New Horizons

by Sam Atkins

Twenty years after its launch, New Horizons remains the only spacecraft to visit the dwarf planet, Pluto, as well as numerous other trans-Neptunian objects. It’s also one of the most distant human-made objects from Earth. Let’s follow this spacecraft’s journey and discover how it transformed Pluto from a distant, pixelated blob into one of the most beautiful and diverse worlds ever captured in high-resolution.

NOTE: Tap or hover over images for captions and credits.

The New Frontiers Program

Following a drought of missions in the 1980’s, NASA Administrator Daniel Goldin adopted what would become a rather infamous philosophy: “faster, better, cheaper.” It has long been said that you can only ever hope to have two of those, never all three. Goldin sought to accomplish this by focusing NASA’s efforts throughout the 1990’s on more frequent, smaller-scale, inexpensive missions like Mars Pathfinder. However, many of these missions ended in failure or cancellation due to cost overruns, scheduling issues and design flaws.

Behind the scenes, there was a real hunger to once again pursue larger, more ambitious missions like the Cassini probe sent to Saturn in 1997. Go big or go home. This was exemplified by Project Prometheus which sought to develop advanced nuclear-powered spacecraft like the Jupiter Icy Moons Orbiter (JUICE). Others were insistent that these more complex projects were politically fragile and lean science missions were still viable. The New Frontiers program emerged as a deliberate middle ground. Projects needed to answer major scientific questions while remaining affordable and repeatable. But what would be the target of such missions?

There was always a desire to visit the mysterious ninth planet of our solar system. Pluto is so small and distant that even Hubble struggles to resolve any detail from Earth’s orbit. However, Pluto was routinely overshadowed by targets like Mars and Europa which were much closer to home and made very alluring promises of astrobiological discovery. On the other hand, there was some sense of urgency regarding the suspected collapse of Pluto’s atmosphere as it crawled further from the Sun. It was believed that the gas would eventually freeze onto the surface, robbing us of an opportunity to study it. In keeping with New Frontier’s middle ground philosophy, it was settled that a focused, fast, chemically-propelled flyby could be built within a cost cap. Thus, the first mission of the program was born: New Horizons.

The New Horizons Space Probe

The New Horizons space probe was designed under an unusual regime of constraints. Its propulsion, electrical and data-mining power is quite limited, and Pluto was more distant than any object yet visited in the solar system. New Horizons needed to be very fast, light, autonomous and incredible efficient with how it used its power.

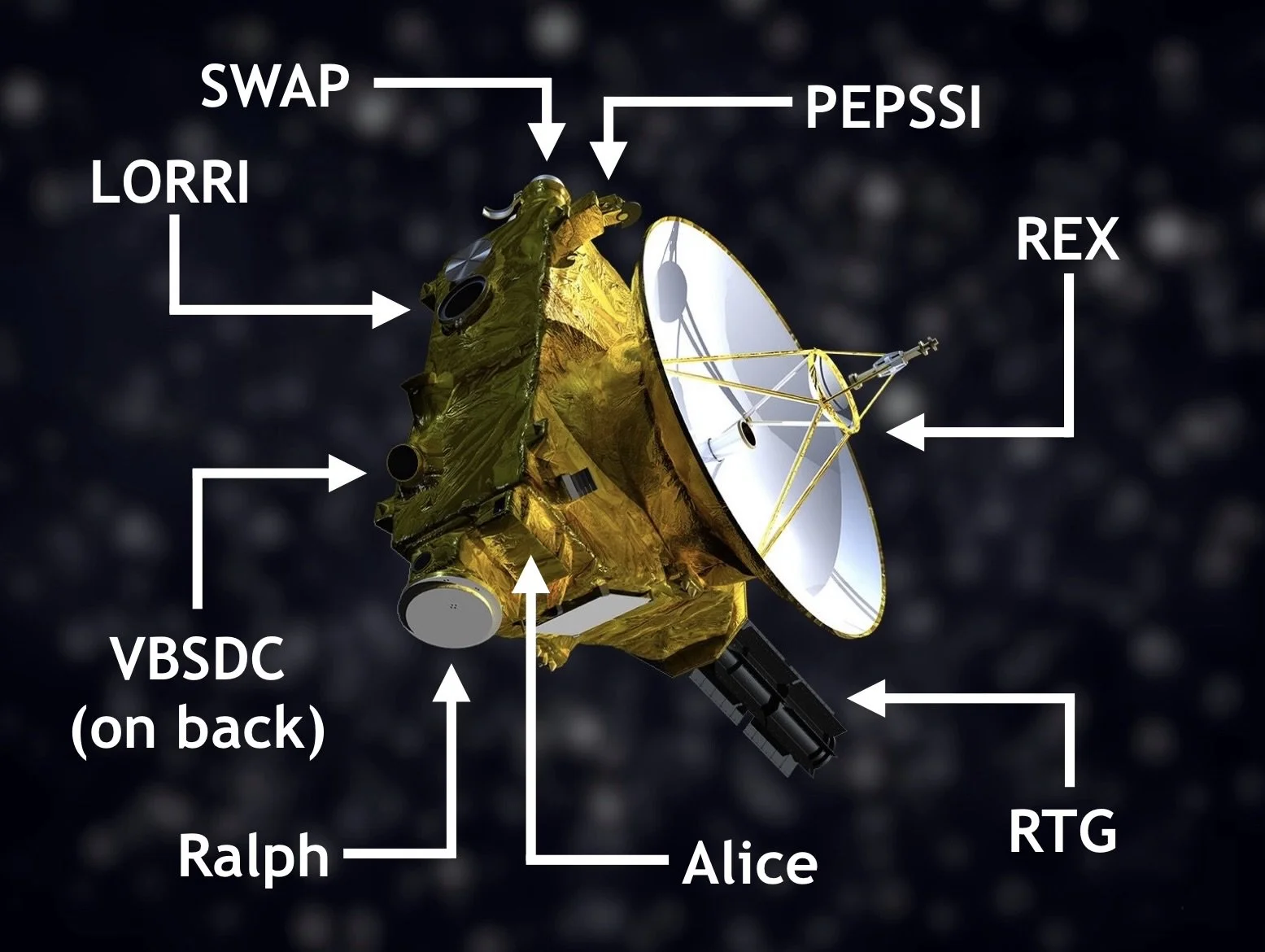

About the size and shape of a satellite dish strapped to a grand piano, New Horizons’ triangular body is wrapped in layers of golden film-like material that act as insulation to protect its delicate instruments from the extreme temperatures of space, both hot and cold. It weighs almost half a ton when fully fueled.

It was launched from Earth at incredible speed and has spent the vast majority of its journey coasting via inertia. Its path is directed primarily by the gravity of the Sun and planets. It does have a basic propulsion system consisting of eight small hydrazine-propellant thrusters (and an additional eight for back-up) mounted across the spacecraft in different locations. These allow the spacecraft to spin and reorient itself precisely to make corrections to its trajectory or aim its science instruments.

New Horizons is powered by a radioisotope thermoelectric generator (RTG), a nuclear battery that uses the natural decay of plutonium to generate lots of heat. That heat is then converted directly into electrical power by thermocouples. It’s surprisingly simple as far as nuclear technology goes and can last significant periods of time. The power generated goes to New Horizons’ various antennae, thrusters and, most important of all, its seven science instruments.

📡 Radio Science Experiment (REX)

New Horizons’ most eye-catching feature is its large high-gain dish antenna, which primarily communicates data back to Earth. It also serves as a science instrument: the REX experiment used radio signals passing through Pluto’s atmosphere to measure temperature and pressure, and to precisely determine the mass and diameter of Pluto and its moons.

📷 Ralph

New Horizons’ main visible and infrared imager, essentially its “eyes.” Ralph captured detailed color images and mapped surface features of Pluto, Charon, and Arrokoth. Ralph also analyzed surface compositions by detecting variations in reflected sunlight across visible and infrared wavelengths.

🔬 Alice

New Horizons’ ultraviolet imaging spectrometer. Alice measured the composition and structure of Pluto’s and Charon’s atmospheres by detecting how ultraviolet sunlight is absorbed and scattered. This allowed scientists to identify gases like nitrogen and methane and study how the atmosphere thins into space.

🔭 Long Range Reconnaissance Imagery (LORRI)

A high-resolution telescopic camera designed to snap sharp black-and-white images from great distances. LORRI provided detailed views of Pluto and its moons, revealing surface features like craters, mountains, and plains that were too small to see with other instruments.

☀️ Solar Wind Around Pluto (SWAP)

SWAP measures how Pluto’s atmosphere is shaped, or even eroded, by the flow of charged particles from the Sun’s solar wind.

⚡️ Pluto Energetic Particle Spectrometer Science Investigation (PEPSSI)

PEPSSI detects energetic ions and electrons escaping from Pluto’s atmosphere. By measuring the speed, density, and types of these particles, it helps scientists understand how Pluto’s atmosphere is slowly leaking into space and how it interacts with the surrounding plasma environment.

✨ Venetia Burney Student Dust Counter (VBSDC)

The VBSDC was by students at the University of Colorado Boulder and later named after the girl who named Pluto. It consists of detector panels mounted to the face of the space probe (the side facing in its direction of movement and opposite the Sun). As New Horizons cruises through space, pieces of dust that impact the panel generate an electrical charge. The detector records the distribution of interplanetary dust and measures individual dust particle’s size, mass, velocity and spectra.

All the data from these detectors and imagers are converted into binary code by the space probe’s onboard computer systems. These 1’s and 0’s are then modulated onto radio waves. The curve of the 2.1 meter-wide, high-gain antenna dish mounted to the front of the spacecraft focuses those modulated radio signals into a narrow beam pointed precisely at Earth. Back home, a worldwide network of huge radio dishes intercepts those radio signals and reconvert their modulations back into the original data for scientists to interpret. Sometimes when New Horizons must spin or adjusting its instruments, this precision aiming can’t be done. In this situation, the space probe’s onboard computer relies on its three smaller antennae which send out broader, slower signals to cover the gaps.

Launch

January 19th, 2006

On a beautiful January afternoon, the rocket carrying the New Horizons space probe stood poised on the launch pad at Cape Canaveral, Florida. The sky was a beautiful blue with only a few scattered clouds, and the temperature was a comfortable 70°F. After a few previous attempts were thwarted by storms and high winds, the weather was finally perfect for launch.

At 2:00pm, the rocket’s thrusters roared, billowing out a torrent of flames and smoke before lifting up into the sky. Carried aboard the New Horizons space probe are the ashes of Clyde Tombaugh, the American astronomer who discovered Pluto back in 1930. Now, he was on a one-way trip to visit that planet and continue on into the cosmos beyond. A fitting tribute to his legacy.

The Atlas V rocket climbed into the heavens, burning each of its three stages, one after the other, before dumping them. About 45 minutes after launch, New Horizons had reached an incredible speed of 58,000 km/h, an escape velocity from not only Earth, but the Sun. It is the fifth spacecraft to reach this speed but the first to reach this speed during launch from Earth.

Freed from all stages of the Atlas V rocket, the space probe was soaring into the cosmos and began its long cruise to Pluto. By 11:00pm (just nine hours after launch), New Horizons crossed the lunar orbit, passing within 183,000 km of the Moon (about half the distance to Earth). For comparison, it took the Apollo 11 crew about three days to reach this distance. It would be just over a year before it would reach Jupiter. In the meantime, a few interesting things happened.

Asteroid 132524 APL

June 13th, 2006

As it crossed through the main asteroid belt, New Horizons happened to pass pretty close to 132524 APL, a small asteroid discovered from Earth back in 2002. This was not planned, but a fortuitous encounter. New Horizons had yet to even activate all its science instruments. This included LORRI, the probe’s highest magnification imager, which was unfortunate. However, New Horizons’ 75mm main imager, Ralph, was operational and NASA’s not one to let an opportunity pass by unexplored. It was also a chance for the mission team to calibrate New Horizon’s instruments and practice tracking objects.

With New Horizon’s images, it was able to confirm the asteroid’s stony composition previously determined via spectral analysis. It was also able to confirm the asteroid’s 2.5 km diameter (about twice the length of the Golden Gate Bridge’s main span).

A funny thing happened on the way to Pluto…

August 24th, 2006

About seven months after the New Horizons space probe was set on its path to Pluto, the ninth planet was a planet no more. Following a week of deliberation, the International Astronomical Union voted in favor of reclassifying Pluto as a dwarf planet. This remains controversial to this day amongst both astronomers and the public being that Pluto had been a part of the solar system’s planetary family for 76 years.

The decision was reached on the grounds of how we define what a planet is. The IAU determined three criteria:

The object must orbit the Sun.

The object must be massive enough to achieve a near-spherical shape.

The object must “clear its neighborhood” around its orbit.

It is that last one that got Pluto wiped off the board. The former-planet revolves around the Sun in an incredibly eccentric and inclined orbit compared to the eight proper planets. It also shares its orbit with the Kuiper belt, a vast region of icy objects beyond Neptune’s orbit. Kind of like a much larger, frozen asteroid belt. Pluto is the largest known trans-Neptunian object but surely less massive than the combined mass of the icy bodies in its path. It’s also quite small compared to planetary bodies within Neptune’s orbit. For example, Pluto is just 0.04% the mass of Mercury and even 18% the mass of Earth’s Moon. For these reasons, Pluto was determined not to be the dominant presence in its orbit.

Despite some hard feelings, Pluto is still the same object we’ve always loved but we’d yet to truly know. With New Horizons still on its way, we would learn more about it with one flyby than all previous decades of Earth observations combined.

Jupiter flyby

February 28th, 2007

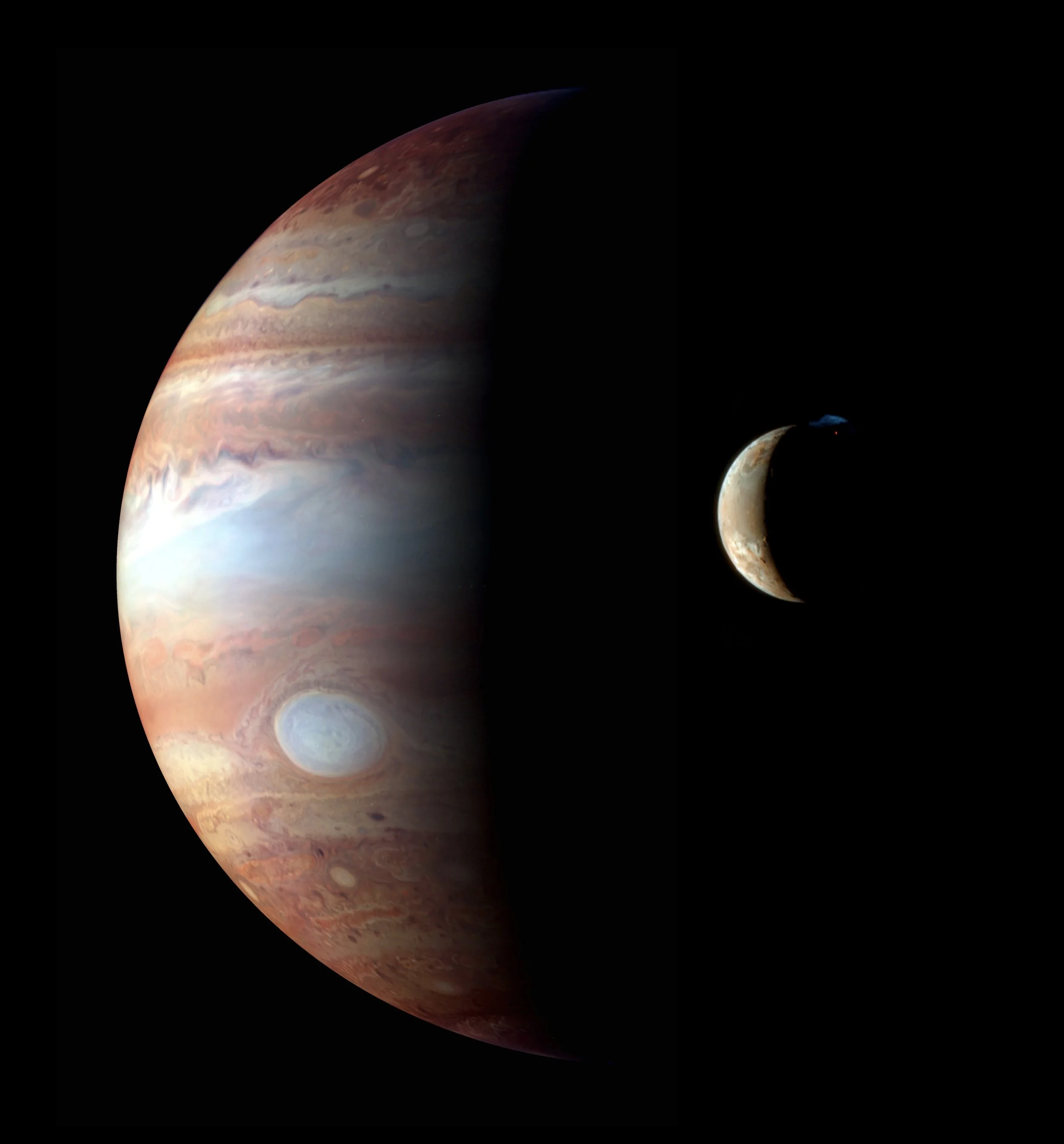

With Pluto so far away, New Horizons was looking at a potentially very long journey. That’s why NASA planned for it to visit Jupiter along the way. The most massive planet in our solar system has the most powerful gravity. These gravitational fields are some of the most efficient speed boosters available in modern space exploration.

As New Horizons approached Jupiter, the planet’s gravity began to pull the probe towards it, greatly increasing its speed and bending its trajectory. These maneuvers are known as gravity assists and allow spacecraft to navigate the solar system relatively quickly without requiring tons of extra fuel. This particular gravity assist increased New Horizons’ speed to 83,000 km/h (relative to the Sun), making it the fastest man-made object ever up to that point and shortened its journey to Pluto by three years.

At its closest, New Horizons passed within 2.3 million km of Jupiter. This was the midpoint of a four-month observation campaign (January to June). New Horizons used its full suite of state-of-the-art instruments and cameras to make more than 700 separate observations of Jupiter and its four largest moons. This would also serve as a dress rehearsal for the space probe’s later flyby with Pluto.

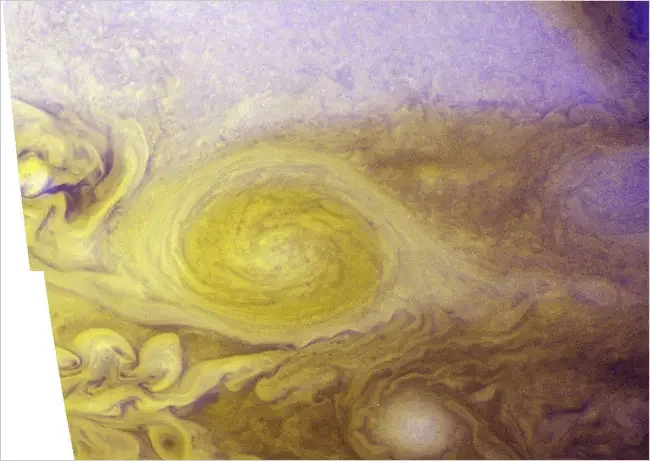

During its observation, New Horizons studied Jupiter’s powerful storms, including the closest views of the planet’s Little Red Spot, a smaller version of the Great Red Spot (but still 70% the diameter of Earth). This storm formed when three smaller white storms merged back in 2000. The year before New Horizons’ arrival, it mysteriously turned from white to red. It is unclear why this color change occurred. Two images taken 30 minutes apart confirmed that the storm churned much faster than its three precursors. Some speculate that this faster speed pulled up deeper gases that were either red themselves or changed to red upon being exposed to sunlight.

New Horizons also observed other interesting phenomena such as clouds forming from ammonia welling up from the lower atmosphere as well as heat-induced lightning near Jupiter’s poles.

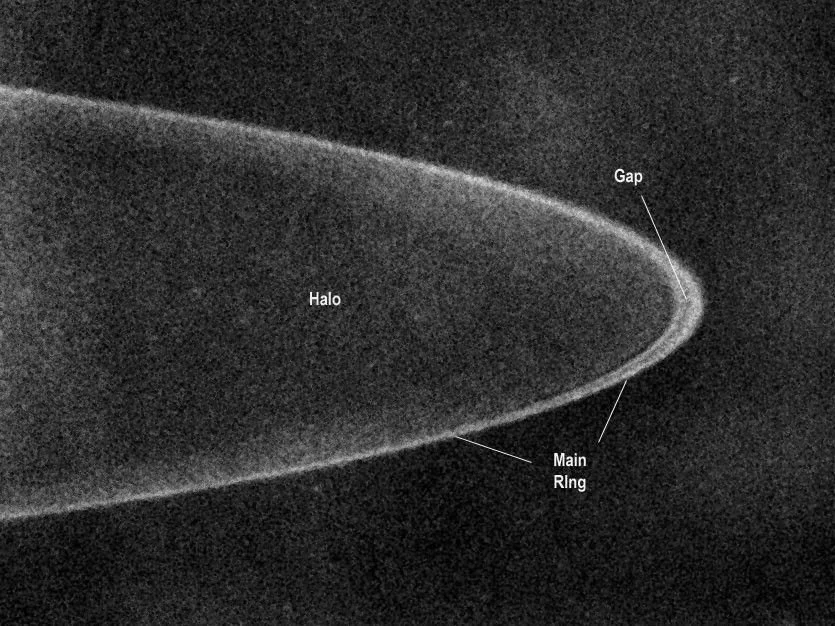

It also took detailed images of Jupiter’s faint ring system that was first discovered in 1979 by the Voyager probes. New Horizons’ LORRI instrument revealed distinct lanes of gravel-sized particles in the main ring and a dusty halo that extends inward towards the planet. It was determined from these images that Jupiter’s rings developed from the dust and debris left over from small, broken-up inner moons and shepherded by Jupiter’s gravity.

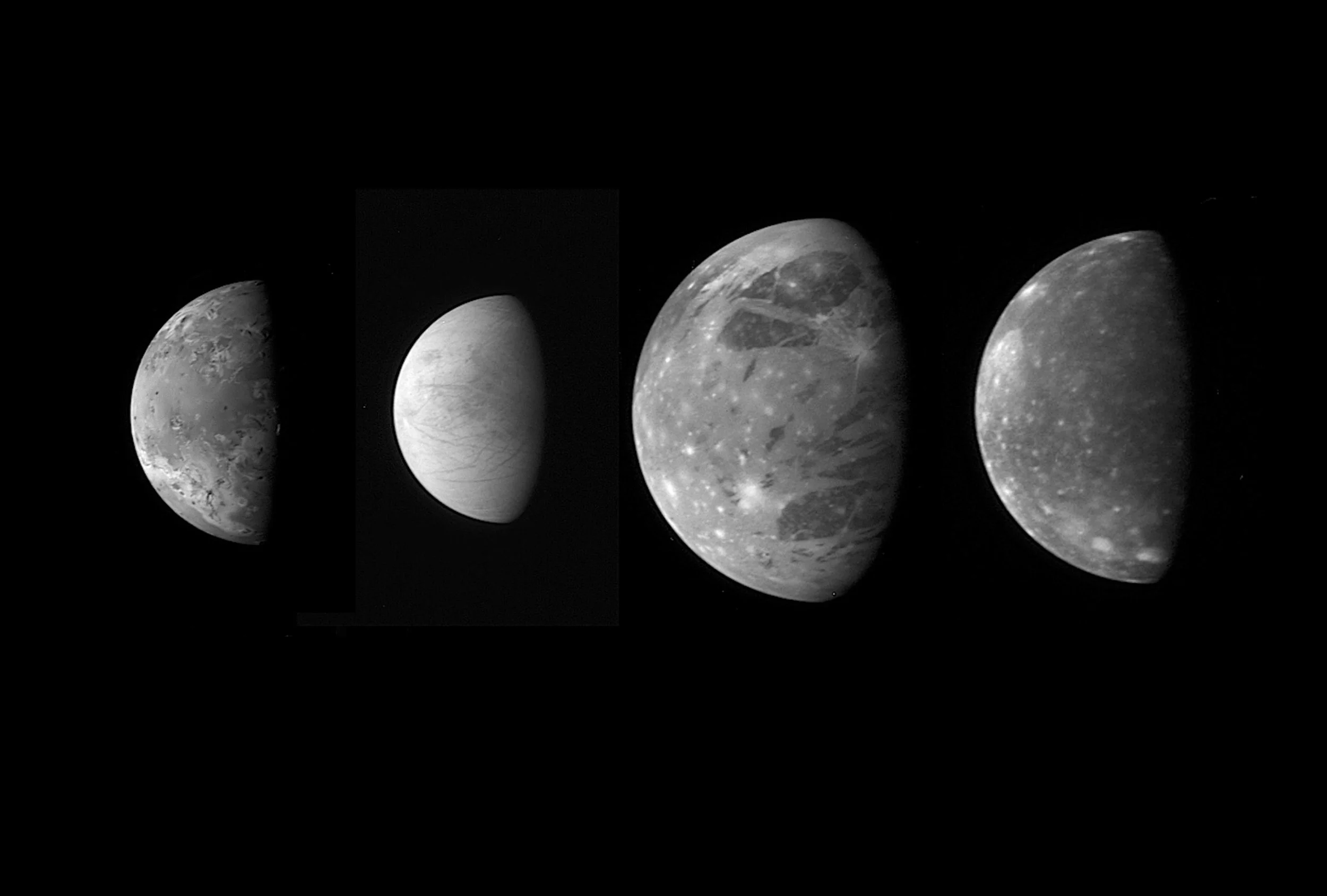

New Horizons also captured images of each of Jupiter’s four largest moons, but the biggest focus was on Io. This moon is well-known for its volcanism and bizarre appearance. It’s the most volcanically active body in the solar system. New Horizons observed eleven different volcanic plumes, three of which were discovered for the first time, blasting tons of sulfur and sulfur dioxide into space and becoming ionized and trapped by Jupiter’s magnetosphere. One eruption in particular was seen rising hundreds of kilometers above the volcano Tvashtar, giving us a unique opportunity to study the plume’s structure and motion.

Outer solar system

2007 — 2015

With Jupiter receding as a crescent shape into the glare of the Sun, New Horizons had nothing left between it and Pluto. Yet it still had most of its journey ahead, with 26.3 AU remaining (Astronomical Units are the average distance between the Sun and Earth).

Four months after its Jupiter flyby, New Horizons was placed into hibernation mode with redundant components, guidance and control systems powered off. This would save operation costs as well as minimize wear and tear on the electronics. It also freed up the Deep Space Network back on Earth to track other ongoing missions. About once a year, New Horizons would be activated for a few months to calibrate its instruments and perform systems checks. Upon activation in July 2013, New Horizons even managed to resolve Pluto and its largest moon, Charon, as distinct points of light and observed them revolving around each other.

Ultimately, it would spend over seven years in and out of an electronic sleep. On December 7th, 2014, New Horizons was woken from hibernation with 260 million km (about 1.7 AU) and six months remaining. New Horizons began preliminary observations of Pluto on January 4th, 2015.

Pluto flyby

July 14th, 2015

The day everybody had waited nine-and-a-half years for was finally upon them. As soon as July 14th began, Pluto was about as far from New Horizons as the Moon is from Earth. The space probe closed in on the dwarf planet coasting at a quick 50,000 km/h. During this time, New Horizons was programmed to automatically follow a scripted sequence of commands. The planned observation and imaging of the Plutonian system required 22 hours of radio silence. All the mission team could do was wait.

New Horizons made its closest pass of Pluto at just 12,472 km away (about the width of Earth). At this distance, Pluto would have appeared 11° across, or twenty-two full moons wide.

This video shows the New Horizons’ July 14th flyby of the Plutonian system (sped up to 5 minutes per second). Video credit: NASA’s Eyes on the Solar System

New Horizons’ science objectives were organized into three tiers of priority.

Its primary objectives were required. These included mapping the surface of Pluto and Charon, including their morphology (what it looks like) chemical composition (what it’s made of), as well as studying the nature of Pluto’s atmosphere, including its chemical composition, density and escape rate (due to Pluto’s weak gravity).

The secondary objectives were expected but not demanded. They were largely meant to bolster the data gathered from the primary objectives. This included studying how the surface and atmosphere changed over time, getting high-resolution images of specific regions from different angles to develop a detailed three-dimensional view, mapping surface temperatures across Pluto and Charon, and searching for any kind of atmosphere on Charon.

The tertiary objectives were to be the nice cherry on top, if time allowed for it. This included studying how energetic particles from the solar wind interact with Pluto and Charon, nail down concrete parameters of the objects such as size, mass, density, orbital path and gravity.

This unbelievable natural-color image of Pluto was taken from a distance of about 35,000 km (about three times the width of Earth). It’s a stark contrast from the blurry pixelated blob we’d always known from Hubble’s images. Using data from New Horizons’ Multispectral Visible Imaging Camera (MVIC), the colors are calibrated to approximate how Pluto would look to the human eye.

You’ll notice right away that Pluto has a richly diverse surface of colors and textures, easily the most surprising thing to astronomers. Its color palette ranges from pale tans to light yellows to deeper rust tones. These are indicative of the different surface ices and organic materials (more on that shortly).

Your eye is almost immediately drawn to the iconic heart-shaped region at the southeast that spans 1,600 km across. This is known as Tombaugh Regio (named after Pluto’s discoverer). The left lobe of the heart in particular stands out as a bright, smooth plain of nitrogen and methane ice, known as Sputnik Planitia (named after the first satellite launched into space).

To the southwest, you’ll find a region starkly contrasted against the rest of the surface: a dark reddish-brown landscape stretching nearly 3,000 km, covered in mountains and craters. It was originally dubbed Cthulhu Macula but was later officially named Belton Regio after the American astronomer. The region’s dark complexion is thought to come from a coating of organic molecules called tholins. These complex hydrocarbons have only been found on icy bodies in the outer solar system, the products of solar radiation breaking apart simple ices like nitrogen and methane into a reddish tar-like layer. There is a similar region to the east of Tombaugh Regio just barely peaking from the shadows called the “Brass Knuckles.”

Pluto’s northern polar region is equally unique. Due to the dwarf planet’s 120° axial tilt, the region has been bathed in perpetual sunlight for decades. Astronomers have noted a resemblance between Pluto’s northern latitudes and the surface of Triton, Neptune’s largest moon, with solid slabs of transparent nitrogen ice mixed with methane ice dominating the terrain. This area is characterized by yellow hues coating the dissected plateaus above and bluish-grey tones settled within the wide canyons carved between them. The surface here is heavily cratered, preserving a record of numerous impacts largely unchanged by time. It is almost certainly one of Pluto’s oldest and least resurfaced regions.

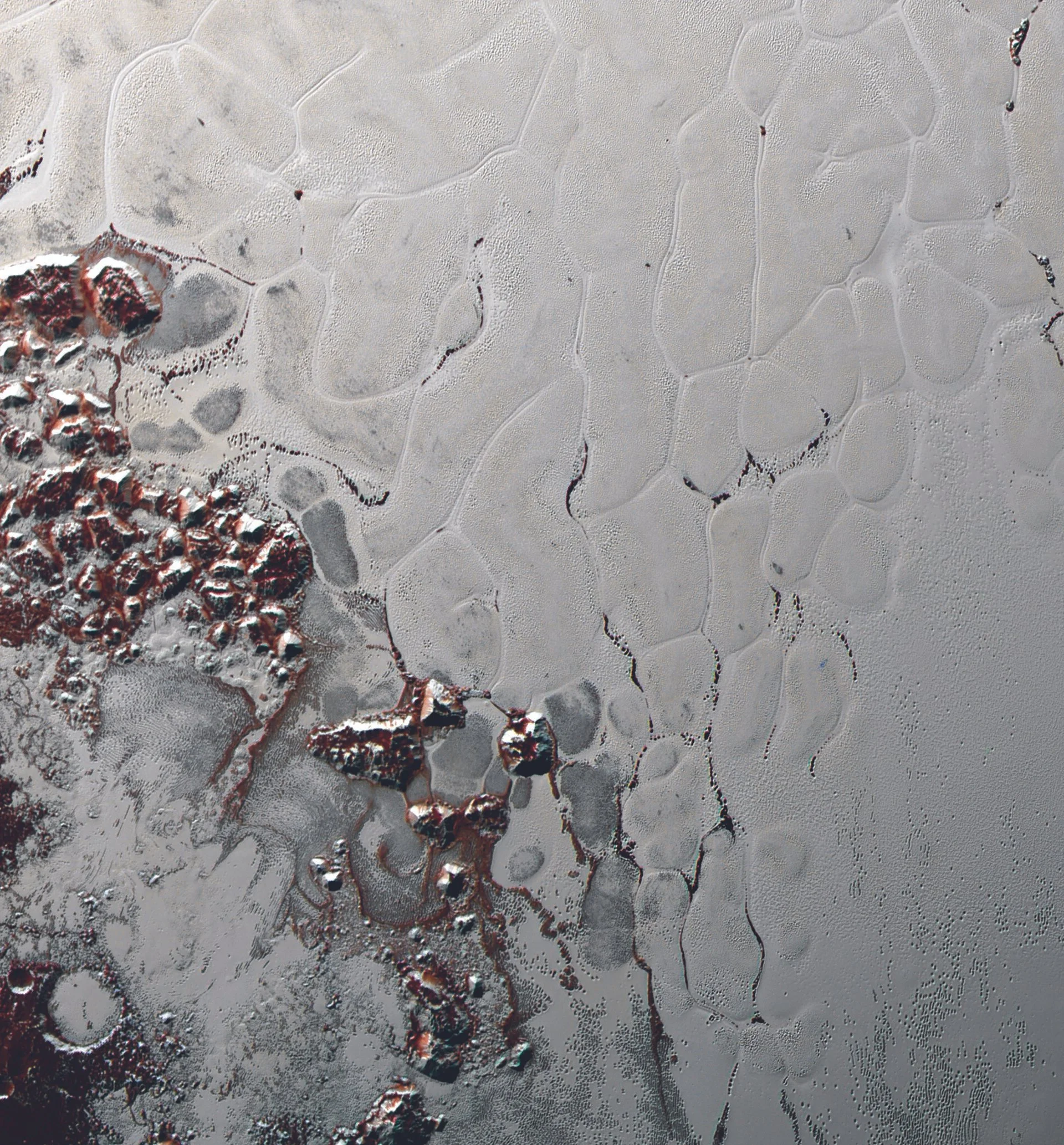

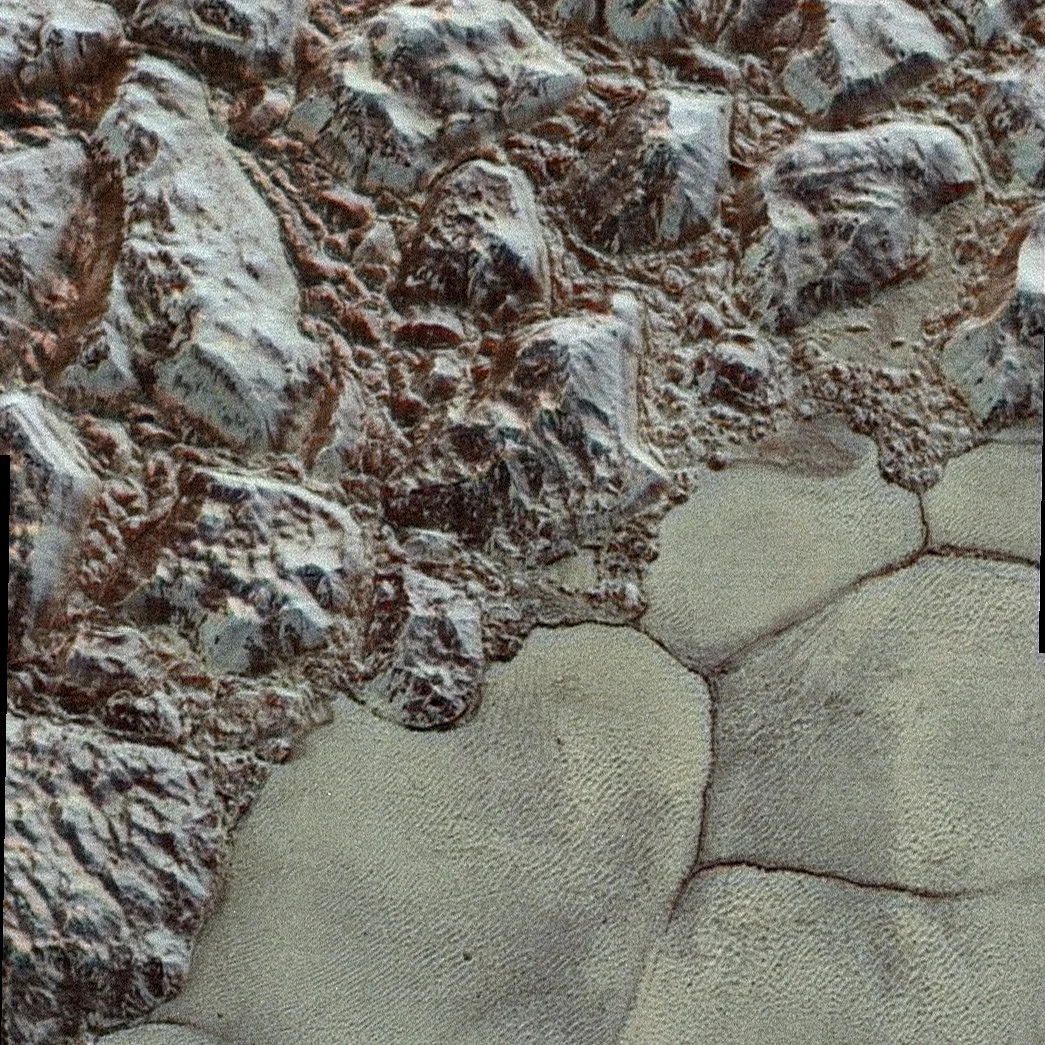

As New Horizons made its closest pass to Pluto, it used LORRI to capture surreal, high-magnification images of the dwarf planet’s surface. This enhanced-color image in particular reveals the nature of Pluto’s most iconic feature. At the southwestern edge of Sputnik Planitia, the western lobe of Tombaugh Regio, we see a remarkable phenomenon at work.

Across the northeastern half of the image lie cell-like patterns etched into a vast, white plain of nitrogen ice. These cells form through slow convection: warmer, softer ice rises at their centers, while cooler, denser ice sinks along their boundaries. A similar phenomenon occurs on the surface of the Sun, where granules churn in scorching plasma rather than frozen ice. On Sputnik Planitia, this convective motion is estimated to occur at rates of only a few centimeters per year; as fast as your fingernails grow. This provides clear evidence that Pluto remains geologically active, despite its great distance from the Sun and its limited internal heat.

To the southwest, a scattered mountain range borders the icy plains, known as Hillary Montes. Its peaks rise to heights of about 3.5 kilometers. The range is named in honor of New Zealand mountaineer Sir Edmund Hillary, who, together with his Nepalese guide, Tenzing Norgay, became one of the first climbers to reach the summit of Mount Everest in 1953.

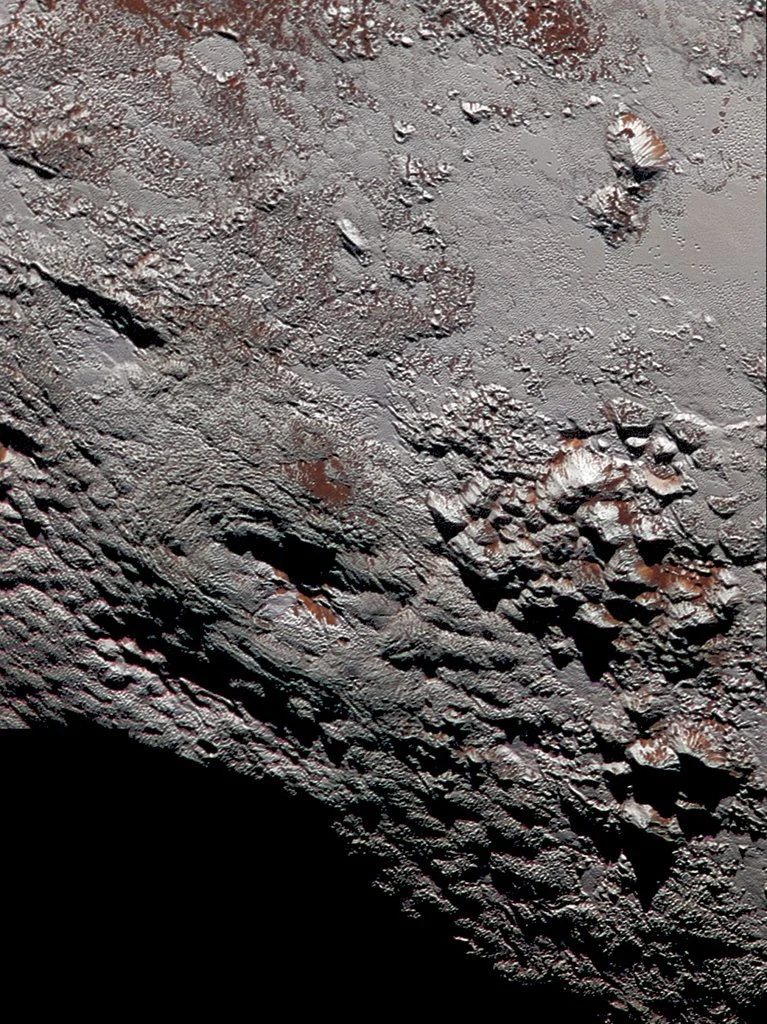

This area lies just south of Hillary Montes, deeper into the surrounding mountains that border Sputnik Planitia. On Earth, we think of mountains as giant piles of solid rock. On Pluto, mountains are made of water ice. That’s right. They are made of the same stuff as the ice cubes you put in your beverages. However, this water ice is extremely cold and dense, allowing it to be as hard and rigid as rock. Astronomers believe that these mountains were formed by cryovolcanoes belching out icy material from the dwarf planet’s mantle.

At the center right, we find a distinctive cluster of tall mountains called Tenzing Montes, named after the aforementioned Nepalese guide. The highest peak here reaches 6.2 km high, about twice the height of Hillary Montes. For comparison, Mount Everest in Nepal reaches only 4.6 km.

This image shows the northwestern edge of Sputnik Planitia at a resolution of 80 meters per pixel, spanning roughly 80 kilometers. Much like the region near Hillary Montes, convection cells border a nearby mountain range.

In the southeastern half of the image, a striking new feature appears in the nitrogen ice field, resembling fingerprints. These patterns are actually dunes, thought to have formed from windswept grains of methane ice. This is surprising given Pluto’s extremely thin atmosphere, with a surface pressure only about 0.001% that of Earth’s, which would normally suggest very weak winds. Astronomers speculate that the sublimation cycle within Sputnik Planitia, driven by nitrogen-ice convection, may help generate these features.

The al-Idrisi Montes range occupies the northwestern half of the image, ending abruptly at the edge of Sputnik Planitia and creating a sharp boundary between the two regions. The mountains look as though Pluto’s icy crust was fractured and then forced back together. Along their slopes, faint streaks run downward, hinting at ongoing surface processes.

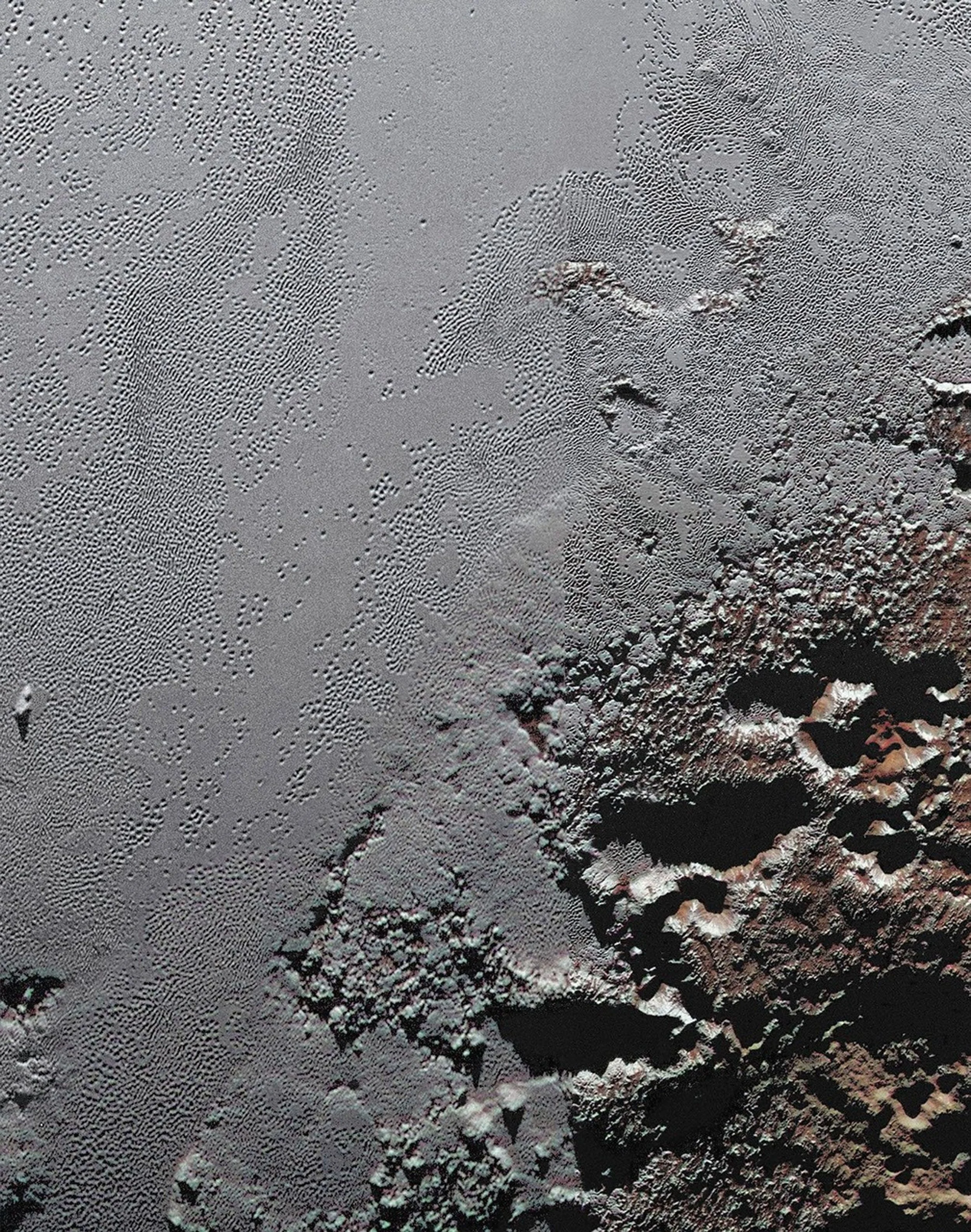

As we move across the nitrogen ice planes of Sputnik Planitia, we come to the southeastern edge to spy some unique geological features. Most interesting here are the swarms of pits scattered throughout the icy fields in the northwestern half of the image. Many of these pits are hundreds of meters wide and tens of meters deep while some of the largest can be a few kilometers wide. These pits actually resemble ones observed at the polar ice caps of Mars.

Astronomers suspect these pits are the result of sublimation. This is when a solid transforms directly into a gas (such as with dry ice). In this case, Pluto’s extreme axial tilt has placed these ice plains into prolonged sunlight through much of Pluto’s rotation (lasts six-and-a-half Earth days). This summer heat gradually warms the nitrogen ice, but because Pluto’s atmosphere is so thin, there isn’t enough air pressure for nitrogen to maintain a liquid state. Thus, it changes directly into vapor and floats up into the atmosphere.

But why pits? Why are they found in clusters with large circulation patterns? Sublimation can be very sensitive to tiny differences in the ice, from grain size to contamination by compounds like methane. The patterns of the pits could follow some kind of convection flow under the surface or could be related to the direction of sunlight. It’s largely a mystery that scientists are still investigating.

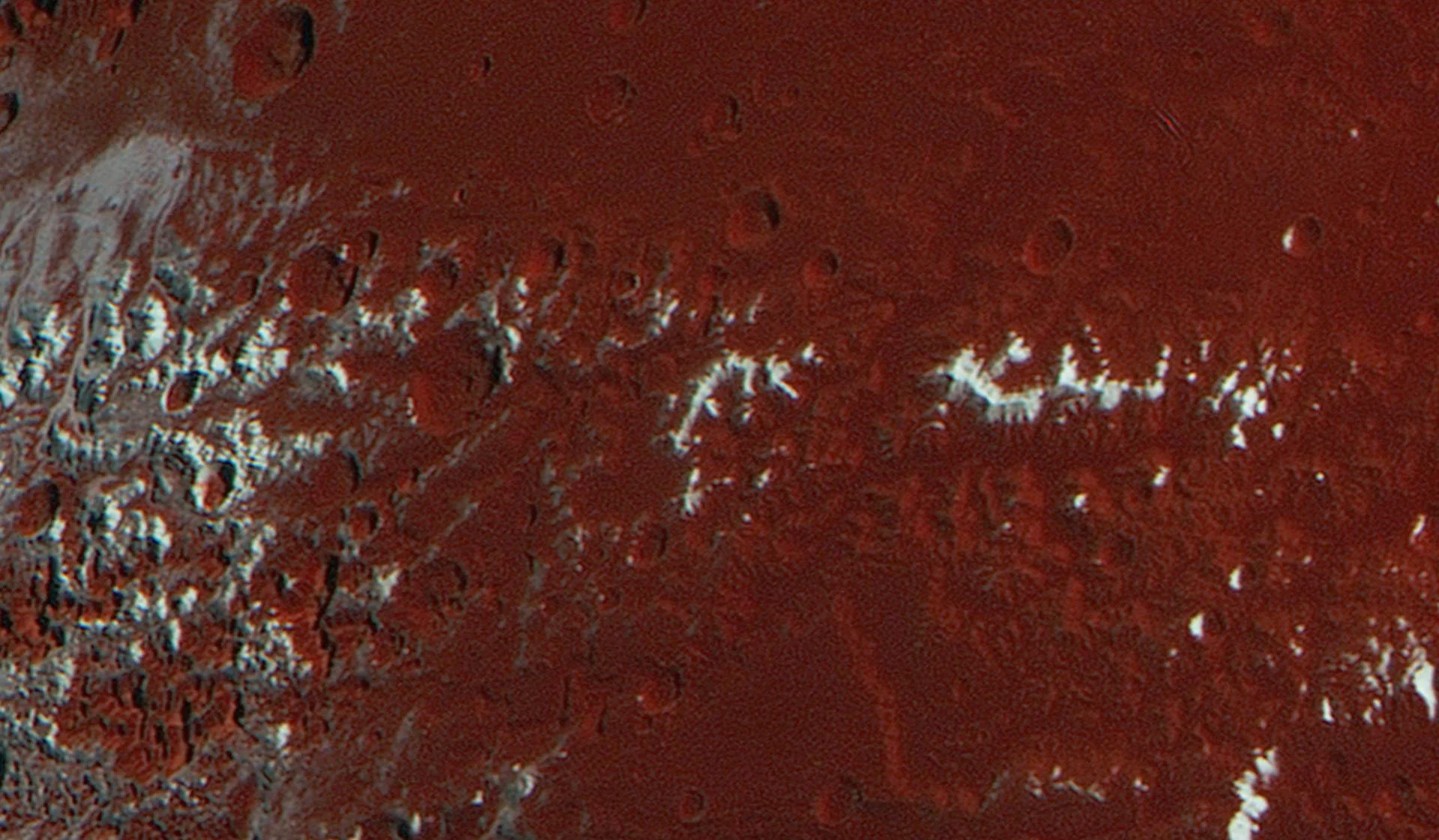

Here, we leave the bright white plains of Sputnik Planitia and head far west to the dark highlands of Belton Regio (formerly “Cthulhu Macula”). This region stretches halfway around Pluto’s equator, contrasting itself against the surrounding smooth, bright regions. The most obvious differences here are the brown-red color and the mountainous cratered terrain.

We’ve already discussed that the dark color is derived from an abundance of tholins, which form when methane and nitrogen in the atmosphere interact with ultraviolet light from the Sun. what’s interesting here are the bright white patches capping the mountains. Spectral imaging reveals this to be methane that condensed as frost onto the peaks from Pluto’s atmosphere, just like water does on Earth’s mountains.

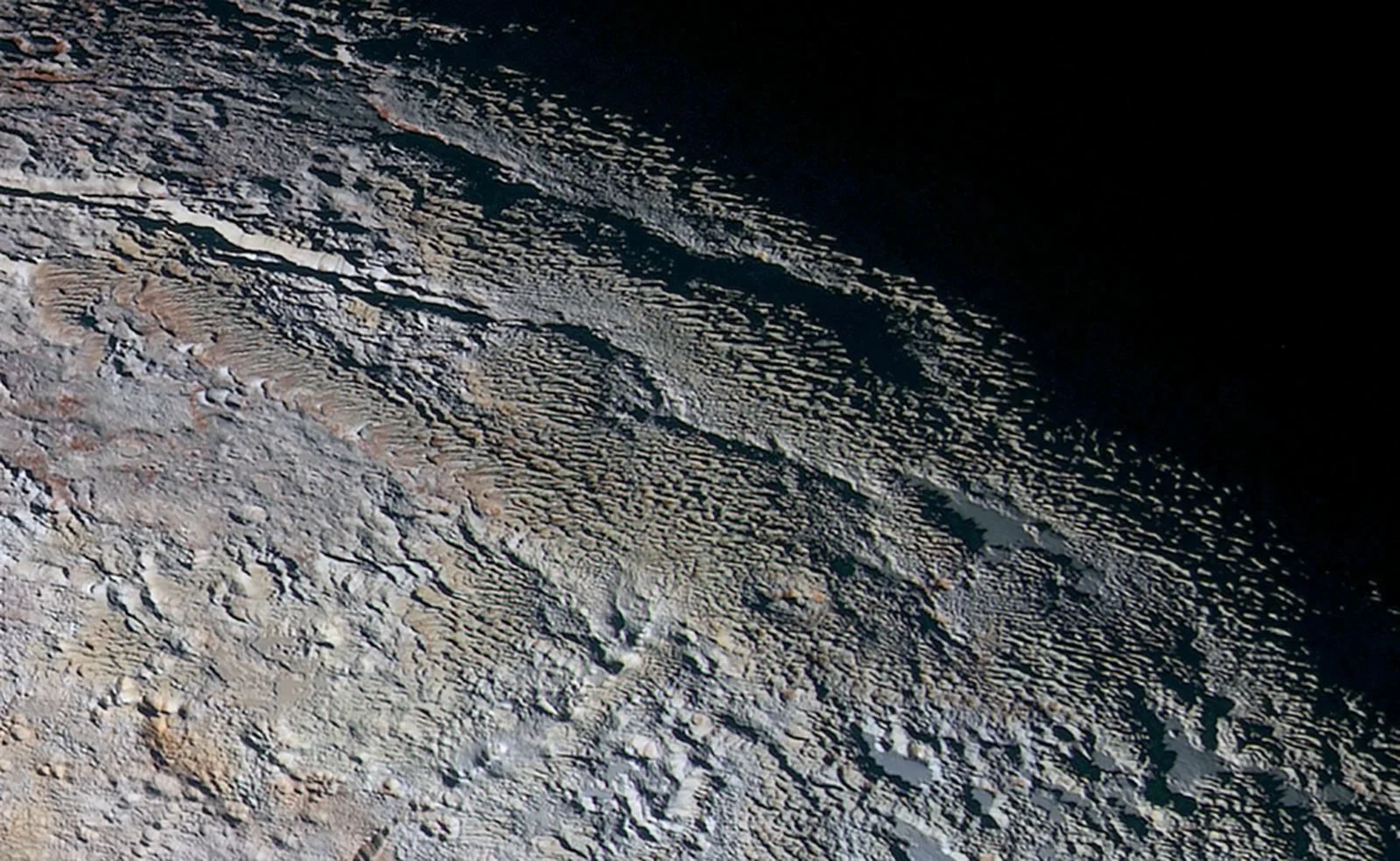

Far beyond the eastern side of Tombaugh Regio, we find Tartarus Dorsa, named after the dark, abyssal realm of torment in the ancient Greek underworld of Hades. Patterns of blue-grey ridges rise up along Pluto’s terminator line where day and night are separated. These ridges are estimated to be dozens of meters tall and hundreds of meters wide. Some geologists have noted these ridge patterns more resemble tree bark or snake scales than geological features. Astronomers are not really sure what is causing these bizarre features but hypotheses include tectonic forces or ice sublimation processes.

A paltry amount of reddish tholins pepper the terrain unevenly, a stark contrast to the deep red highlands of Belton Regio.

New Horizons also captured detailed images of Pluto’s moons. Once considered the solar system’s smallest planet and now classified as its largest dwarf planet, Pluto is accompanied by an unexpected five moons. This is surprising given that the far more massive terrestrial planets of the inner solar system have two moons or fewer. Most remarkable of all is Charon (pronounced “Kare-on”), Pluto’s largest moon, which is roughly half Pluto’s diameter (Pluto is 2,380 km). This makes it the largest moon in the solar system relative to the size of its parent body. Charon’s mass is enough that the barycenter of its orbit with Pluto lies in a space between. This has led some astronomers to believe both should be considered binary planets.

One striking feature revealed in New Horizon’s image of Charon is its reddish polar cap covered by the same tholins found across Pluto’s darker regions. This area was informally named Mordor Macula after the Lord of the Rings location. Astronomers speculate that this feature formed from the condensation of gases that escaped from Pluto’s atmosphere. Once they settled on Charon, they may have frozen and turned red by solar radiation. Appearing to cut through the center of Charon’s surface is a system of large canyons, some stretching over 1,000 km across. It’s been proposed that these canyons could be stress fractures from the swelling of a subsurface ocean. Also, interesting is how few craters mark the moon’s surface, suggesting the object is still geologically active.

Pluto’s other four moons are significantly smaller and irregularly shaped. Two were discovered the year before New Horizons launched while the other two were discovered by New Horizons itself on approach to the Plutonian system. The largest moon is Hydra at 55 km across while the smallest is Styx at a mere 7 km across. All four orbit in tight concentric circles around Pluto.

As New Horizons made its pass through the Plutonian system, it turned itself around to capture the dwarf planet eclipsing the nearly 5 billion km distant Sun. From this vantage, the Sun’s light passed through Pluto’s thin atmosphere at its periphery, creating a gorgeous blue ring. The color of the atmosphere makes sense considering both Pluto and Earth’s atmosphere are made primarily of nitrogen gas. Pluto is currently the only object beyond Neptune known to have an atmosphere.

After a nine-and-a-half year journey completed, New Horizons leaves Pluto and its moons behind. With its primary missions complete, it soared ever further into the cold reaches of the solar system. However, this would not be the last object the space probe would encounter.

Arrakoth flyby

January 1st, 2019

In the months leading up to its rendezvous with Pluto, the New Horizons team began searching for other Kuiper Belt objects that New Horizons would be able to study after. It was the Hubble Space Telescope that spotted several candidates but one was deemed most reachable. It was too distant for its shape and size to be determined at first. However, the object was predicted to pass directly in front of multiple background stars. This allowed astronomers to determine its shape by studying when its shadows were observed from different locations on Earth. As you can see, it has a bizarre peanut shape.

Originally dubbed Ultima Thule via a public contest, it was later renamed Arrakoth by the New Horizons team. This was granted on behalf of the Powhatan people, a Native-American tribe in Virginia and Maryland. The name comes from the Powhatan word meaning “sky.”

Four years beyond Pluto, at a distance of 6.6 billion km from Earth, New Horizons made its closest pass at a distance of just 3,500 km (about the width of Earth’s moon). Arrakoth is considered a contact binary, meaning it is actually two asteroids that collided and got stuck together. At its longest, Arrakoth spans 35 km across. The entire surface is tinted red, covered by tholins like those found on Pluto and Charon.

At the time, Arrakoth was the most distant object ever explored up close.

Where is it now? Where is it going?

January 19th, 2026

The New Horizons mission remains active to this day, taking distant snapshots of other Kuiper Belt objects. It has discovered about a hundred new ones and performed close flybys of about 20. The space probe was also used in conjunction with Earth (6.4 billion km apart) to demonstrate the most easily observable stellar parallax of the nearest stars, Proxima Centauri and Wolf 359.

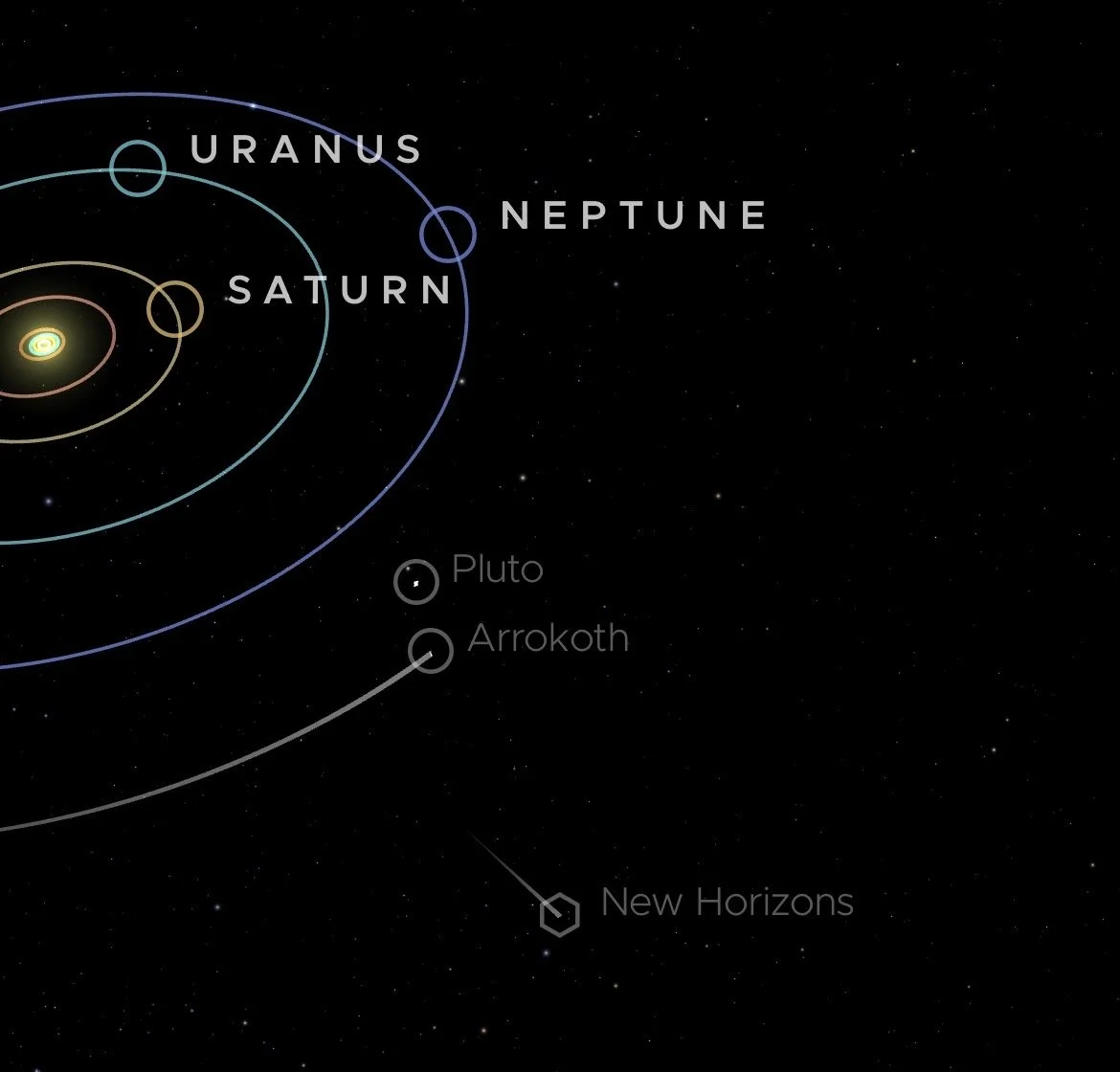

As of the publishing of this article, the New Horizons space probe is 9.6 billion km away (over 64 times further from the Sun than Earth), traveling through the Kuiper belt in the direction of Sagittarius. It takes nearly 9 hours for radio signals to travel each way. New Horizons is the fifth most-distant spacecraft from Earth. It is expected to exit the Kuiper Belt sometime between 2028 and 2029.

The vast majority of everything we know about Pluto is due to the New Horizons space probe and it continues to illuminate more and more about the furthest reaches of our solar system, too distant for Earth’s telescopes to discern. It was undoubtedly a proof of concept for the New Frontiers program and other missions would go on to bolster that track record, such as the Juno mission. As New Horizons coasts toward interstellar space, we hope it will continue to teach us all it can about the unexplored reaches of the solar system and what might lie beyond.