The Hunt For Planet Vulcan

by Sam Atkins

Throughout the late 19th and early 20th century, an anomaly in physics led astronomers to frantically scour the daylight in search of a mythic and elusive world of scorching fire. The truth ended up being stranger than any of them could have imagined.

NOTE: Tap or hover over images for captions and credits.

This story begins with a French astronomer and mathematician named Urbain Le Verrier who was very interested in celestial mechanics. He had been catapulted into worldwide fame after mathematically predicting the location of Neptune, leading to its subsequent discovery in 1846. Soon after, he would begin a project that would consume the rest of his life. The goal, as he put it, was to “embrace in a single work the entire planetary system, put everything in harmony, if possible, otherwise, declare with certainty that there are as yet unknown causes of perturbations...”

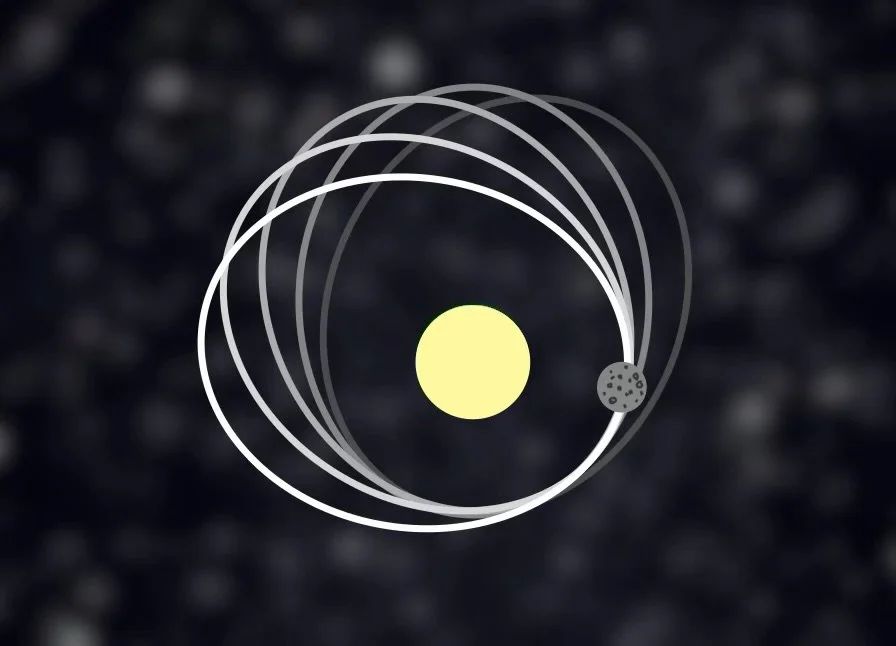

That last curious phrase is the catalyst for this story. Le Verrier had observed for some time that the orbit of Mercury was… odd. The laws of planetary motion as written by German physicist Johannes Kepler state that planets orbit the Sun, not in perfect circles, but in ellipses with the Sun placed at one of two focii. This means that when a planet revolves around the Sun, there is a point when it is furthest from the Sun (called aphelion) and revolves slowly, and a point when it is closest to the Sun (called perihelion) and revolves quickly. From this point up until the late-19th century, it was understood that the ellipse should be a perfectly repeating pattern in which the perihelion of an orbit would take place at the same spot each revolution.

It was later discovered that planets did deviate from this. Their orbits engaged in what became known as precession, in which their perihelions moved around the Sun, causing the entire orbit to rotate. Astronomers were able to quickly deduce that these precessions were caused by gravitational tugs on each planet by all others. These tugs were known as perturbations. It was perturbations from Neptune onto Uranus that originally sparked the search that would end in Le Verrier’s grand prediction. So, this must have been the cause for Mercury’s precession as well. Right?

Le Verrier found that when calculating the collective effects of perturbations from all the planets on Mercury, they did not account for the entirety of its rate of precession. Le Verrier reanalyzed timed observations of previous Mercury transits of the Sun’s disk from 1697 and 1848 that also did not agree with what celestial mechanics predicted. This led Le Verrier to ask: Was Newton wrong? Did he miss something?

Rather than toss out the last century of Newtonian physics, Le Verrier sought another explanation. Perhaps celestial mechanics were working just fine but there was a missing variable. After all, Le Verrier’s own claim to fame was the discovery of a new planet by considering its hypothetical perturbations on another. It seemed likely then that something similar was acting on Mercury: an as yet undiscovered planet.

In 1859, Le Verrier published a thorough study of Mercury’s orbit. In it, he suggested that there must have been a small planet, or perhaps a series of asteroids, that orbited closer to the Sun, and that it was that object’s gravitational influence that accounted for Mercury’s additional 43 arcseconds of precession per century.

Le Verrier received a letter while attending a New Year’s Eve party from a French amateur astronomer named Lescarbault claiming to have previously witnessed the hypothetical planet transiting across the Sun. Le Verrier visited the man in his village of Orgères-en-Beauce some 70 km southwest of Paris. Following his inquiry, Le Verrier victoriously announced that the ninth planet of the solar system had been discovered. He called it Vulcan, named after the Roman god of fire to reference its close proximity to the Sun. With two planets discovered, Le Verrier was officially the top planet hunter in the world.

Or so he thought…

There were many who remained unconvinced of Lescarbault’s discovery. A previous assistant of Le Verrier, Emmanuel Liais, had since relocated to Brazil and became the director of the Imperial Observatory in Rio de Janeiro. He claimed to have been observing the Sun at the same moment as Lescarbault (based on the time given) while using a more powerful telescope. He refuted this planet transit took place and with his superior equipment and stature, his word held more sway.

The hunt for the planet Vulcan carried on while Le Verrier continued to tune his calculation of Vulcan’s orbit to that of Mercury’s. It became common practice for both amateur and professional astronomers to search for Vulcan during solar eclipses. With the glare of the Sun blocked by the Moon, any close orbiting bodies would become visible. Along the way, there was much speculation about the characteristics of this hypothetical planet. The orbit was estimated to be nearly circular with a radius of about 21 million km. It was calculated that the planet would make a full revolution around the Sun in just under 20 days. The greatest elongation was thought to be just 8° which would make it nearly impossible to see through the Sun’s glare, even at twilight. The best hope to spot Vulcan was via a transit across the Sun’s disk of which there were expected to be two to four per year (very frequent compared to Mercury and Venus).

Between 1860 and 1877, there were several astronomers around the world who claimed to have spotted Vulcan during one of these suspected transits. Some even suggested they could see a red tint emitting from its scorching, rocky surface. Many observers brought forward claims of objects seen from years earlier and/or kept poor records of their time and date. However, even among the most advanced and organized expeditions in the world, no claims were able to hold up to scrutiny based on Le Verrier’s calculations. Whether the planet was too small to be seen or simply wasn’t there, Le Verrier would pass away in 1877 at the age of 66, having never confirmed the existence of Vulcan. Regardless, the search would continue in earnest into the 20th century. It was here that the next important figure in this story comes to light.

In 1905, German physicist Albert Einstein published his special theory of relativity. One of its key principles is that the laws of physics are the same in all inertial reference frames, meaning for all observers moving at constant velocities relative to one another. A striking consequence of this is time dilation. A clock moving relative to an observer appears to run more slowly than one at rest with respect to that observer.

Ten years later, in 1915, Einstein published his general theory of relativity, which expanded his principles of special relativity to include gravity. Unlike Newton, who described gravity as an instantaneous force acting between masses, Einstein proposed that gravity arises from the curvature of spacetime. Let’s use a simplified analogy. Imagine space as a two-dimensional elastic fabric, then place a sphere at the center. The weight of the sphere causes it to sink into the fabric, creating a depression that guides the motion of other objects around it. Smaller objects no longer need to be pulled around the sphere by a distant force. Instead, they simply move forward freely, following the curved geometry of the depression. This straightest possible path through curved spacetime is known as a geodesic.

“Matter tells spacetime how to curve; spacetime tells matter how to move.”

John Archibald Wheeler

As strange as these new ideas were, they inspired astronomers and mathematicians to revisit the curious precession of Mercury with fresh eyes. Einstein’s equations of general relativity provided exactly the missing piece that Le Verrier had been searching for. When applied to Mercury’s orbit, they revealed that spacetime near the Sun is so strongly curved that the planet’s path does not close on itself in a perfect ellipse. Instead, with each revolution, Mercury overshoots slightly, causing its perihelion to advance. The extra curvature accounted precisely for the unexplained 43 arcseconds per century that Newtonian physics and the hypothetical planet Vulcan could not. Astronomers soon realized that this relativistic correction applied to the precession of all planetary orbits. But because Mercury lies closest to the Sun where spacetime is curved the most, the effect is far more pronounced there than anywhere else.

This mystery served as the first major test of general relativity and it passed with flying colors. It perfectly synthesized how the advancement of scientific understanding, like relatively, does not always happen in a straight line. To be clear, Einstein’s relativity does not disprove or replace Newtonian mechanics. Even as an approximation, Newton’s law of universal gravitation remains extraordinarily accurate in most circumstances: tracking the orbits of planets, predicting eclipses, and launching rockets into space. It is applicable to objects moving in weak gravitational fields and well below the speed of light. Once you start reaching those extremes, relativity becomes much more important. The two combine to create a broader, more complete framework.

While Vulcan was never found, the concept captured the imagination of both scientists and the public. It also contributed to the development of modern astrophysics and the understanding of orbital mechanics. In popular culture, Vulcan has been referenced in various science fiction works, most notably in the "Star Trek" franchise, where it is the home planet of Spock and other Vulcans. The International Astronomical Union still has the name Vulcan reserved for the discredited hypothetical planet. Vulcanoids as well. What Le Verrier thought was hidden in the Sun’s glare turned out to be hidden in the fabric of the cosmos itself. Yet Vulcan is forever immortalized, not as a planet, but as a landmark in humanity’s enduring quest to understand the universe.