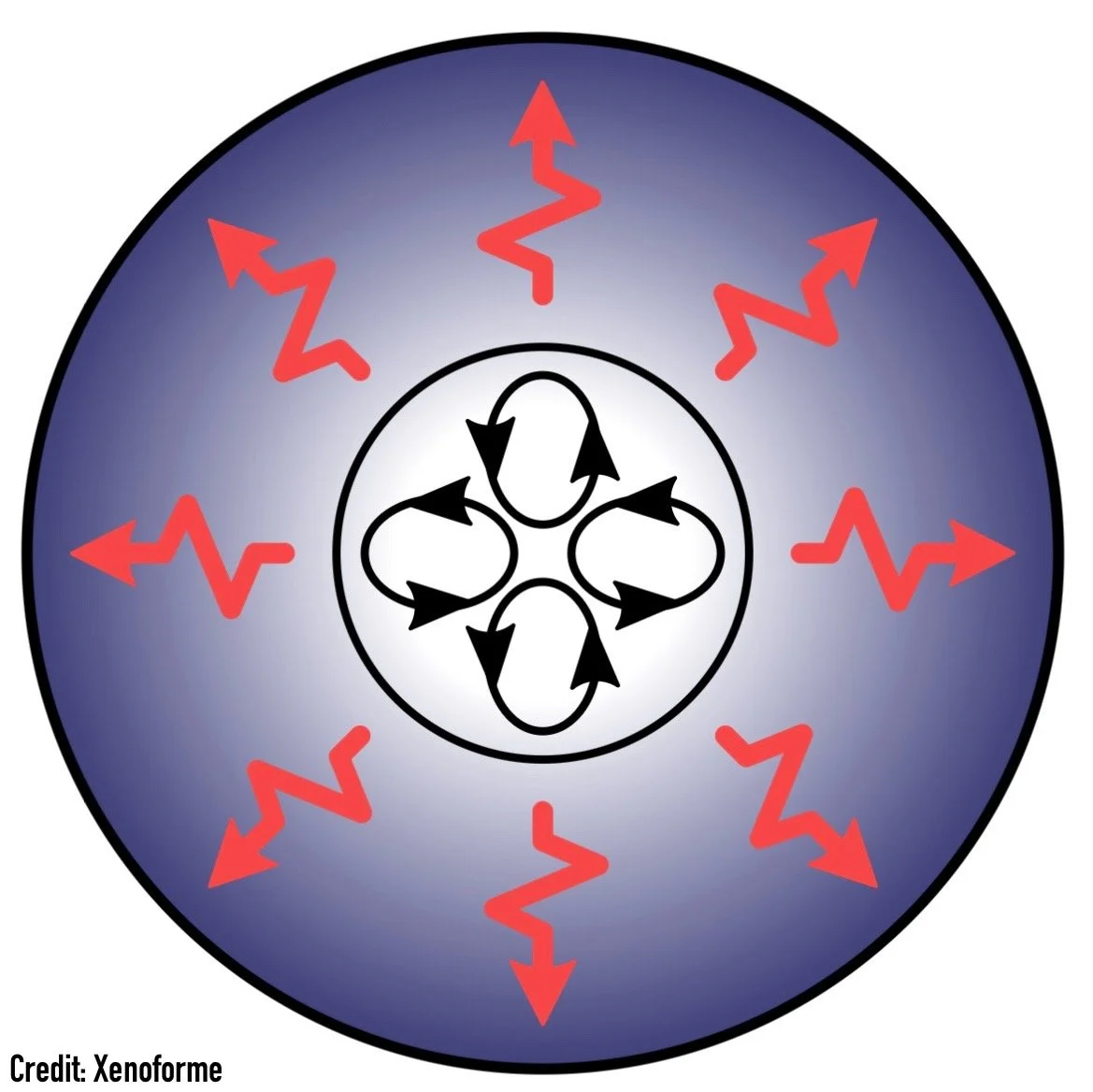

PLANETARY NEBULAE

Once enough of the star’s outer layers are shed, the hot carbon-oxygen core becomes exposed, and its powerful ultraviolet radiation is unleashed. This blistering energy ionizes all of the surrounding shells of gas that were shed, causing them to glow. This becomes what is known as a planetary nebula. These are remarkably beautiful and sometimes complex in structure, especially in multi-star systems where obstructing companion stars can heavily influence their dispersal. While they range in shape and size, they are generally rounded and roughly one light year across. On an astronomical timescale, planetary nebulae last very briefly, no more than tens of thousands of years, before dissipating into the interstellar medium.

The first of their kind ever discovered was the Dumbbell Nebula (M27) by famous French astronomer Charles Messier. German-British astronomer Willam Herschel would coin their name in reference to their often rounded, planet-like appearance. Pictured is the relatively large Helix Nebula, sometimes referred to as the Eye of God. It is located 700 light years away in Aquarius.

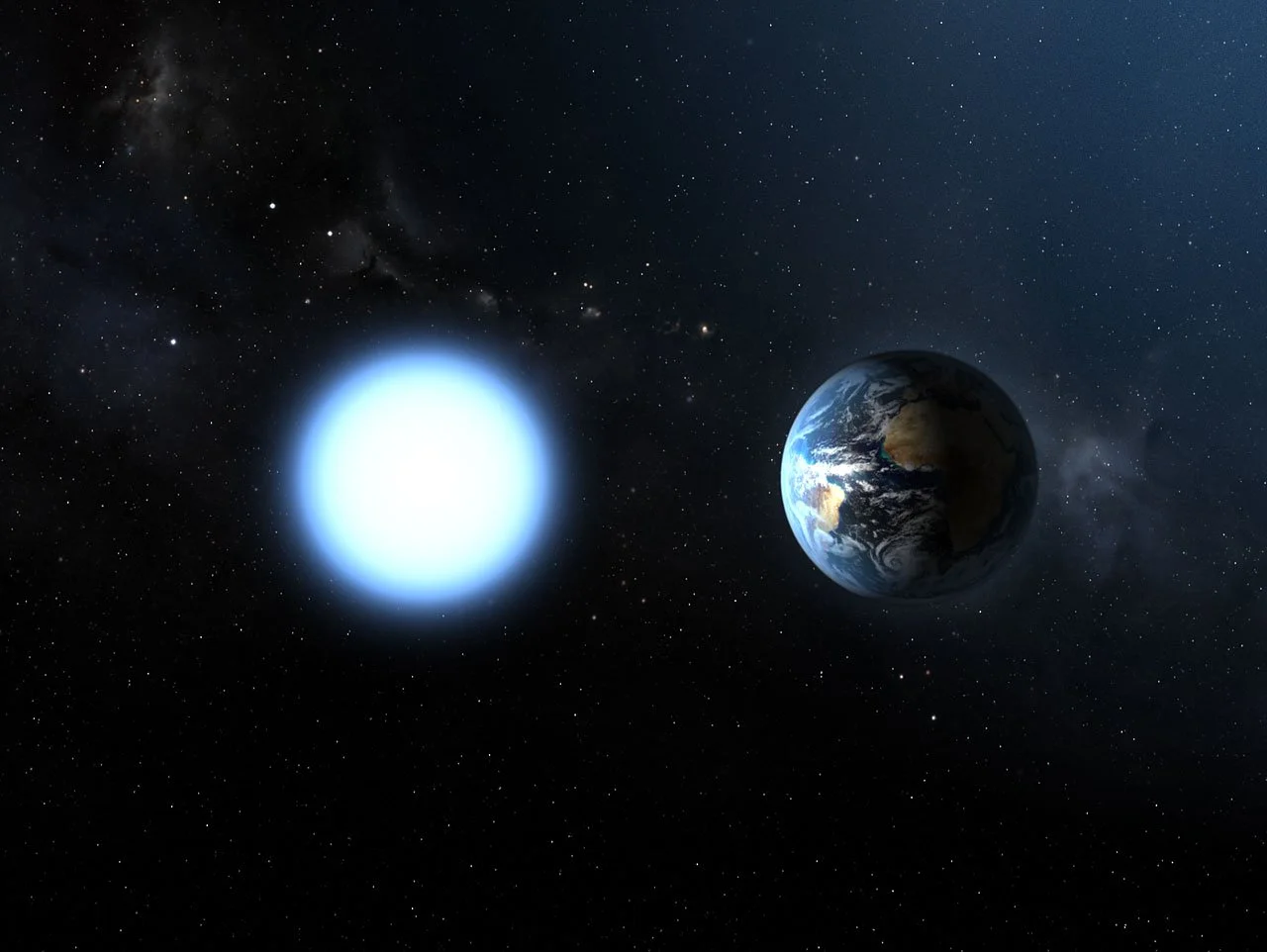

WHITE DWARFS

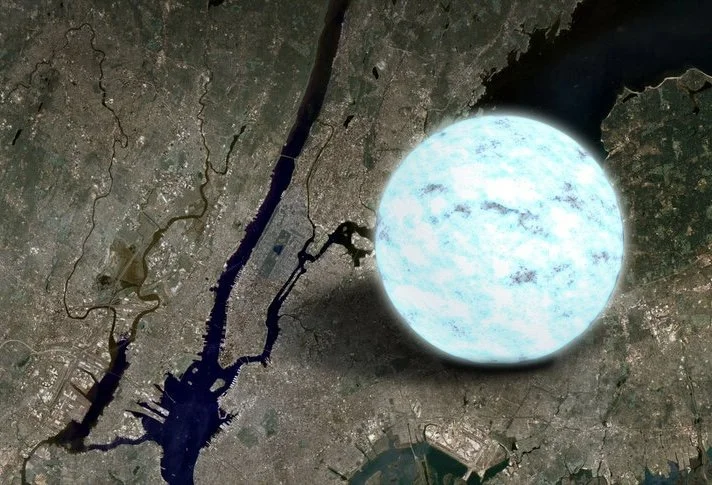

At the center of the planetary nebula is the dead star’s remnant core in the form of a white dwarf. No larger than Earth and no longer engaged in thermonuclear fusion, this dense sphere of carbon and oxygen avoids gravitational collapse only through electron degeneracy pressure. White dwarfs have immense gravity that tries to crush them, packing their atoms tightly together. According to the Pauli Exclusion Principle, crammed-together electrons do not like to occupy the same quantum states at the same time, so some have to increase their energy level. This creates an opposing pressure that acts against gravity and holds the stellar remnant together. Also, due to the lack of fusion, white dwarfs glow through residual heat alone. Most white dwarfs have been observed with surface temperatures between 8,000 and 40,000 K. Over billions of years, they are expected to gradually radiate their heat away, becoming cooler, redder and dimmer. They ultimately will leave behind a dark husk known as a black dwarf. Just like with red dwarfs, however, this is speculative due to the vast time duration necessary.

The second white dwarf ever discovered is also the nearest to us, located in the Sirius binary system just 8 light years away in Canis Major. However, at almost 9th-magnitude, it’s very dim alongside its much larger and brighter white-blue companion star.

About 97% of all main sequence stars will end their lives as a white dwarf.

HIGH-MASS STARS

As was laid out previously, the evolution of high-mass stars into supergiants and hypergiants is a more complex process. Where low-mass stars never engage in fusion beyond that of helium, high-mass stars fuse heavier elements. By the time their cores have fused all their silicon into iron, this is the end of the line. The nuclei of iron atoms are incredibly tightly bound to the point that trying to fuse them would actually consume energy rather than release it. Fusion can no longer persist beyond iron. As concentric shells fuse heavier and heavier elements, their byproducts sink down to the core like “ash.” The core grows, but without energy generated by fusion to support it.

What happens next is what makes high-mass stars so exciting. Where low-mass stars like red dwarfs and Sun-like stars go out with a whimper, high-mass stars go out with a bang. A really big bang (not that one).

SUPERNOVAE

Once the growing iron core reaches a certain mass threshold, known as the Chandrasekhar limit, it buckles under its own weight. The core collapses in a fraction of a second until nuclear forces halt it, creating a terrifying rebound. Like slamming a basketball into the floor, the outer layers crashing crash inward, hit the rebounding core and are blasted outward. Known as a supernova, the star explodes in a blinding flash, brighter than billions to trillions of Suns, capable of outshining an entire galaxy. These are some of the most powerful events in the known universe.

The explosion is not only powered by the rebound effect. When the core collapses, it crushes atoms together with such force that protons in the nuclei combine with electrons to create neutrons via the weak nuclear force. This also releases a torrent of countless neutrinos. These ghostly, near-massless particles carry away an enormous amount of energy, pushing the outer layers outward in a powerful shockwave.

Another byproduct of the core collapse is the collision of free neutrons with iron and other heavy nuclei. This rapidly creates unstable, neutron-rich atoms that decay into heavier elements like gold, uranium and platinum.

SUPERNOVA REMNANT

After the brightness of the explosion subsides, an expanding gaseous shell remains, slamming into and sweeping through the surrounding interstellar medium at supersonic speeds. Known as a supernova remnant, this colossal cloud often features an intricate network of bubbles and filaments formed by turbulence, magnetic fields and the uneven distribution of gas and dust in the surrounding regions. Though not unlike planetary nebulae, these are enriched in heavier elements and radiate in higher energy wavelengths like ultraviolet, x-rays and sometimes even gamma rays.

Pictured is the first entry in Charles Messier’s famous catalogue, the Crab Nebula (M1). Located 6,500 light years away in Taurus, this was left behind after a supernova that occurred in 1054 AD. The brilliant light of the supernova was visible in the daytime for three weeks and visible at night for two years.

NEUTRON STARS

If a star with a mass roughly between 8 and 20 M☉ goes supernova, the collapse of the core is forceful enough to overcome the electron degeneracy pressure that normally holds white dwarfs together. However, under this crushing force, the protons and electrons in atoms are smashed together to form neutrons. The core becomes a neutron star. Because neutrons are much heavier particles than electrons, neutron degeneracy pressure is able to halt the collapse.

Neutron stars have a mass that exceeds that of the Sun compressed down to about the size of a large city. One teaspoon of material would weigh more than Mount Everest. Suffice it to say, these are extremely dense objects. To become so compact causes the rotation of the star to speed up significantly in order to conserve angular momentum. Neutron stars can spin dozens to hundreds of times in a single second! They are also extremely hot. Their surface temperatures can exceed 10 million K when they are newly formed. However, just like white dwarfs, they do cool down over time.

These objects are already some of the most exotic and interesting objects found in space, but there are some neutron stars that exhibit some extra peculiar behaviors.

For example, some rapidly rotating neutron stars emit beams of electromagnetic radiation from their magnetic poles. Because these poles can become misaligned from the axis of rotation, the beams sweep through space like a lighthouse. If the beams cross Earth, we can detect them as regular pulses of various light (though radio waves are most common). We call these pulsars.

There are other neutron stars that have incredibly strong magnetic fields, often 1,000 times stronger than typical neutron stars and trillions of times stronger than Earth’s. They are called magnetars. They emit intense X-rays and gamma rays. They can produce powerful flares that release as much energy as the Sun emits in 100,000 years. They have even been observed to experience starquakes. They are valuable to physicists by providing the opportunity to study extreme magnetic environments.

BLACK HOLES

If a star with a mass that exceeds 20 M☉ goes supernova, the collapse of the core is so forceful, not even neutron degeneracy pressure can resist it. In fact, at this point, there is no known force that can stop the star’s immense gravity from crushing matter down to a point of infinite density and zero volume. This point, known as a singularity, gravitationally warps the spacetime around it so extremely that not even light can escape. Thus, the singularity becomes enshrouded by a sphere of absolute darkness, known as the event horizon. The collapsed core has become a stellar mass black hole.

Note: It should be emphasized that the name is only meant to reference the void-like appearance of black holes. In reality, they are physical objects surrounded by warped spacetime.

Black holes themselves do not emit any light so they can’t be observed directly. Instead, we must look for their effects on their surroundings. In desolate regions, astronomers might find stars suspiciously revolving around empty space and use their orbital trajectories to calculate the hidden object’s mass. There are rare occurrences in which gas and dust will swirl around a black hole, forming a superheated accretion disk. These resemble planetary rings like the ones found around Saturn, but they have an intense glow caused by friction as matter spirals inward. Remarkably, the disk often appears to wrap around the event horizon even when viewed edge-on. This illusion is created by the black hole’s spacetime-warping gravity, which bends the light from the far side of the disk around the black hole. This effect is called gravitational lensing. This also affects any light passing close by from distant background objects, causing them to appear distorted, or even magnified.

MEASURING BRIGHTNESS

An important part of studying stars is determining their brightness. This reveals much about the star from its mass, temperature and even its distance. There are three ways in which we measure a star’s brightness: luminosity, apparent magnitude and absolute magnitude. Let’s go over what each of these mean and how they relate to each other.

LUMINOSITY

Luminosity is the measure of a star’s intrinsic brightness. This does not depend on distance. It’s how bright the star really is.

We quantify this in a few different ways. The more technical way is to measure the total amount of energy the star emits per second, usually measured in watts (W). This number is usually really, really large with many digits. A simpler way we communicate this is by comparing a star’s output to the Sun, using the solar luminosity unit (L☉). For example, Sirius has a luminosity of about 25 L☉, meaning it is about 25 times brighter than the Sun.

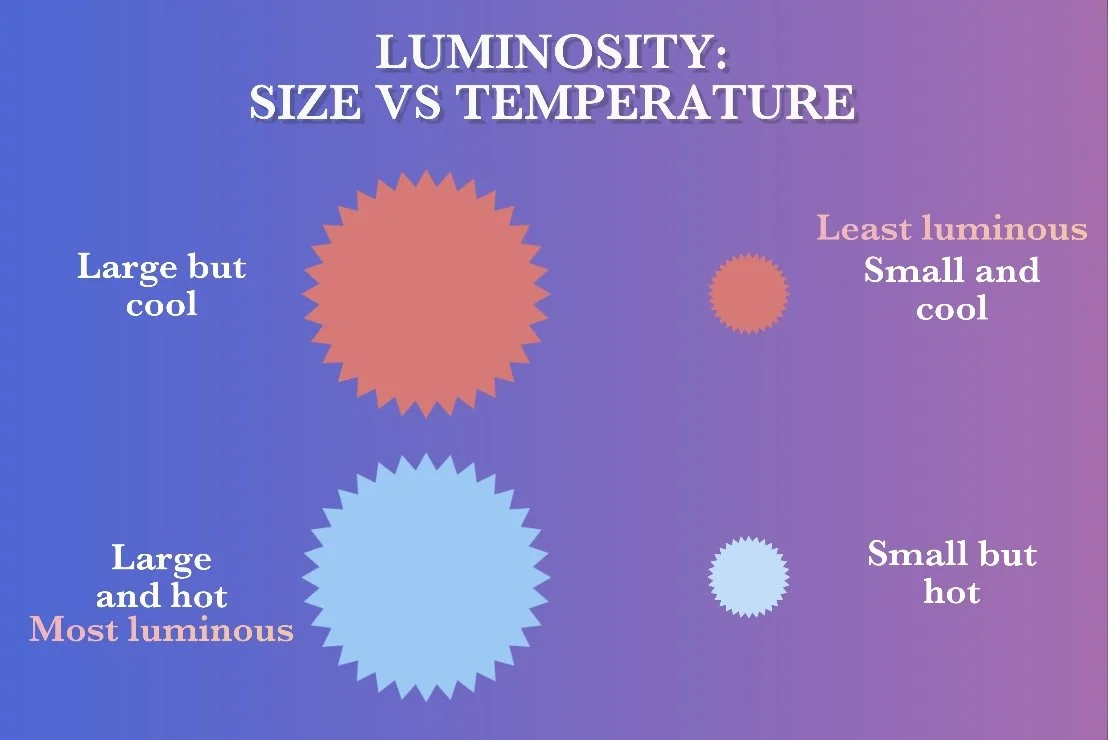

How much energy a star emits is primarily determined by its mass as it determines how much gravity compresses the core to trigger fusion. However, the visible characteristics that define a star’s luminosity are the star’s size and temperature.

According to the Stefan-Boltzmann law, the luminosity of a star is proportional to its surface area and proportional to the fourth power of its surface temperature. This means the bigger and hotter a star is, the brighter it shines! Doubling the radius of a star quadruples its luminosity. Doubling the surface temperature increases luminosity sixteen-fold. So, between the two factors, temperature is much more dominant. That being said, size still matters. The luminosity of a star expanding into a red supergiant can overpower the temperature of a hot, blue star.

THE MAGNITUDE SCALE

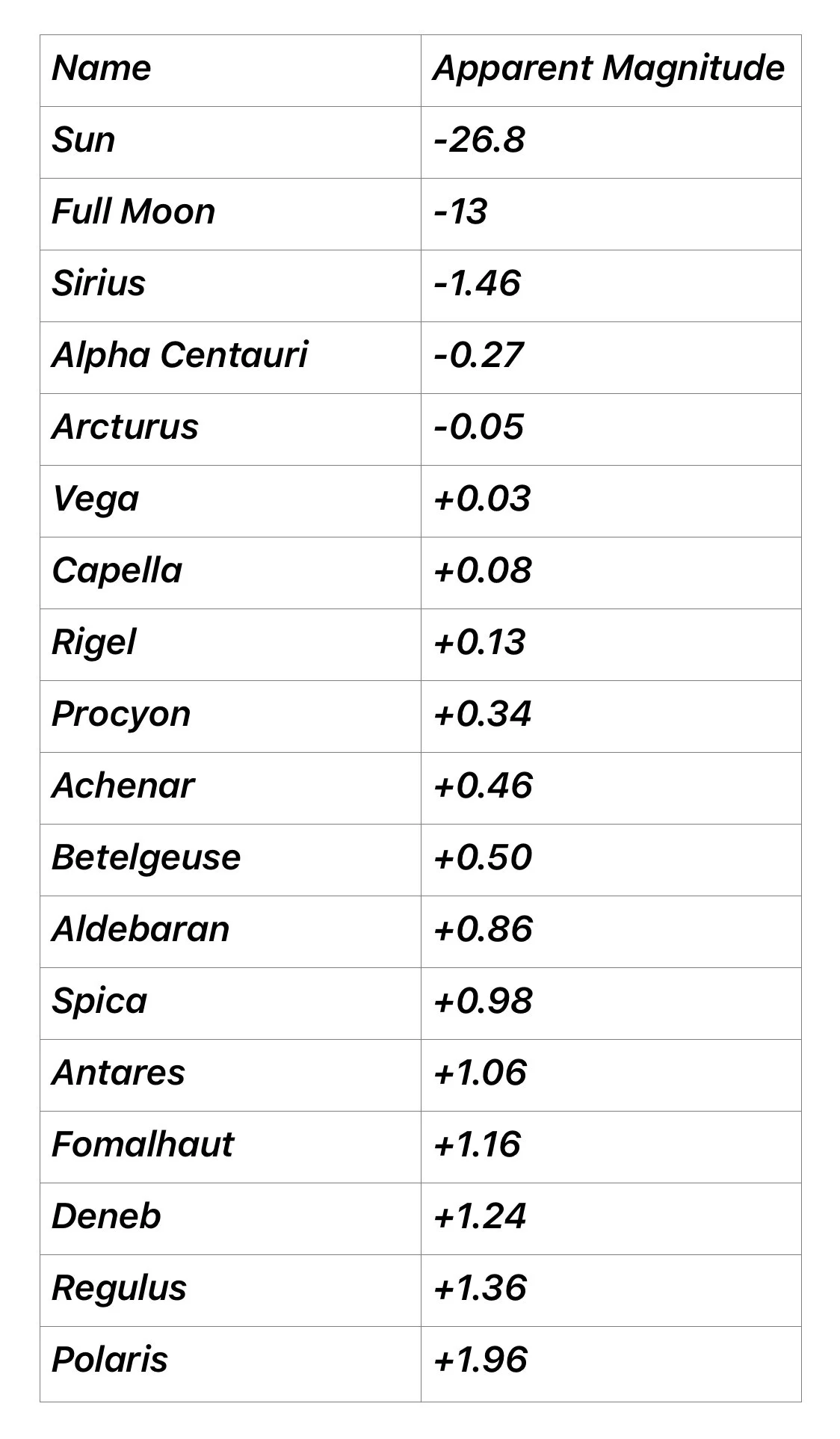

Before we get to apparent and absolute magnitude, we first need to go over what magnitude is. The magnitude of a star is a value that represents a star’s perceived brightness. This is distinct from luminosity which represents how bright a star actually is while magnitude represents how bright a star appears.

With magnitude, the lower the value, the higher the brightness. 1st magnitude stars are the brightest tier, 2nd magnitude stars are the second brightest, then third, and so on. This is a long-standing convention as old as ancient Greece when Hipparchus first categorized stars this way. Also, remember that this scale is logarithmic, not linear. Stars of a particular magnitude are defined as 100 times brighter than stars five magnitudes lower. This means that 1st-magnitude stars shine 100 times brighter than 6th-magnitude stars. 2nd-magnitude is 100 times brighter than 7th-magnitude, and so on.

🔅Stars with magnitudes brighter than +1.5, meaning a value of +1.5 or lower, are called 1st-magnitude. There are only about 20 stars in this category. The brightest star in the night sky is Sirius with an apparent magnitude of -1.46.

🔅Stars with magnitudes between +1.5 and +2.5 are 2nd-magnitude stars.

🔅The dimmest stars that the human eye can see are 6th-magnitude stars.

🔅The dimmest stars a 50mm pair of binoculars can see are 9th-magnitude stars.

🔅The dimmest stars a 6-inch amateur telescope can see are 13th magnitude stars.

🔅The Hubble Space Telescope has observed objects as faint as 31st-magnitude.

APPARENT MAGNITUDE (m)

Apparent magnitude is the brightness of a star as observed from Earth, which is how they appear to us when simply looking up at the sky. This depends on an object's luminosity (its intrinsic brightness) compared to its distance, as well as other factors that could reduce its perceived brightness, like being eclipsed by another object or medium, or increase its perceived brightness, like gravitational lensing.

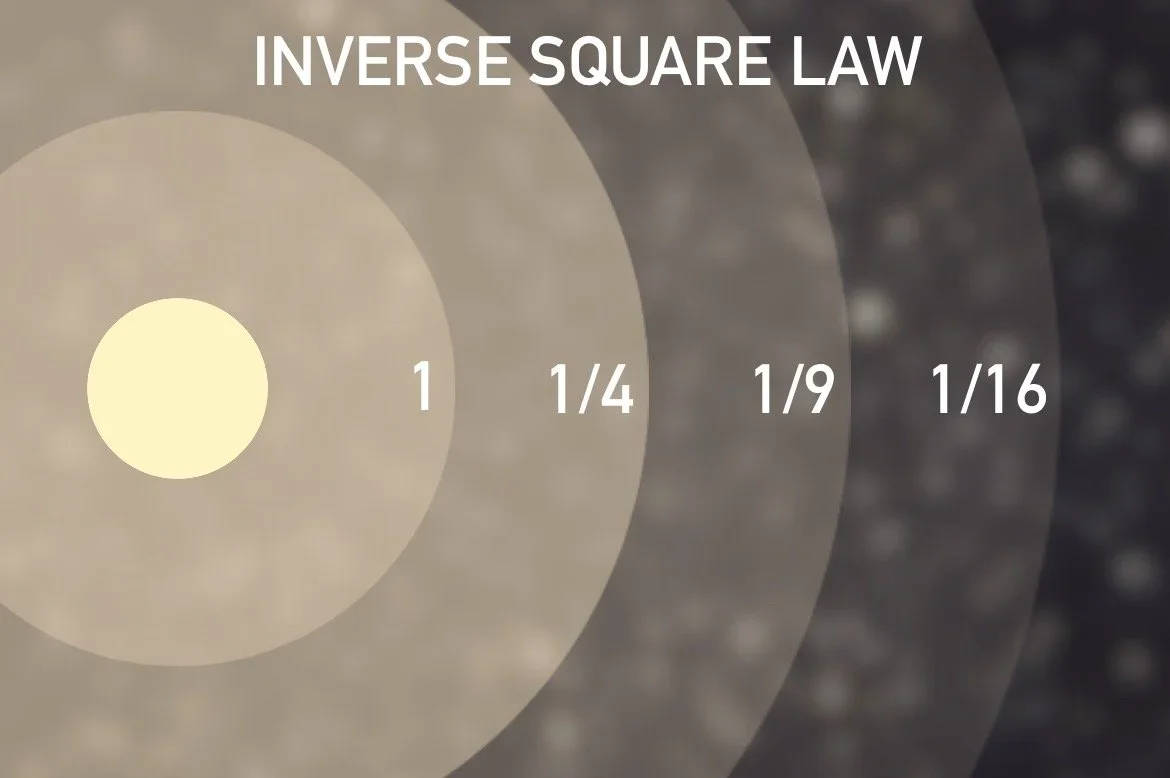

To determine a star’s luminosity, we compare apparent magnitude with its distance. Remember that brightness, just like gravity, decreases with the square of the distance. This means that if a star is twice as far away, it is four times dimmer. If it is ten times as far, it is a hundred times dimmer.

There are tons of stars that are tens to hundreds of thousands of times more luminous than Sirius, yet Sirius appears brighter than every single one of them because it is much, much closer at only 8.6 light years away.

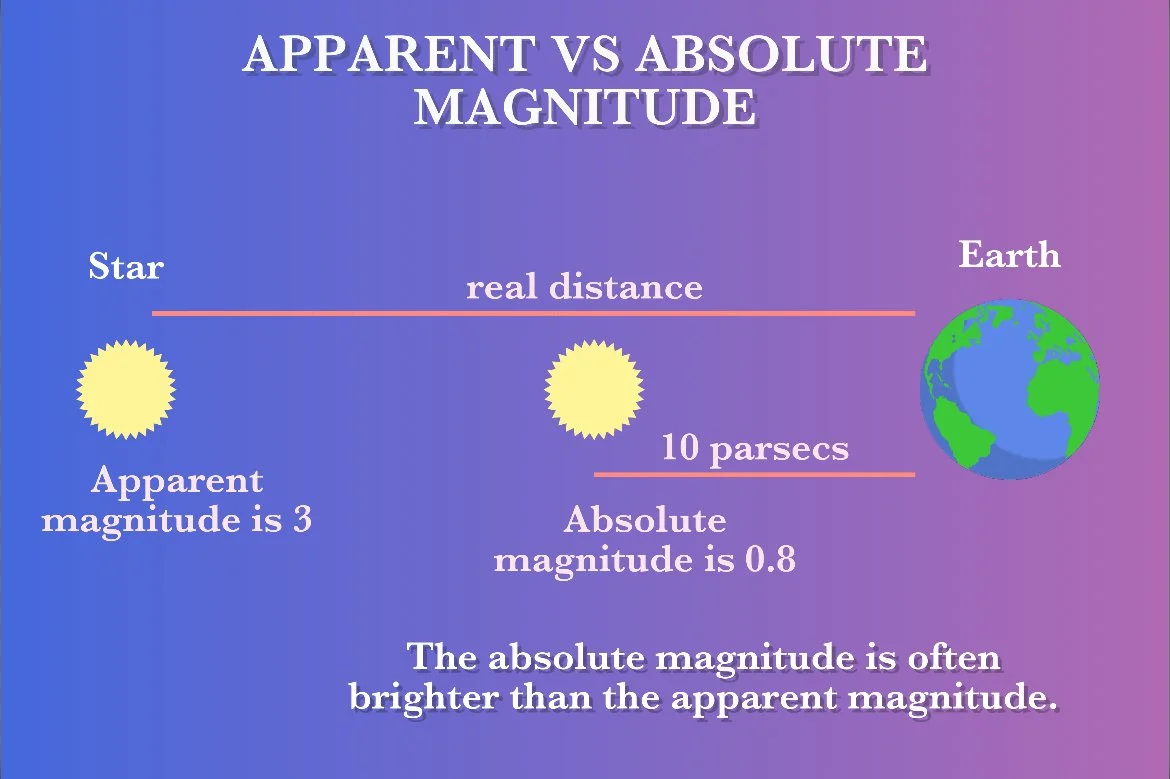

ABSOLUTE MAGNITUDE (M)

Absolute magnitude is the brightness of a star if it were placed at a distance of 10 parsecs from Earth, or 32.6 light years. Determining this value allows you to compare the brightness of two stars from the same distance.

Why 10 parsecs? It is mostly arbitrary but not without reason. The idea was for astronomers to pick a number that was not too close but not too far. Too close and the numbers would get unnecessarily high. Too far and the stars would be too faint to measure accurately. 10 parsecs were decided to be kind of the “sweet spot.” At this distance, the vast majority of stars have a much higher absolute magnitude than their apparent magnitude. For a small number of stars, it’s the other way around. For example, the Sun has a dramatically lower absolute magnitude. Its apparent magnitude is -26.7, but from 10 parsecs away it becomes a meager +4.83.

MEASURING DISTANCE

Stars are far away. I mean, really far away. However far away you are imagining, they are further than that. But how do we actually know that? It’s not like we took a tape measurer out to the furthest reaches of the cosmos. Over the years, humans have developed a number of intuitive ways to determine the distance of some really distant stars. Before we dive into some of the more prominent methods, let’s consider our units of measurement:

When talking about measuring the distance to stars, it makes sense to start with the astronomical unit (AU) which represents the average distance between Earth and the closest star, the Sun. This is about 150 million kilometers or 93 million miles. However, the Sun is really the only star where this unit of measurement is practical. This is because all other stars are so much further away. For example, the furthest planet from the Sun is Neptune which is about 30 AU away. Let’s compare that with the closest star to the Sun, which is Proxima Centauri. Sticking with the same unit of measurement, it is 268,200 AU away. Let’s switch to a more appropriate unit.

Next, we have the light year (ly). This is the distance that light travels in a single Earth year. Light moves incredibly fast (though not instantaneously). Get ready for this: a light year is about 9.5 trillion kilometers or 6 trillion miles. This takes Proxima Centauri from 268,200 AU down to 4.24 light years, a much more manageable number.

Then, we have the parsec (pc). Yes, contrary to what Han Solo will tell you, a parsec is a unit of distance, not a unit of time. A parsec is defined as the distance at which a star would have a parallax angle of 1 arcsecond (1/3600 of a degree). We’ll get into what parallax is shortly. For now, just know that one parsec is equal to about 3.26 light years. So, if an astronomer says that a star is 10 parsecs away, that means it is 32.6 light years away. This unit of measurement is more of use to professional astronomers who spend a lot of time dealing with parallax.

Okay, let’s get into how we actually figure out the distance of stars. Over the years, astronomers have developed a variety of methods, each one suited to particular types of stars and ranges of distance. While each technique has its strengths and limitations, we will focus on two of the most foundational approaches.

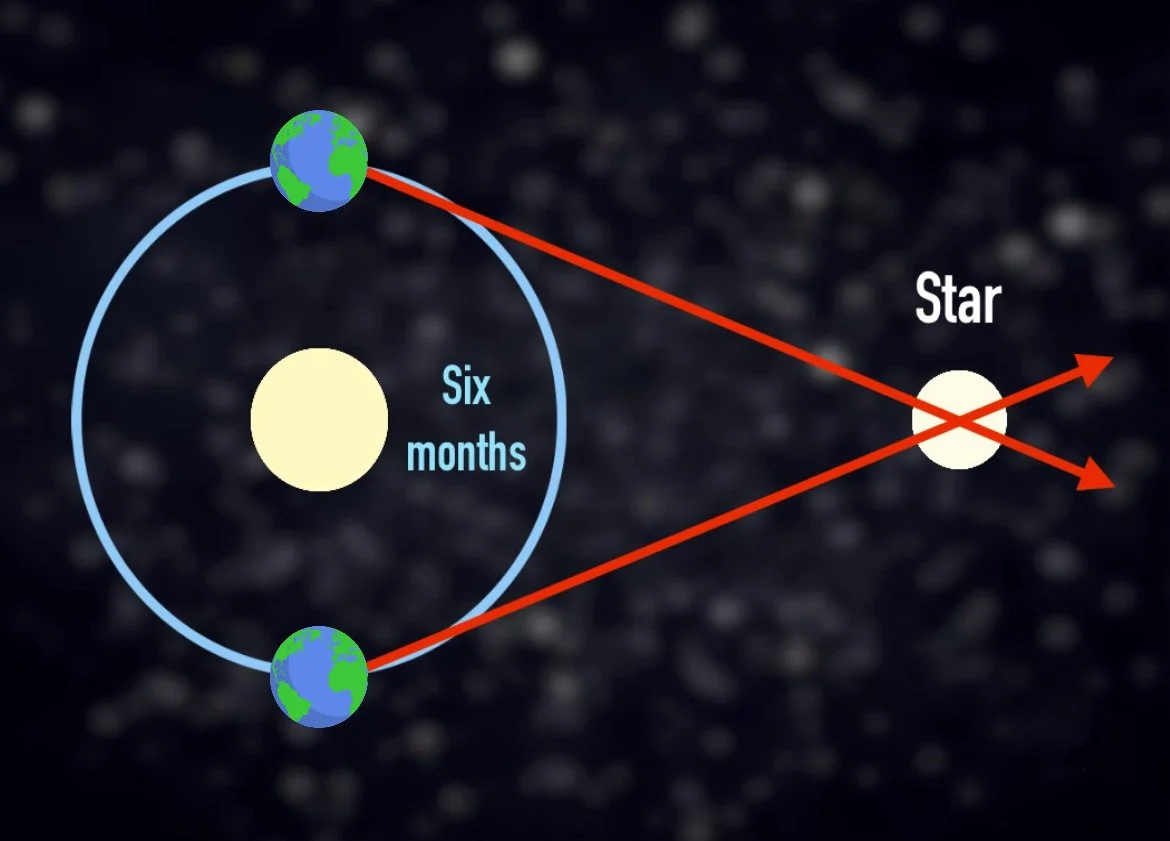

PARALLAX

If you hold up one of your fingers in front of your face. Then, alternate between closing one eye and then the other. You’ll notice your finger appears to move back and forth. This is because each eye is seeing the finger from a different angle. The closer you hold your finger, the more pronounced this movement is because the angle becomes greater. If you move your finger away, it gets less pronounced. Were you able to move it far enough away, you’d stop being able to perceive the difference. If you could only increase the distance between your eyes, you’d be able to see this same kind of movement with distant stars. Turns out, you can if you’ve got the time.

The concept of parallax has existed since ancient times, but it wasn’t until the 19th century that we started measuring the distance of stars using parallax successfully. Here’s how it works: Scientists observe a star, taking note of its position relative to the background stars. Then, they wait six months for the Earth to orbit around to the opposite side of the Sun, putting approximately 2 AU of distance between them and that first observation. When they observe the star again, it will have moved some amount relative to the background stars. This is known as the parallax angle. The greater the angle, the closer the star. An angle of 1 arcsecond (1/3600 of a degree) means a distance of 3.26 light years, which is the basis for the parsec unit of measurement.

The effectiveness of parallax wanes with distance as the parallax angles get smaller. Ground-based telescopes can accurately measure the parallax of stars within a few hundred light years. Space telescopes, which are free from the blur of Earth’s atmosphere, can see much further. The recently retired Gaia space telescope was so precise that it could measure parallax within tens of thousands of light years, which essentially covers a large portion of the Milky Way galaxy.

STANDARD CANDLES

For much of history, astronomers could barely measure the distance of nearby stars with parallax. One of the biggest limitations across astronomy up to that point had been that we didn’t know the intrinsic brightness of any object beyond parallax range.

If you know both a star’s apparent magnitude and its absolute magnitude, then determining its distance becomes a simple math problem. Light weakens with distance via the inverse square law, meaning it decreases with a square of the distance. If you double the distance, the light becomes 2 x 2 = 4 times weaker (or 1/4 its initial brightness). If you make the distance x10 further, the light becomes 10 x 10 = 100 times weaker (or 1/100 its initial brightness). Because this dimming is predictable, you can determine how much distance is required to go from the apparent magnitude to the absolute magnitude.

In the early twentieth century, we developed brand new methods that would act as a supplement to parallax: standard candles.

American astronomer Henrietta Swan Leavitt had been studying Cepheid variables, stars that pulsate at regular intervals, and discovered a very peculiar relationship between the duration of their pulsations and the intensity of their brightness. Cepheids that pulsated more slowly were brighter. This period-luminosity relationship meant that if one could know the period of a Cepheid’s pulsation, you could know its intrinsic brightness. Then, you needed only compare that with its apparent magnitude and you could actually discern its distance via the inverse square law, even if it was beyond parallax range. The discovery of this interesting quirk singlehandedly reconfigured our conception of the universe which was profoundly larger than we’d ever imagined.

Another reliable standard candle we’ve found is Type Ia supernovae. These occur in binary systems where a small white dwarf is siphoning material off of a larger companion. Remember, white dwarfs can only remain stable if their mass remains below the Chandrasekhar limit (1.44 M☉). Were they to gain enough mass to reach this limit, electron degeneracy pressure would fail and they would collapse, triggering a supernova. This is what happens in these binary systems. Because the mass that triggers these supernovae is consistently the same, the brightness of the supernovae is also consistently the same. Therefore, if we know the apparent magnitude of the supernovae, we can also know their intrinsic brightness. Then, it’s just a matter of calculating the inverse square law.

The range of standard candles far outpaces that of parallax. Cepheids can be measured up to 40 million light years where Type Ia supernovae can be measured into the billions of light years. There are many more niche methods that cater to specific situations, but these two are the most common.

MEASURING AGE

One of the trickiest aspects of astronomy is determining how old stars are. Their lives span millions to billions of years so we don’t have the ability to personally observe the full breadth of a single star’s evolution. Therefore, we must infer their age from observations of physical characteristics that stars have at the time astronomers observe them.

By taking a star’s brightness and temperature and plotting it on the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram, we can see what stage of evolution it’s in. Stars spend most of their lives on the main sequence. This takes a much, much longer time for dimmer, cooler stars than it does for brighter, hotter stars. This is because more mass exerts more gravity, more gravity creates more pressure in the core, more pressure generates more heat, more heat triggers faster fusion. The more mass, the faster a star burns through its fuel. Therefore, determining the mass of a star is a good first step to determining its age.

The most reliable method comes from when stars are born, not in solitude, but as part of a star cluster. In these instances, stars are born from the same nebula around the same time. With every star being roughly the same age, all astronomers need to do is plot each star in a cluster on the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram. At some point, the pattern will show stars start to peel off and move up into the giant branches above. This is known as the turnoff point. The stars in this cluster with the highest mass (aka the brightest and hottest) have the shortest lifespans, so they will be the first stars to evolve off the main sequence. By identifying where in the main sequence this turnoff point happens, scientists can reveal the general age of the star cluster as a whole.

Determining the age of single, solitary stars is a much more uncertain prospect. Without the turnoff point found in clusters or measuring the orbital characteristics of a binary pair, we don’t have a way to accurately determine its mass. In fact, there’s really only one star we know the age of with great confidence: the Sun. This is because we were able to physically collect the oldest rocks in the solar system and apply radiometric dating techniques to determine the solar system’s age, which is about 4.6 billion years old. We obviously can’t do that with any other star, but we aren’t completely disarmed.

Of course, plotting a star on the HR diagram is a good launching off point, but only gives us a rough estimate of its expected lifespan. Stars change subtly over time and there are some things we can look at to help determine where they’re at in their expected lifespan.

Luminosity: As main sequence stars age, helium builds up in their cores. The denser core then contracts and produces more energy from fusion. Thus, the luminosity gradually increases. This is far more evident in high-mass stars which evolve much faster than low-mass stars.

Rotation rate and magnetic activity: The convective layers of conductive plasma stars drive magnetic dynamos which cause the stellar wind to co-rotate with the star. As stellar wind escapes, the star loses angular momentum, and its rotation slows over time. This is called magnetic braking. As the rotation slows, the magnetic dynamo weakens. This creates an interesting feedback loop. Granted this shift flattens with time so it’s not as useful for older stars.

Astroseismology: Otherwise known as starquakes, we can observe subtle oscillations in the light curve of stars caused by reverberations in their interiors. This can reveal the density of the star and thus how much helium is building up.

Lastly, stars can have unique features that clue us into where they are in their evolution. For example, very young stars will still have a protoplanetary disk around them. Conversely, massive stars nearing the end of their life will start to dump large quantities of gas and dust into interstellar space before going supernova.

STELLAR POPULATIONS

Astronomers also work to determine a star’s generation. As stars age, they fuse lighter elements into heavier ones, especially high-mass stars which fuse a ton of elements very quickly. When these stars die, via shedding their outer layers through stellar winds or through a supernova, they return enriched material to interstellar space. This gas, now containing heavier elements, can eventually collapse to form new stars. Stars formed from this recycled material have a higher proportion of heavy elements, or “metals” in astronomical terminology, than earlier generations. Each successive generation of stars thus continues to enrich the universe with metals.

By analyzing a star’s metallicity, astronomers can estimate when in the universe’s history it formed, using spectroscopy to identify the abundance of elements heavier than hydrogen and helium. Stars are categorized into three population types:

Population I consists of relatively young, metal-rich stars. These stars formed from nebulae that had already been enriched by many generations of previous stars.

Population II consists of older, metal-poor stars. They formed from gas that had seen only a few prior cycles of star formation.

Population III consists of the first stars ever formed. Born from pristine hydrogen and helium, they contained no heavier elements. These hypothetical stars played a crucial role in reionizing the early universe and seeding it with the first metals, though none have been directly observed.

Stars are celestial engines that are powered by the cyclical relationship between gravity, mass and energy. They converge to form some of the greatest singular structures in the universe and giving rise to countless worlds around them. We wouldn’t be here without them.

If you or anyone you know are looking for guidance on learning about these celestial engines, members of the Harford County Astronomical Society are here for you to provide our enthusiastic knowledge and experience.

Come find us at future events or fill out an outreach request and ask for assistance and we will do what we can!