THE SUN

The shining jewel at the center of the solar system.

Mass: 330,000 x Earth

Diameter: 1.4 million km

Age: 4.6 billion years

Surface temperature: 5,800 K

Core temperature: 15,000,000 K

Few objects in human history have been revered across nearly every ancient culture as profoundly as the Sun. From the towering pyramids of Egypt aligned with solstices to the intricate solar calendars of the Mayans, the Sun has shaped architecture, agriculture, and rituals across continents. Central to the rhythms of everyday life, the Sun told people when to wake up and go to sleep, when it was time to plant and harvest their crops, what direction to sail their ships, and what holidays were upon them. Its importance even transcended the practical, guiding higher pursuits. The Sun has been the subject of countless pieces of poetry, art, theater and music. Many civilizations even worshipped the Sun as a god that embodied creation, authority and cosmic order.

With a single object commanding such unparalleled importance to our existence, we ask an equally important question: What actually is the Sun?

The Sun is a star. While it is large and luminous in ways others don’t seem to be, the Sun is fundamentally the same thing as those tiny points of twinkling light we see spread across the night sky. What makes ours special is how close it is.

The Sun lies at the center of our solar system which everything else revolves around. It formed about 4.6 billion years ago from the gravitational collapse of a nebula. It is primarily composed of a massive amount of hydrogen and helium. The Sun’s immense mass corresponds with its equally immense gravity, which condenses itself inward and squeezes material in the core. This extreme pressure heats up the core to temperatures so extreme that it causes the hydrogen atoms in the core to fuse together into helium. This process is called thermonuclear fusion. Every second, the Sun fuses about 600 million tons of hydrogen into helium and converts another 4 million tons into energy, which it radiates out in the form of light and heat. The radiating energy’s outward pressure is matched against the Sun’s inward gravity. This balance is known as hydrostatic equilibrium and is what maintains its stable form. It will be maintained until one force overcomes the other. Hint: one of these forces is finite, and the other isn’t.

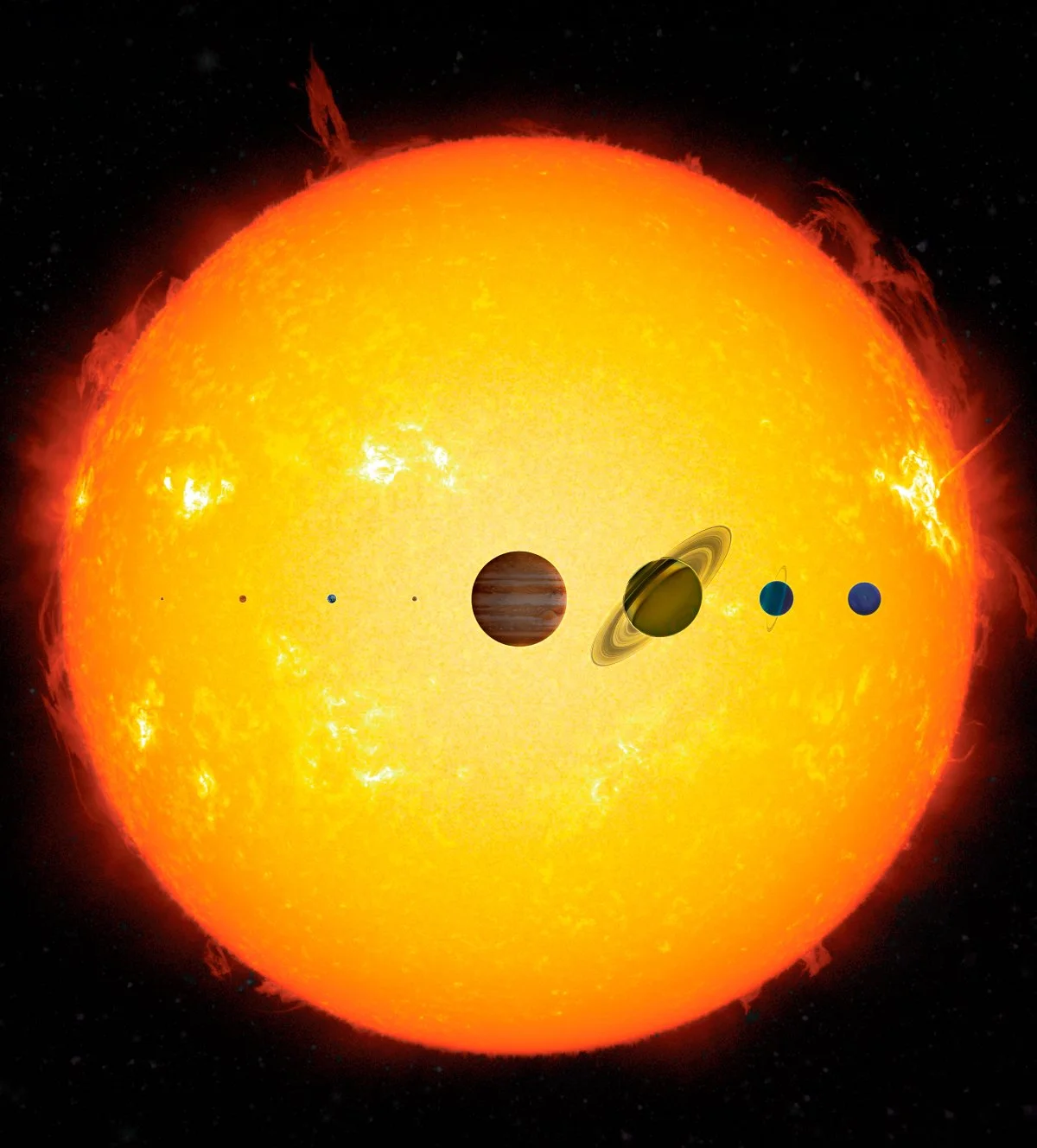

As a G-type star, the Sun is bigger than most stars but nowhere near as big as stars can get. However, it is unmatched in its own domain. The Sun’s diameter is 10 times wider than the largest planet, Jupiter, and 109 times wider than our home planet, Earth. This means that you could fit about 1,000 Jupiters or 1.3 million Earths within the Sun’s entire volume. If a commercial airplane were to fly around the Sun at its surface, traveling at 550 mph, it would take 206 days (6.8 months) to complete one revolution.

Even more impressive, the Sun makes up about 99.85% of all the mass in the solar system. Jupiter comes in at a distant second with 0.1%, or 70% of the remaining mass.

The Sun is astoundingly bright, able to wash out almost every other celestial object in daylight. Its apparent magnitude is recorded as -26.8. For comparison, the full moon is just -12.74 and the next brightest star, Sirius, is only -1.46. Remember, with the magnitude scale, a lower number means a brighter object, and the scale is logarithmic, which reverses the way exponential differences in brightness are counted (each step represents a large jump in brightness rather than a small, linear change). The Sun is 400,000 times brighter than the full moon and 12 billion times brighter than Sirius (though Sirius is much more luminous than the Sun at the same distance).

⚠️Warning: Never look directly at the Sun without approved solar glasses or a solar telescope filter. Otherwise, you could risk permanent eye damage and/or blindness.

Remember, the Sun is only so much brighter than other stars because it’s so much closer. Placed at the distance of even some of the closer stars in our night sky, and we see the Sun in a very different way. The Sun’s absolute magnitude, how bright it appears from a uniform distance of 32.6 light years away, becomes just +4.83. At this distance the Sun would appear as a point of light, barely visible to the naked eye.

It is a common misconception that the Sun is yellow. Its true color is actually white. The reason we often see it as yellow, and sometimes red, has to do with how light scatters when it enters the Earth's atmosphere. Blue wavelengths get scattered more, which turns the Sun’s white light to yellow. As the Sun gets lower and lower in the sky, its light passes through the atmosphere at a lower angle, meaning the blue light is scattered more and more, eventually turning orange or red. However, if you were to get enough altitude above the atmosphere, you'll see a white Sun.

LAYERS OF THE SUN

The core is the central region of the Sun where thermonuclear fusion occurs and produces all of the Sun’s energy. It is by far the hottest and densest region of the star.

The radiation zone is the middle region of the Sun’s interior where energy travels through from the core in the form of electromagnetic radiation. Due to the density of this region, photons bounce from particle to particle and can take millions of years to escape.

The convection zone is the outermost layer of the Sun’s interior where hot material from near the star’s core rises, then cools at the surface and plunges back downward. These convective motions are visible at the surface in the form of granules.

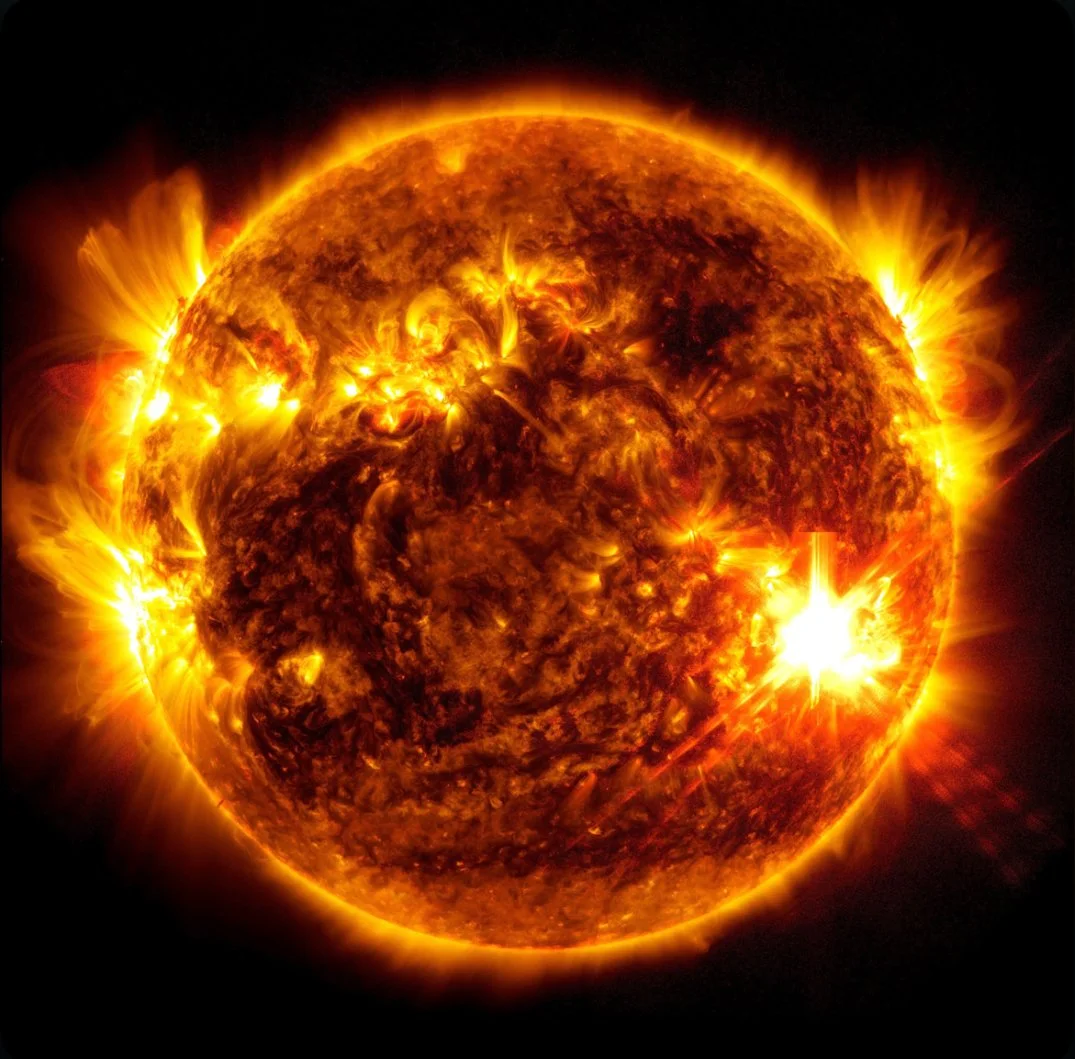

The photosphere is the innermost layer of the Sun’s atmosphere. It is essentially the visible surface of the Sun from which light is finally able to radiate freely out into space. It is the thinnest, coolest layer and has a granulated appearance due to the convection beneath. It can also feature darker, cooler regions called sunspots.

The chromosphere is the transparent middle layer of the Sun’s atmosphere. Despite being further from the star’s core, it is hotter than the photosphere. It is difficult to see unless you have special equipment or are viewing it during a solar eclipse. One of its most recognizable features are the grass-like spicules.

The corona is the outermost shell of the Sun’s atmosphere. It is an extremely hot zone caused by the transport of energy from the layers below by means of magnetic fields. Like the chromosphere, it is mostly only visible during a solar eclipse. There is a special kind of telescope called a coronagraph that makes it possible to see this region and search for exoplanets.

SURFACE FEATURES

Granules are small cell-like structures that cover the entire photosphere, or “surface,” of the Sun. They bubble up in the bright middle via the convection of hot plasma within the Sun's interior, then after 8-20 minutes of cooling, they sink back down at the darker edges, only to be replaced by another. They tend to be 1,000-2,000 km in diameter, meaning as few as six granules could span the diameter of the Earth.

Spicules are jet-like structures like flickering flames projecting outward from the Sun’s surface. These dynamic, wispy eruptions appear and disappear within minutes, like granules, typically reaching 5,000-9,000 km high. They are thought to be formed by the sudden release of magnetic energy, which propels plasma upwards from the photosphere into the Sun's chromosphere. It could explain why the latter is so much hotter than the former.

Sunspots are dark blemishes that appear on the Sun’s photosphere. They originate where the Sun’s magnetic field is extremely concentrated and strong. This inhibits the convection of hot plasma from the Sun’s interior to the surface which causes the region to cool down significantly. As a result of the lower temperature, the region becomes darker. Sunspots are often easily visible when looking at the Sun through a solar filter, even unmagnified.

Prominences are large looping filaments of plasma anchored to the Sun’s surface and shaped by its magnetic field. They are associated with active regions where intense magnetic fields emerge and often reach hundreds of thousands of kilometers into the solar corona. The magnetic structure can become unstable and allow a prominence to erupt outward in dramatic fashion. These eruptions can generate mass coronal ejections (CMEs) that affect Earth.

Coronal mass ejections (CMEs) are huge clouds of plasma hurled into space, typically resulting from the sudden release of energy in twisted magnetic fields near active regions on the Sun. They carry massive amounts of matter and energy, often much more than a flare, but travel more slowly, taking days to reach Earth. When a CME interacts with Earth’s magnetic field, it can cause geomagnetic storms, disrupt satellites and power grids, and create spectacular aurorae visible even at lower latitudes.

Solar flares are intense eruptions of plasma and electromagnetic radiation, often originating around sunspots. They occur when energy built up in tangled and twisted magnetic fields is suddenly released. Unlike coronal mass ejections, flares do not usually eject large amounts of matter, but their radiation travels at the speed of light and can reach Earth within minutes. This energy can cause localized disruptions, such as radio blackouts, interfere with satellite communications, and pose risks to astronauts and high-altitude airline passengers.

MAGNETIC FIELD

Just like the planets, the Sun has a magnetic field and by this point you’ve probably noticed that a lot of the Sun’s activity seems to be heavily influenced by it. But what exactly is it?

A magnetic field is an invisible region in which magnetic forces act on moving charged particles, often visualized as lines forming closed loops that extend far into space. In planets, these magnetic fields are generated by the churning of electrically conductive liquid metal in their cores. This is called a dynamo. The Sun does not have significant amounts of metal in its core. Instead, the Sun’s magnetic field is generated by the motion of ionized plasma that flows throughout its convection zone.

The Sun’s differential rotation (slower at the poles, faster at the equator) stretches its magnetic field in a process called the omega effect, amplifying their strength. Convection of hot plasma, combined with rotation, twists these fields into looping helices in the alpha effect, which can realign them pole-to-pole. Together, the alpha and omega effects sustain the Sun’s dynamo and magnetic cycles, with much of this activity concentrated in the tachocline, a narrow region at the base of the convection zone.

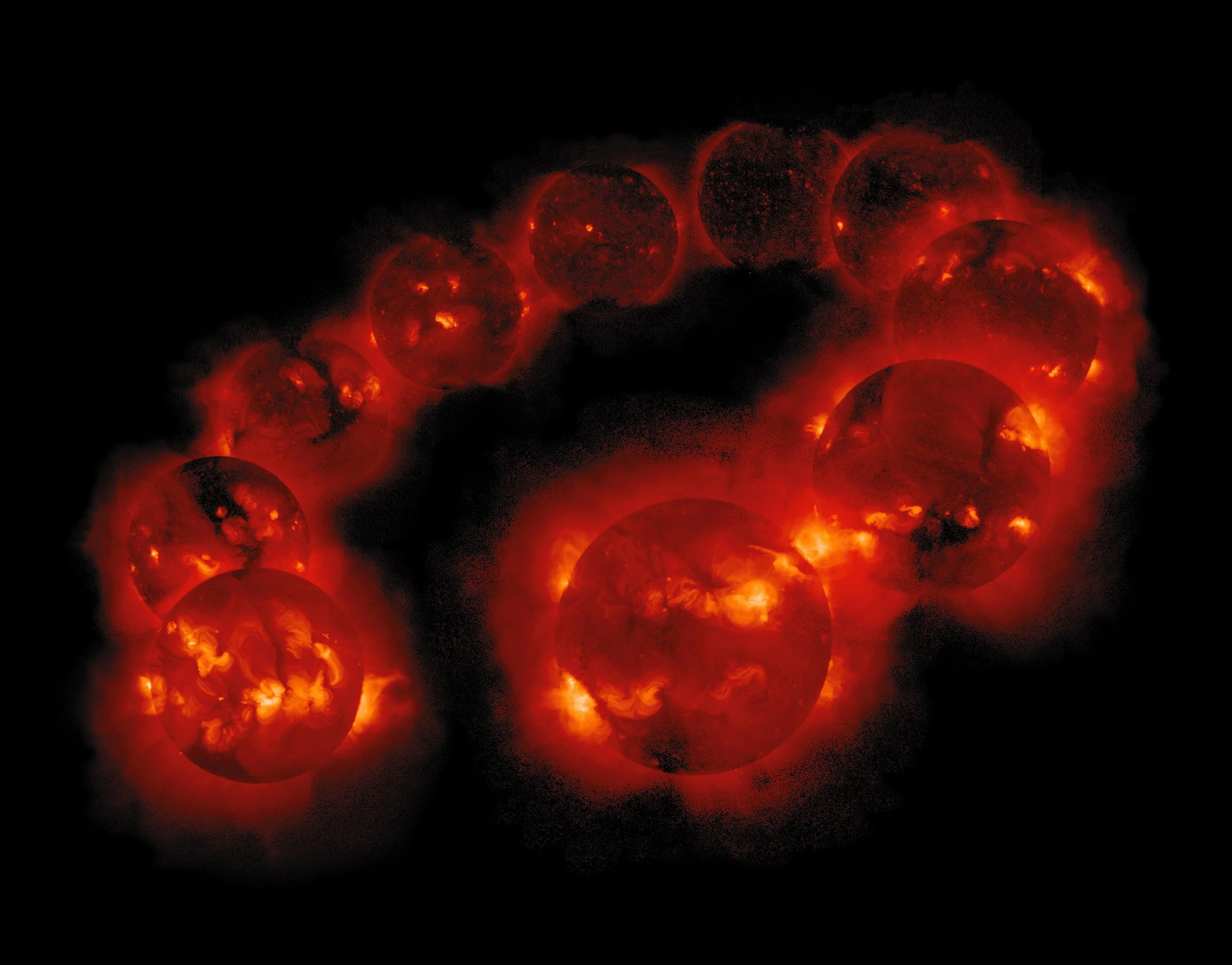

SOLAR CYCLE

The Sun goes through an approximately 11-year solar cycle, first identified in 1843 by Samuel Schwabe, in which its magnetic field swings between calm and stormy states. At solar minimum, activity is low, with few small sunspots near the equator and only occasional weak solar flares or coronal mass ejections. As the Sun’s magnetic field becomes stretched and twisted, it builds up a reserve of energy and surface activity increases. When the Sun reaches solar maximum, sunspots, solar flares, coronal mass ejections become intense and frequent. These bursts of plasma can disrupt satellites, power grids, and astronaut safety, but they also generate spectacular aurorae that, during strong storms, can even be seen at unusually low latitudes like Maryland.

You can dive deeper into the Sun’s magnetic field and solar cycle here.

SOLAR WIND & THE HELIOSPHERE

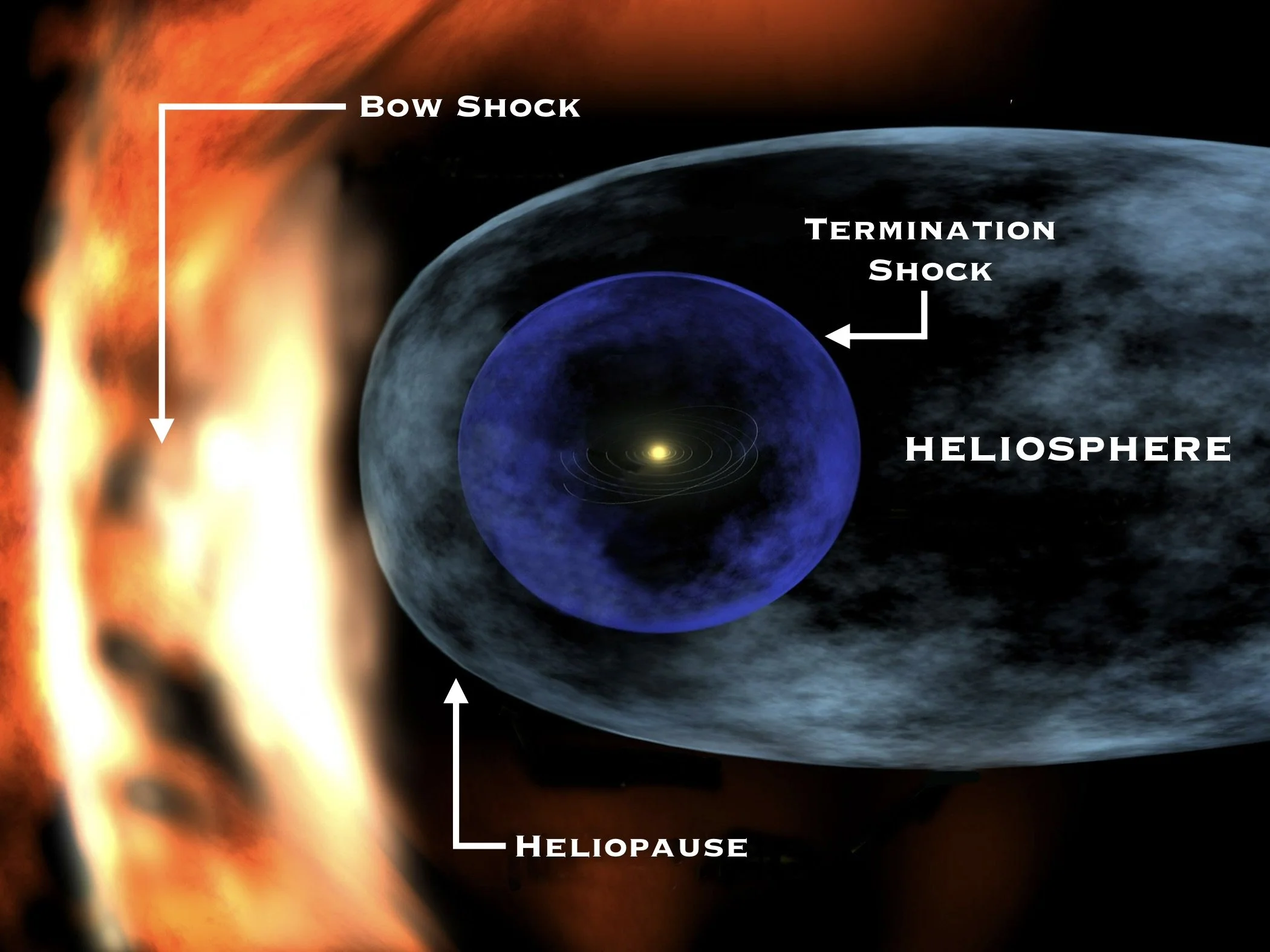

The Sun is constantly releasing material into space. From its outer atmosphere, the corona, flows a continuous stream of charged particles called the solar wind. This plasma, composed mainly of electrons and protons, escapes the Sun’s gravity due to extreme temperatures and moves outward at hundreds of kilometers per second. Faster wind emerges from coronal holes where magnetic field lines open into space, while slower wind comes from more magnetically closed regions. Though extremely thin, the solar wind carries the Sun’s magnetic field throughout the solar system and can intensify during periods of high solar activity.

This outward flow inflates a vast bubble known as the heliosphere, which surrounds the solar system and extends beyond the orbit of Pluto. Within this region, the Sun’s magnetic influence dominates over interstellar space. As the wind expands, it slows at the termination shock and meets interstellar resistance at the heliopause, the outer boundary of the Sun’s reach. The heliosphere helps shield the solar system from high-energy galactic cosmic rays and changes in size over the solar cycle. As the Sun orbits the galactic center, the heliosphere plows through the interstellar medium, forming a bow shock, much like a boat plows through water.