MERCURY

The closest planet to the Sun.

Distance from the Sun: 58 million km (0.4 AU)

Diameter: 4,880 km

Rotation period: 59 days

Orbital period: 88 days

The most elusive and fleeting planet in our solar system is undoubtedly Mercury. It reveals itself only in brief windows at dawn or dusk, seemingly tethered to the Sun by an invisible leash. After gleaming against the twilight, it either dissolves into the growing morning light or slips beneath the dimming evening horizon. For most of human history, this made Mercury difficult to track and easy to lose.

As the closest planet to the Sun, Mercury requires the fastest orbit to keep from falling in. This is why it’s named after the swift-footed messenger god in Roman mythology. From Mercury’s surface, the Sun dominates the sky in a way unmatched by anywhere else. It appears as large as three times wider than it does from Earth and shines with nearly eleven times the intensity.

Furthermore, Mercury has the highest orbital eccentricity and inclination of any planet. This is to say its orbit is the most stretched and has the greatest tilt with respect to Earth’s orbit.

Just like Venus, Mercury is closer to the Sun than Earth. This means that it occasionally passes between the two. Most times, the 7° incline of Mercury’s orbit puts it too far above or below the Sun to be visible. It is rare, but every once in a while, the three bodies will line up just right and Mercury will appear to cross right in front of the Sun from our vantage point. This is called a transit and for Mercury it happens about 13-14 times per century. With the proper protection, astronomers can witness this happening through even small telescopes. The last time Mercury transited the Sun was in 2019 and the next one will be in 2032.

⚠️Warning: Never look directly at the Sun without approved solar glasses or solar telescope filter. Otherwise, you could risk permanent eye damage and/or blindness.

Another interesting quirk of Mercury’s orbit involves tidal forces (the stretching of an object via gravity). Just as the Earth exacts a tidal force on the Moon and vice versa, so too does the Sun exact a tidal force on the planets, with Mercury feeling this force the strongest. For the Moon, this causes it to become tidally locked where the same side is always facing the Earth. However, Mercury’s orbit is highly eccentric, meaning it varies greatly in distance throughout a single revolution around the Sun and thus alternates between a faster and slower orbit. The end result is not quite tidal locking but a 2:3 spin-orbit resonance, rotating on its axis exactly three times for every two revolutions around the Sun. This means that a solar day on Mercury (sunrise to sunrise) lasts 176 Earth days (twice as long as its year) with 88 days spent in constant sunlight and 88 days spent in constant darkness.

At about only a third the diameter of Earth and only one and a half of Earth’s Moon across, Mercury is the smallest planet in the solar system. However, there’s a lot packed into this small package. Mercury is the second densest object in the solar system, just slightly behind Earth. This is likely attributed to its disproportionately large iron core, compared to the other terrestrial planets, making up over half the planet’s volume. The core is surrounded by a layer of silicate rock that acts as the planet’s surface. There are a few hypotheses as to why the core is so much bigger than its mantle. Many scientists believe the rocky shell was chipped away by numerous collisions over time, but more recent ideas are that the Sun’s powerful magnetic field pulled iron molecules inward early in the solar system’s formation.

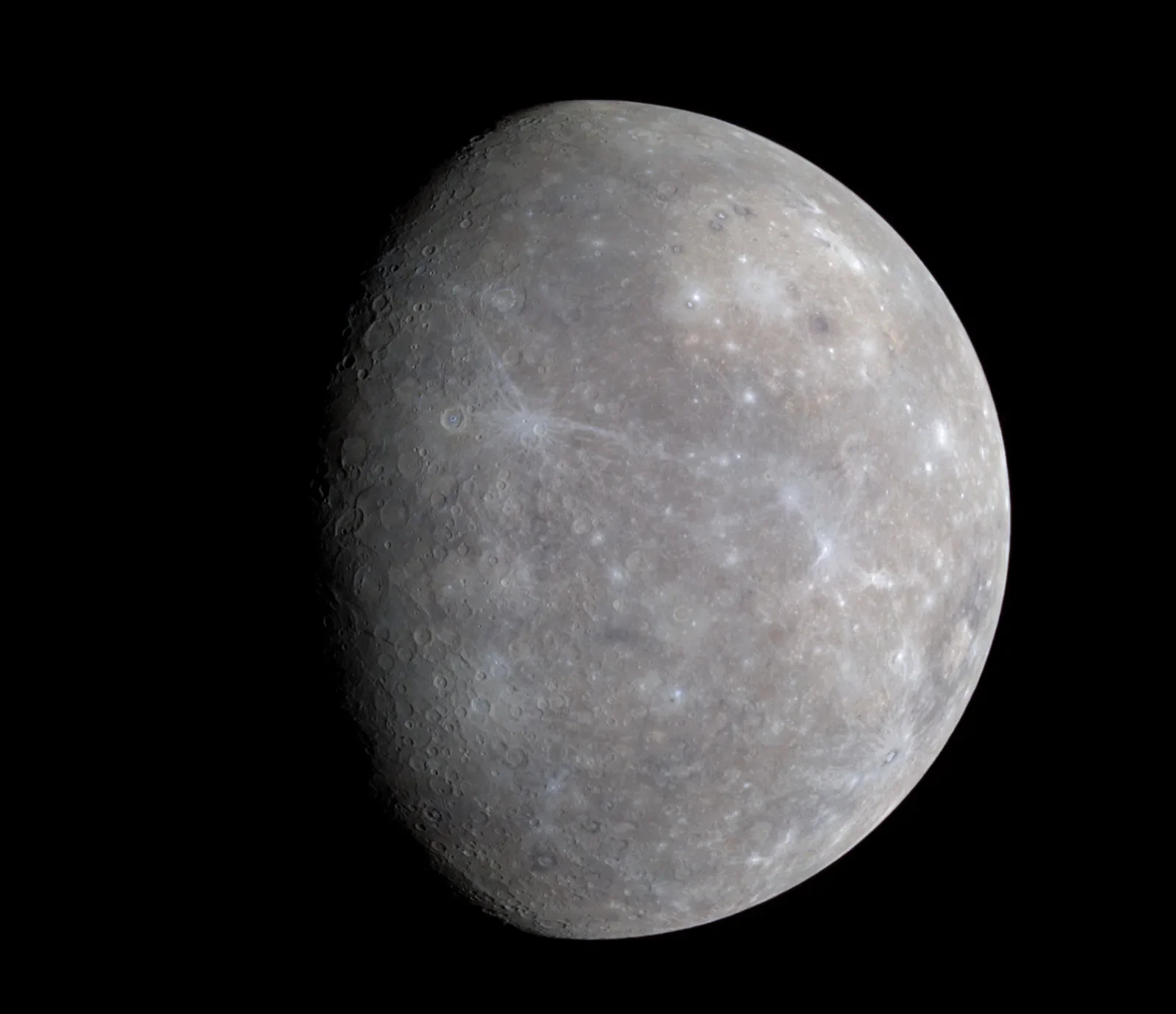

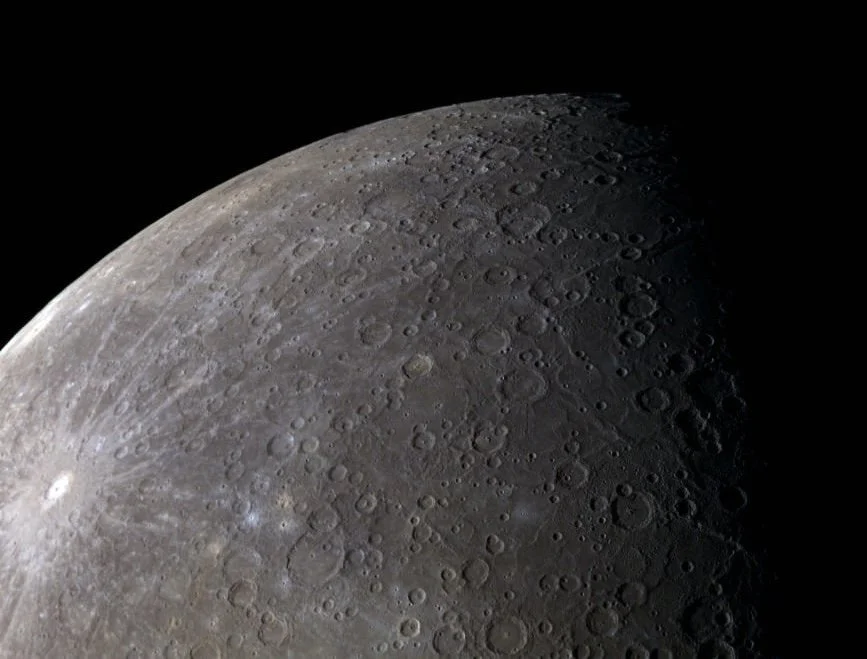

Looking at the Mercurial surface, you’ll see a barren expanse of rocky craters and not much else. For the most part, that’s all there is. In this way, Mercury is the planet that most resembles our Moon. Much of the surface is covered in solidified lava plains (similar to the Moon’s maria) from past volcanism. However, the planet hasn’t been geologically active for billions of years. Additionally, Mercury has little to no atmosphere to catch incoming meteors and burn them up before they can impact the surface. Without an atmosphere nor continuous resurfacing by lava, craters are left to accumulate over time. The craters range in size from small cavities to massive impact basins. Many of them are named after deceased writers, artists and musicians such as Shakespeare, Van Gogh and Beethoven.

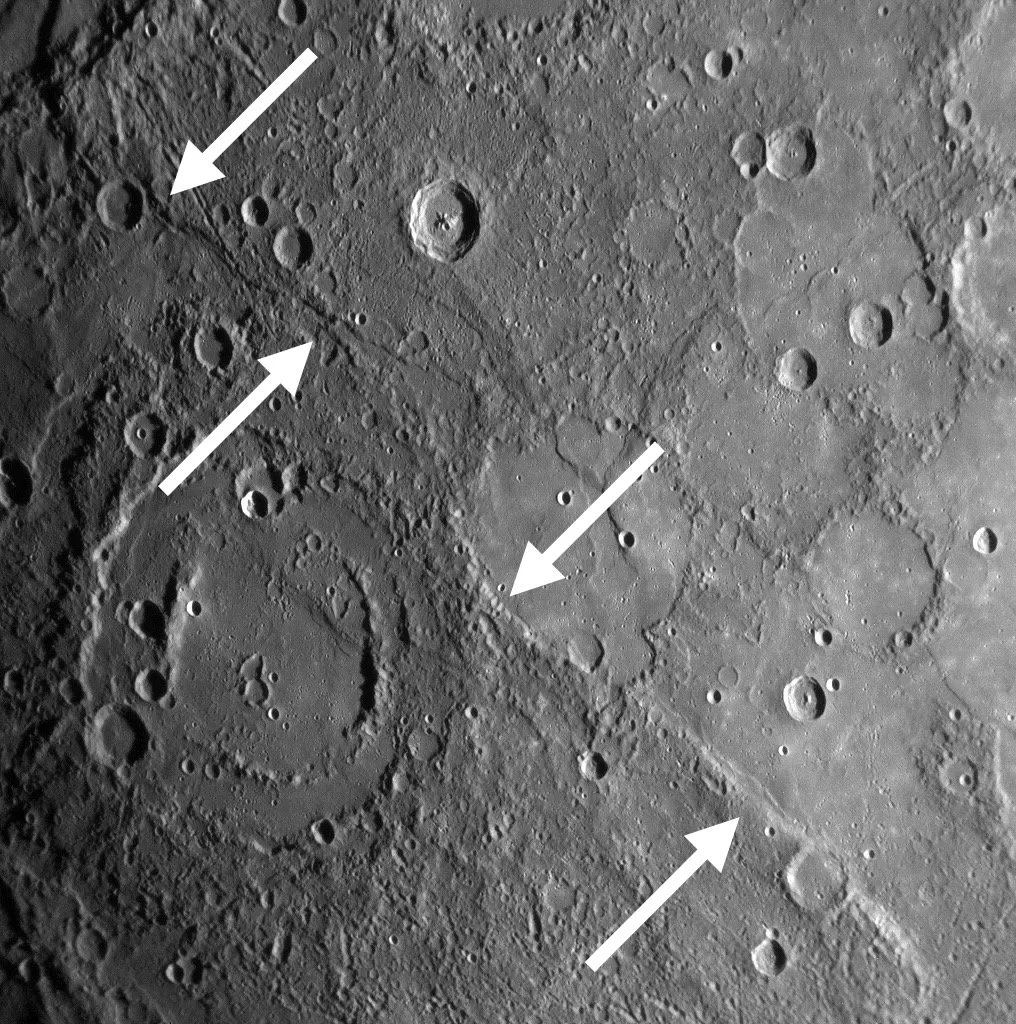

Some craters are surrounded by bright, radial streaks. These are crater rays, lanes of pulverized rock that were ejected by the meteor impact and spread outward across the surface. Without a swirling atmosphere to sweep them every which way, they are free to fall in neat, straight lines. These striking surface features are best exemplified by the northern Hokusai crater, which has a ray system extending across much of the planet. Over millions of years, exposure to the Sun’s intense solar winds and the gradual blanketing of dark space dust will fade ray craters.

Caloris Basin is the largest impact basin on Mercury’s surface, located near its equator. The word “Calor,” which is Latin for “heat,” is used to reference how the Sun passes almost directly overhead every other time Mercury reaches perihelion (its closest point to the Sun). In other words, these plains experience some of the most concentrated sunlight of any planet surface. Originating from a giant meteor collision during the early solar system (some 3.9 billion years ago), the impact basin spans about 1,550 km (about a third of Mercury’s diameter) and ringed by 2 km-high mountains. Within the crater walls, the floor is covered in relatively smooth lava plains which conceal now-dormant explosive vents below.

Spreading from the center of the impact basin are a series of spider-like radial fractures, known together as Pantheon Fossae. They formed not from the impact itself but from crustal stresses within the crater floor after it was filled with lava. Just off center of this formation is the unrelated impact crater, Apollodorus.

The planet doesn’t seem to be divided into moving tectonic plates like we see on Earth, but there are signs that the surface was shaped by ancient contractions when the interior was still cooling down. As the planet gradually shrank, the crust got immensely compressed and began to deform. This resulted in thrust faults in which one block of the crust is pushed up and over an adjacent block. Across the surface of Mercury, we see these thrust faults expressed in the form of lobate scarps.

These expansive features consist of steep cliffs on one side and a gentle down slope on the other side. From the side, they resemble swelling tsunami waves that were suddenly turned to rock. Just like craters, these cliffs range widely in size. Some reach just tens to a few hundred meters high while others can reach a few kilometers high and hundreds of kilometers wide. They are often bow or crescent shaped.

While many of these features date back to Mercury’s very early years, space probes like MESSENGER orbiter have discovered small, fresh-looking scarps as well. This suggests that the contraction of Mercury may have lasted much longer than previously thought and the planet might still be geological active today.

Mercury has the most extreme range of temperatures of any planet. Being so close to the Sun, Mercury is hit with 7 times the solar energy that Earth does. This puts its surface at a scorching temperature of 430°C (800°F) on the day side, hot enough to melt lead and zinc (though not quite hot enough to melt aluminum). This makes for one of the most blistering surfaces of any planet in the solar system. However, the night side of Mercury is a very different story. While Mercury does have a very faint exosphere, a thin collection of atoms blasted off the surface by striking meteoroids and solar wind, it’s nowhere near enough to maintain the blistering heat of the day side. Mercury gets extremely cold at night, dropping as low as -180°C (-290°F). As you can imagine, the repetition of such a dramatic swing in temperature causes a fair bit of stress on the surface, constantly expanding and contracting, and ultimately fracture.

Water molecules are known to accumulate on Mercury’s surface, mostly from comet impacts, but possibly also from outgassing from the planet’s interior. Mercury’s dark side is certainly cold enough to host frozen water, but regardless of how cold it gets at night, Mercury’s rotation will always bring that side around to the day where the water will be vaporized by the Sun’s blistering rays.

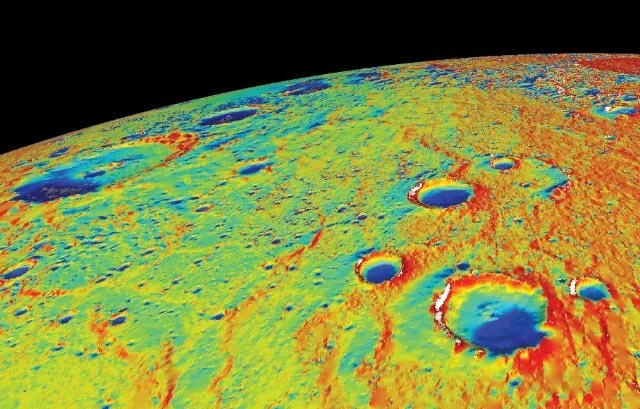

Due to Mercury having almost no axial tilt, there are places within craters around its polar regions that are permanently steeped in shadow. These regions are known as cold traps where water ice is free to pool on the crater floors. These reservoirs were directly observed by the MESSENGER orbiter in 2012 using a reflecting laser to detect the brighter icy surfaces and a spectrometer to detect hydrogen. Water ice was found in craters within 5° of both poles, with some smaller deposits as far as 10° out.

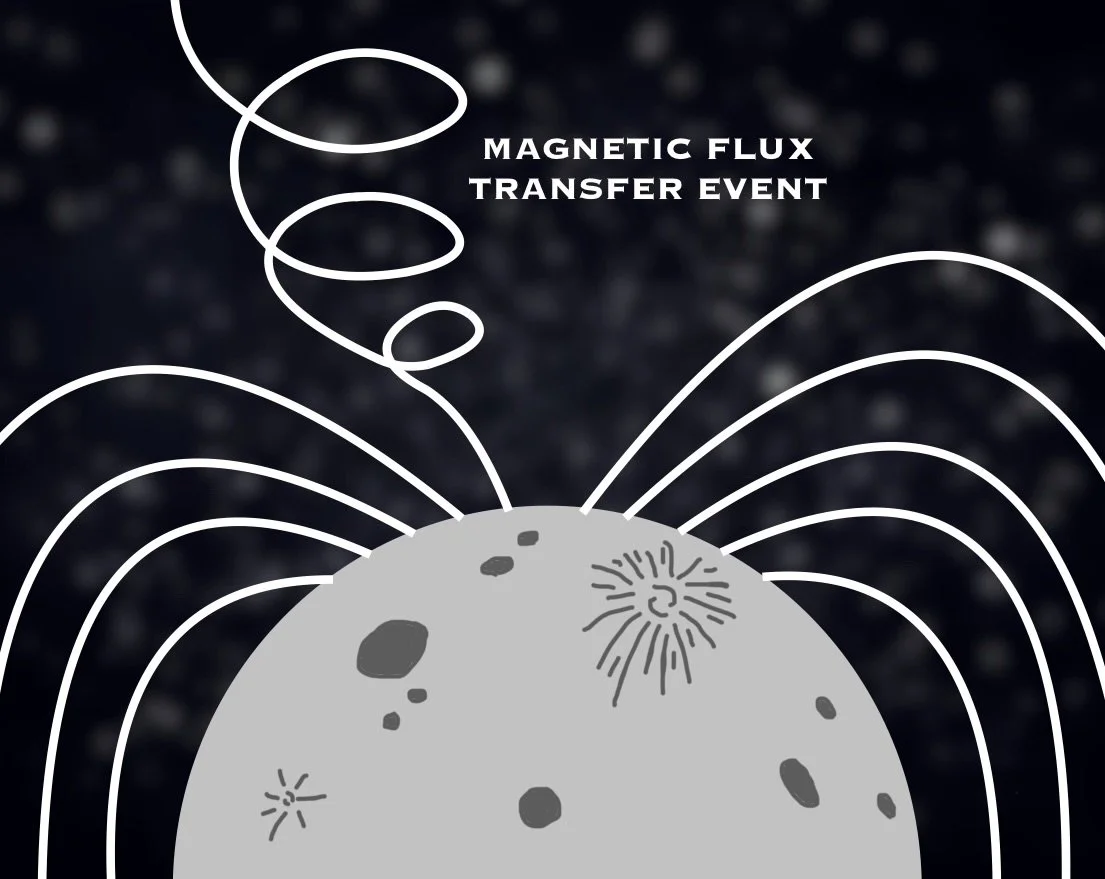

As Mercury is so close to the Sun, the solar wind is particularly punishing. So much so that it frequently twists the planet’s magnetic field up into coils, or colossal magnetic tornadoes. Scientists call these “magnetic flux transfer events.” The solar wind rides the coils of these magnetic tornadoes and slam into the surface, lifting atoms up high into the sky and then Mercury’s gravity pulls them back down. These tornadoes can sometimes be as wide as the entire planet. It is now hypothesized that these invisible magnetic storms actually feed Mercury with material for its very thin, patchy exosphere.

The Sun has also been found to create aurorae on Mercury, but not in the way we usually think. On Earth, solar wind rides the planet’s magnetic field down and collides with the atmosphere at the poles. This ionizes the atoms, generating a visible multi-colored glow in the sky. Mercury, on the other hand, barely has an atmosphere so the solar wind can reach the planet’s rocky surface unimpeded. At Mercury’s close proximity, the radiation is so powerful that it produces X-rays when it strikes the surface. These are too energetic to be seen with the naked eye and must be detected by special instruments.

Solar wind from the Sun and micro-meteorites that hit the surface, eject sodium atoms entrenched within Mercury’s soil and blast them out into space. This forms a golden tail of sodium gas that is around 24 million kilometers long.

It is only possible to see Mercury’s sodium tail for yourself under certain conditions. This requires the ability to take long exposure images and a special filter. Specifically, a 589 nanometer filter is attuned to the golden glow of sodium. Hint: The tail is brightest when Mercury is within 16 days of perihelion (when it is closest to the Sun).

In the 19th century, astronomers noticed that Mercury’s orbit behaved in ways Newtonian physics could not fully explain, particularly a small but persistent precession of its perihelion. To resolve this, mathematician Urbain Le Verrier proposed the existence of an unseen planet orbiting closer to the Sun, which became known as Vulcan. Over the following decades, multiple astronomers reported fleeting sightings of objects near the Sun, fueling confidence that Vulcan existed, yet none of these observations could be consistently verified. The mystery persisted until Albert Einstein’s general theory of relativity demonstrated that the intense curvature of spacetime near the Sun naturally accounts for Mercury’s orbital behavior, eliminating the need for an extra planet and turning Vulcan into a famous example of how scientific progress can replace a plausible hypothesis with a deeper, more accurate understanding of nature.