The Artemis II Mission

by Sam Atkins

After some delays, the March 6th launch of NASA’s Artemis II is finally approaching. This mission will send astronauts around the Moon for the first time in over half a century, paving the way for a future lunar landing. Let’s dive into how we got here, what Artemis II will look like, and what comes next!

Update: The launch of Artemis II has been delayed to March 6th and the article has been altered to reflect that.

What is the Artemis program?

The Artemis program is an ambitious initiative by NASA to return humans to the Moon. It will progress across numerous missions, each one building on the last, ultimately aiming to establish a sustained lunar presence and lay the groundwork for the first crewed mission to Mars.

Although the Apollo missions captured the imagination of the world, the last human set foot on the Moon in 1972, over 53 years ago. So why did we stop, and why are we going back now?

While NASA’s motivations were scientific and had planned for many more lunar landings, the funding of the Apollo program was primarily driven by political ends: competition with the Soviet Union. The United States’ endeavors into space were very expensive. NASA’s share of the federal budget during the Apollo missions was higher than it has ever been since. With the urgency to beat the Soviets gone and America beset by unpopular wars and economic strife, continued lunar missions began to feel costly and nonessential. NASA’s budget fell sharply from 5% in 1966 to just 1% in 1975. NASA shifted its focus to low-Earth orbit projects like the Space Shuttle program and robotic planetary missions such as the Voyager probes.

Over half a century later, NASA returns to the Moon, driven not by political rivalry and prestige, but by international cooperation, sustainability and science.

Modern technology now makes frequent, complex missions in space far more economically feasible and less risky than during the Apollo era. Rockets are more powerful, reliable and reusable. Materials science can create stronger, lighter spacecraft. Life support systems allow astronauts to remain in space longer and more safely. The advancement of robotics and computers allow for unprecedented levels of precision, problem solving and automation.

At the same time, space exploration is no longer dominated by the United States alone. Countries like China, India, Japan, Israel, South Korea and the United Arab Emirates have launched ambitious scientific missions into space. It’s also no longer the domain of governments. As space travel becomes cheaper and more efficient, private companies are playing an increasingly central role. SpaceX and Northrop Grumman transport supplies and innovate on space technology, Blue Origin and Virgin Galactic are pioneering space tourism, and Firefly Aerospace recently became the first private company to successfully land a spacecraft on the Moon. To avoid being left behind, America must lead the way.

Our evolving scientific understanding of the Moon has also changed the equation. One of the biggest discoveries is water ice found in permanently shadowed craters near the lunar poles. These resources could provide water, breathable oxygen, and even rocket fuel without needing to transport it from Earth. Nearby these reservoirs, at the rims of the craters are regions of near-constant sunlight, providing sustained solar power. All together, these regions could make a permanent presence on the Moon much more realistic and provide a good launch point for manned missions to Mars. Beyond this, the Moon’s rocky, cratered highland terrain offers new scientific challenges and opportunities far beyond the smooth lunar plains visited by Apollo astronauts.

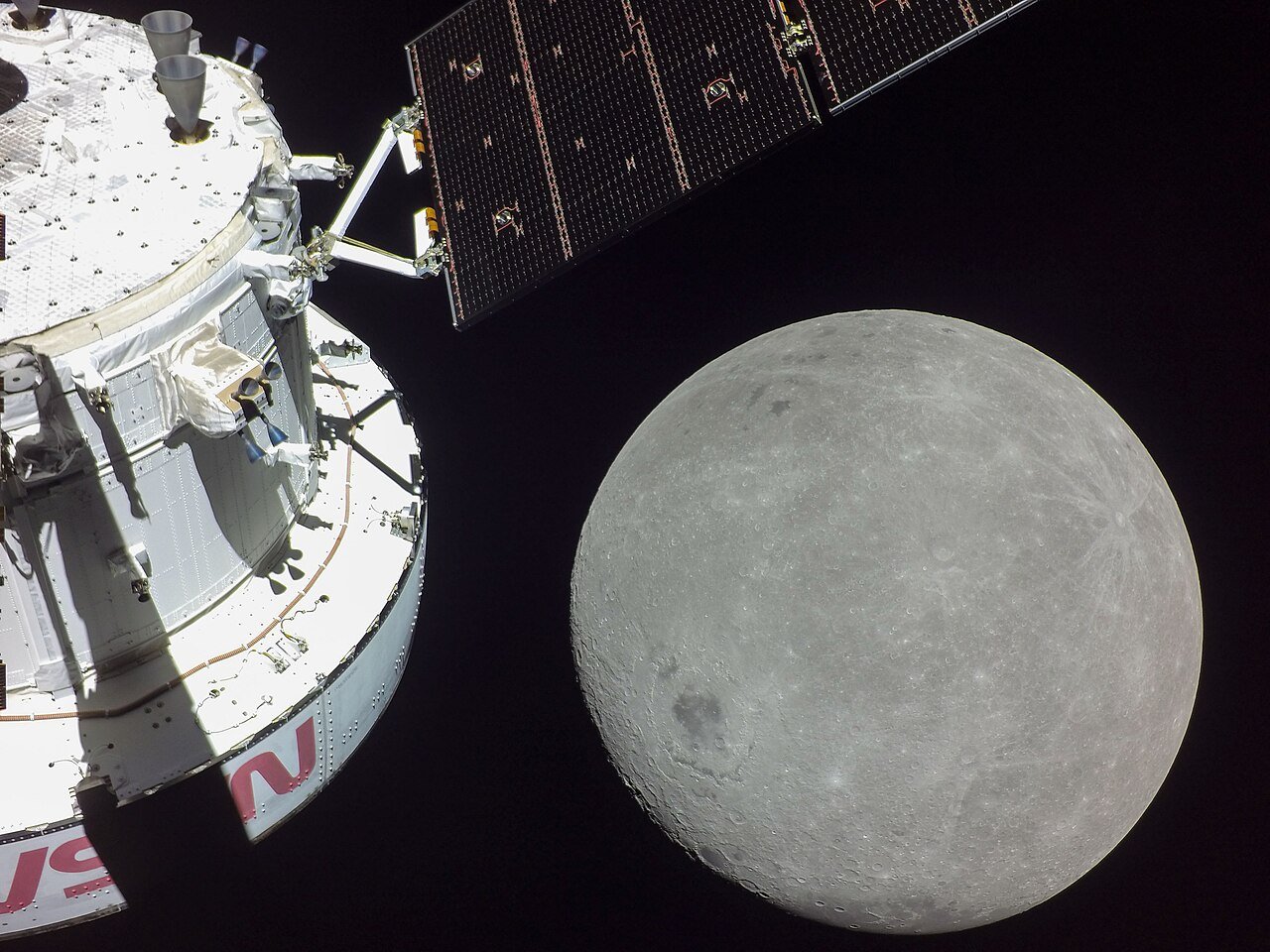

Artemis I

On November 16, 2022, NASA launched the inaugural mission of the lunar return program, Artemis I. Stacked atop the Space Launch System (SLS) rocket, the uncrewed Orion spacecraft was sent on a five-day journey to the Moon where it passed as close as 130 km above the lunar surface. Four days after passing the Moon, Orion entered into a crawling retrograde orbit 50,000 km beyond. After six days, Orion initiated a burn that would put it on a trajectory to perform a second flyby of the Moon and then head home. Upon its second pass, Orion came within 128 km of the lunar surface. On December 11th, 2022 (the 25th day of the Artemis I mission), the Orion spacecraft re-entered Earth’s atmosphere and splashed down safely into the Pacific Ocean.

This mission provided critical data that would support calculations and engineering for the next step, Artemis II. Originally slated for a September 2025 launch window, concerns with Orion’s life support systems and heat shield forced a delay. However, the new April 2026 launch window was later moved up to a March 6th, 2026, launch date! It seems that the technical issues were addressed and they are ready to go!

What is the objective of Artemis II?

Building upon the success of the Artemis I mission, Artemis II is a ten-day crewed lunar flyby mission. It will essentially be a faster, more direct version of the Artemis I journey, but this time with a four-astronaut crew on board. This is the second test-flight of the rocket and spacecraft to ensure they are capable and ready for a lunar landing. To be clear, this mission will not involve a lunar landing nor extravehicular activity. The focus of the mission will be on crew health, safety and system performance.

Meet the Crew and Spacecraft of the Artemis II Mission

REID WISEMAN 🇺🇸

Artemis II Commander

Hailing from Baltimore, Maryland, Reid Wiseman is an American naval aviator and engineer. He flew his first space mission aboard the International Space Station in 2014 as a flight engineer, where he spent six months conducting hundreds of scientific experiments and performing four spacewalks totaling over 27 hours. He later served as Chief of the Astronaut Office, acting as the principal advisor on astronaut training and operations. This extensive experience makes Wiseman a proven leader to command the Artemis II mission.

VICTOR GLOVER 🇺🇸

Artemis II Pilot

Victor Glover, a U.S. Navy captain from Pomona, California, is a self-described adrenaline junkie who once dreamed of becoming a stuntman, police officer, firefighter, or race car driver. He earned multiple engineering and systems degrees and has logged thousands of flight hours as a fighter pilot and test pilot. Glover piloted the first operational Crew Dragon mission to the International Space Station, where he completed a long duration stay, the first African American to do so. He is also slated to become the first black astronaut to fly around the Moon as the pilot of the Orion spacecraft during Artemis II.

CHRISTINA KOCH 🇺🇸

Artemis II Mission Specialist

An electrical engineer from Jacksonville, North Carolina, Christina Koch holds the record for the longest single spaceflight by a woman (328 days) and participated in the first all-female spacewalk. She has spent much of her career conducting research to develop space science instruments. Koch is no stranger to extreme environments, having worked for several years in the Arctic and Antarctic, facing isolation and harsh conditions. These experiences make her a natural choice as mission specialist for Artemis II, where she will become the first woman to fly to the Moon.

JEREMY HANSEN 🇨🇦

Artemis II Mission Specialist

From London, Ontario, Jeremy Hansen is Artemis II’s only Canadian astronaut. He graduated from the Royal Military College of Canada with a degree in physics, where he conducted research on wide-field satellite tracking. He later served as a CF-18 fighter pilot, leading tactical formations. Although Artemis II will be his first spaceflight, Hansen has extensive experience in spaceflight simulations and extreme analog environments, including deep caves (ESA CAVES) and undersea laboratories (NASA NEEMO). He will become the first Canadian to fly to the Moon.

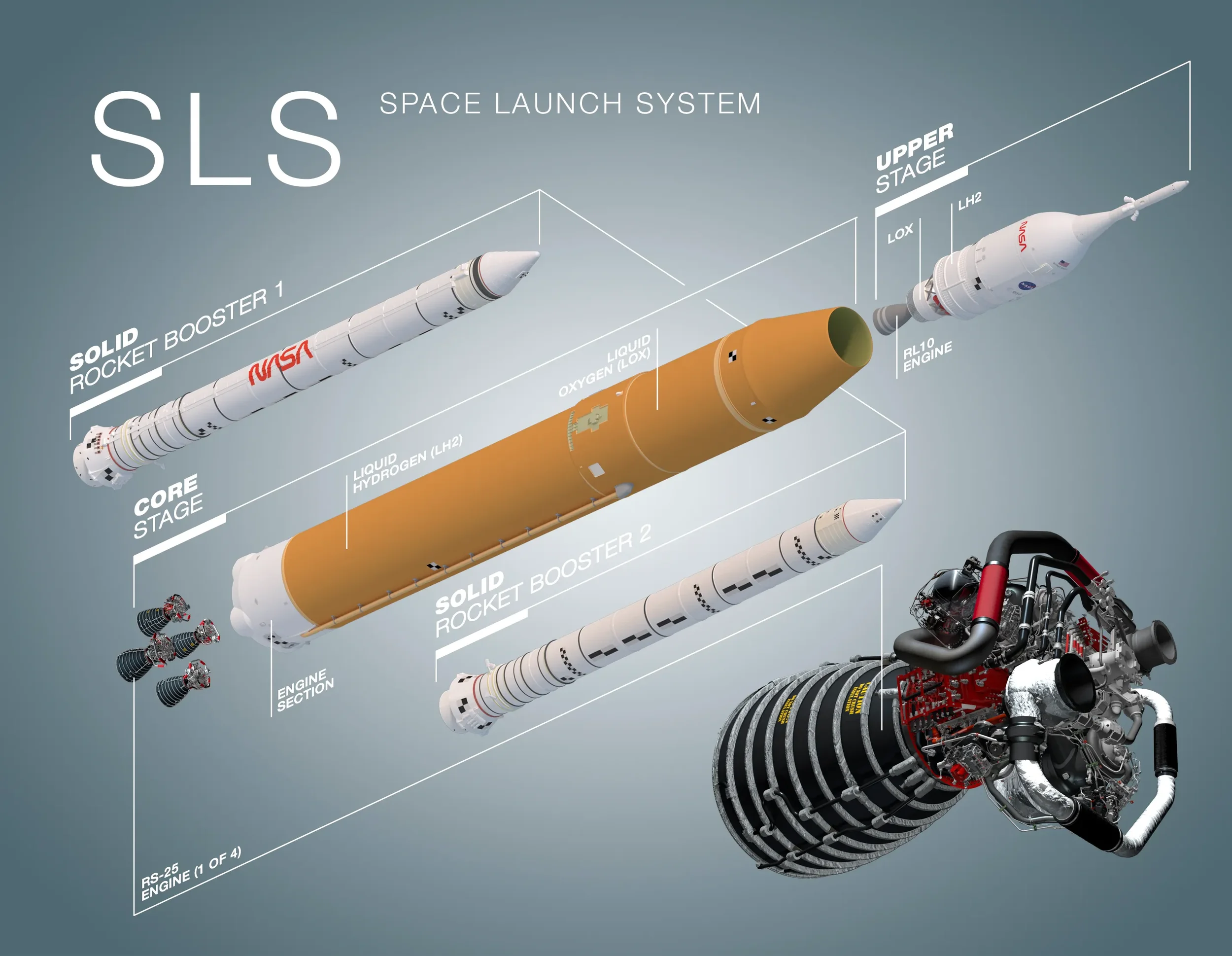

SPACE LAUNCH SYSTEM (SLS)

After the Space Shuttle’s retirement and the cancellation of the Ares rockets, NASA developed the Space Launch System (SLS) as its next super heavy-lift vehicle. SLS is the centerpiece of the Artemis program, designed to launch the crewed Orion spacecraft toward the Moon. It first flew during Artemis I, with Artemis II serving as its second test flight.

At the center of the rocket is the core stage (painted orange), which supports Orion and contains two cryogenic tanks: a smaller liquid oxygen tank above a much larger liquid hydrogen tank. These propellants feed four RS-25 engines at the base, upgraded versions of Space Shuttle engines. When ignited, the engines mix and burn the propellants at extremely hot temperatures, expelling exhaust at high pressure to generate lift.

To overcome the rocket’s enormous weight, gravity, and atmospheric drag at liftoff, SLS relies on two solid rocket boosters mounted on either side of the core stage (painted white). These boosters burn rapidly and provide immense thrust during the most demanding phase of launch. Together, the engines and boosters produce over 8.8 million pounds of thrust, making SLS the most powerful rocket NASA has ever built.

With Orion attached at the top, the whole vehicle stands 98 meters tall. Its height puts it as taller than the Statue of Liberty but shorter than the Saturn V rocket used by the Apollo missions.

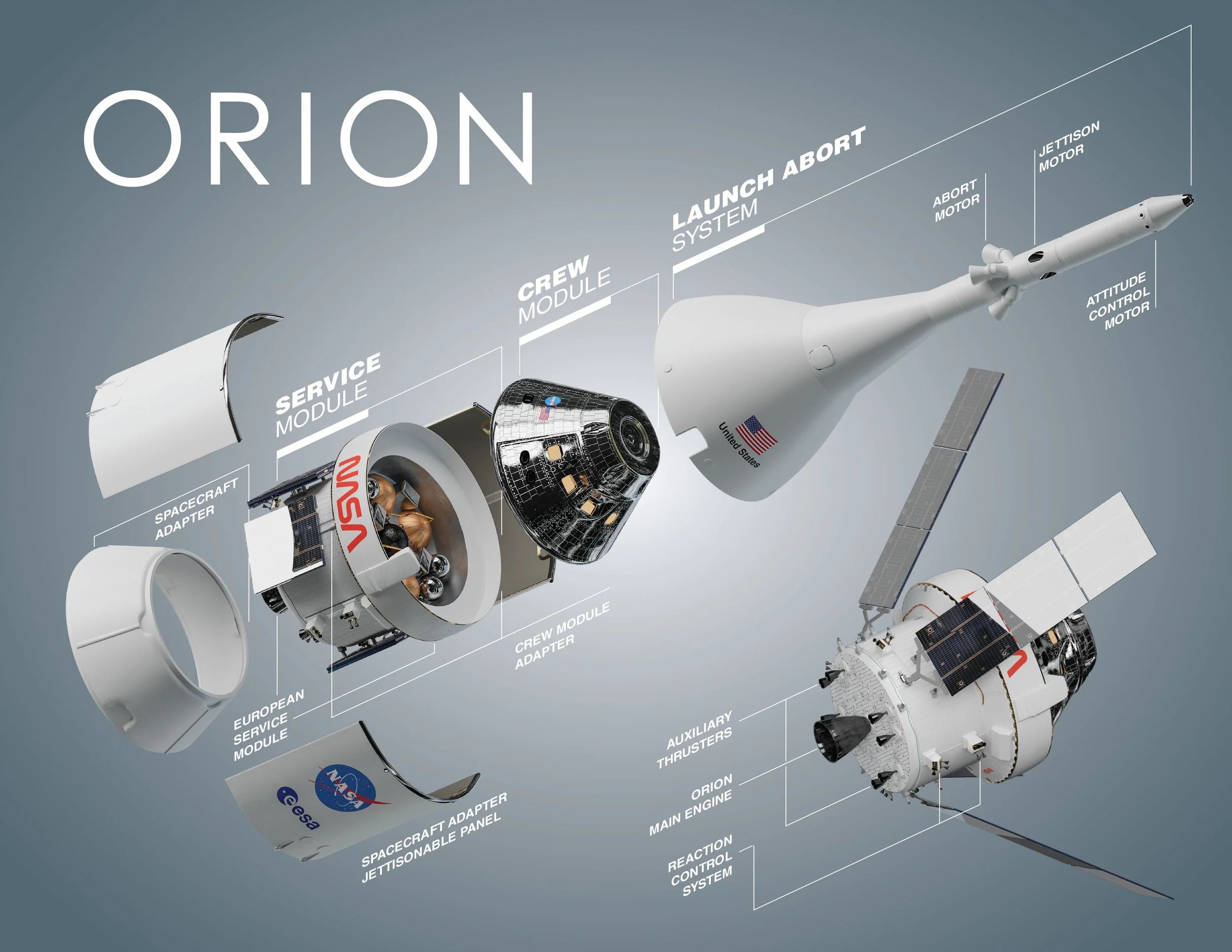

ORION SPACECRAFT

Mounted atop the core stage of the Space Launch System rocket is the Orion spacecraft. This is the multi-purpose crew vehicle that will carry the astronauts to the Moon and back. It is made of an aluminum-lithium alloy. The configuration of the Orion spacecraft is not that dissimilar to the Apollo spacecraft back in the day. At launch, Orion consists of three major components: the service module, the crew module and the launch abort system.

The Service Module, developed by Airbus and provided by the European Space Agency, is a cylindrical section at the base of the spacecraft that houses Orion’s power and propulsion systems. At the base is the single Orbital Maneuvering System Engine (OMS-E) which can provide 6,000 pounds of thrust. Flanking the sides are four deployable solar wings which provide electricity to the various systems (engine, life support, thermal control, etc.).

The Crew Module, developed by Lockheed Martin, is the cone-shaped pressurized capsule mounted atop the service module. It is occupied by the four Artemis II crew members, one more than the Apollo command module. Underneath the capsule is a curved heat shield that will protect the crew from superheated air as they re-enter the Earth’s atmosphere. It is the only part of the Artemis II vehicle that will remain by the mission’s end.

The Launch Abort System (LAS) is a missile-shaped tower mounted to the front (top) of the spacecraft, covering the crew module. In the event of an emergency during launch or ascent, say the rocket is about to explode, the LAS will propel the Orion spacecraft away from the SLS rocket and land it safely in the ocean. Should everything go smoothly, the LAS will be discarded along with the core stage of the SLS.

With all three components attached, the Orion spacecraft stands just over 20 meters tall and 5 meters wide, making up about a fifth of the SLS rocket’s total height.

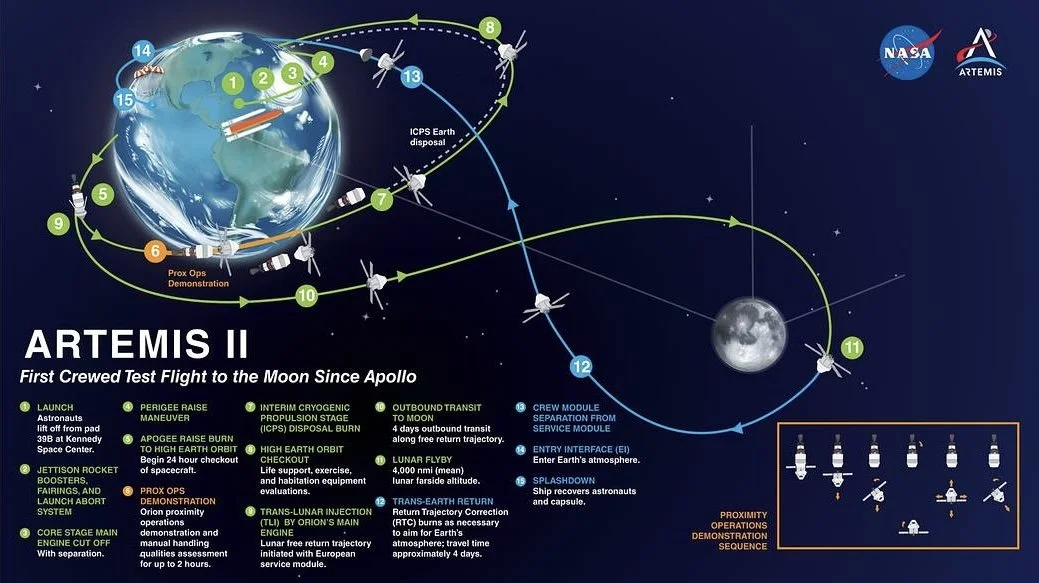

Artemis II mission overview

It should be reemphasized that Artemis II is not a lunar landing mission, it is a lunar flyby mission. Taking place over ten days, the Artemis crew will leave Earth, fly around the Moon and then return. This will be the first time humans have travelled beyond low-Earth orbit since the Apollo 17 mission and will take the crew further from Earth than any human has ever been.

Artemis II will most resemble the 1968 Apollo 8 mission, except it won’t be entering into a lunar orbit.

Launch

March 6th, 2026

Artemis II begins at the Kennedy Space Center in Cape Canaveral, Florida. At 11:20 p.m. EST, the Space Launch System will ignite its four main engines along with its solid rocket boosters. The rocket will lift off from Launch Complex 39B and climb into the night sky. About two minutes into flight, the SLS will jettison the solid rocket boosters at an altitude of about 50 km and a speed of 5,000 km/h. Once the SLS is above the densest part of the atmosphere, the Launch Abort System will be jettisoned. Eight minutes into the flight, the SLS will have reached an orbital velocity of 28,000 km/h. At this point, the core stage of the rocket will shut down and most of it will be jettisoned. However, a small upper section of the core stage called the Interim Cryogenic Propulsion Stage (ICPS) will remain attached.

Earth orbit

March 6th, 2026

Video credit: NASA’s Eyes on the Solar System

After reaching space, the remaining ICPS will use its single rocket engine to place Orion into an elliptical orbit around Earth, ranging from just 185 km at perigee (the closest point above the planet) to 2,200 km at apogee (the farthest point). Orion will complete this first loop around Earth in a little over 90 minutes. Once that orbit is complete, the ICPS will ignite again, pushing Orion into a far more stretched version of the orbit (shown above). This second orbit will stretch from a perigee of 380 km to an apogee of 70,000 km (more than five Earth diameters away). With its role complete, the ICPS will separate from the Orion spacecraft, which will then drift slowly along this vast orbit for roughly 24 hours.

The purpose of this extended, highly elliptical orbit is to allow for the Artemis crew to switch Orion to manual control and demonstrate the spacecraft’s maneuverability. Commander Wiseman and Pilot Glover will use onboard cameras and window views to pilot Orion toward and away from the separated ICPS, evaluating the spacecraft’s handling, hardware, and software. The test will provide critical in-flight data and operational experience that cannot be replicated on the ground, helping prepare crews for rendezvous, proximity operations, docking, and undocking in lunar orbit in future missions like Artemis III.

Note: Upon separating the ICPS, a cache of CubeSats stored between it and the Orion spacecraft will be released. These are shoe box-sized satellites that will enter into high Earth orbit to collect measurements on the effects of the space environment on electrical components.

Translunar injection

March 7th, 2026

Video credit: NASA’s Eyes on the Solar System

Once Orion reaches perigee a second time, it will initiate an engine burn from its service module to propel it towards the Moon. This burn is known as translunar injection (TLI) which will accelerate the spacecraft onto a free-return trajectory (shown above). This means the speed and direction will allow Orion to swing around the Moon and back to Earth without the need for additional burns. After reaching a top speed of about 38,000 km/h, Orion’s path will primarily follow the gravitational influences of the Earth and Moon, though small course corrections may be made. It will take the Orion spacecraft about four days to travel from Earth to the Moon.

During the four days, the crew will monitor spacecraft systems, gather data on the effects of deep space travel, and perform trajectory correction burns as needed.

Lunar flyby

March 11th, 2026

Video credit: NASA’s Eyes on the Solar System

On the fifth day of the Artemis II mission, humanity will make its first crewed flyby of the Moon in over 53 years.

Calculated into its translunar injection burn, Orion’s free-return trajectory is designed to pass the Moon in such a way that lunar gravity sends the spacecraft around the far side and back toward Earth, all without expending any additional fuel (shown above). Imagine you are running past a friend and, at just the right moment, they grab your arm. You do not stop. Instead, you swing around them in a wide arc, and when they let go, you are flung back in the direction you came from. Orion does the same thing with the Moon. The Moon’s gravity briefly grabs the spacecraft, bends its path around the Moon, and redirects it back toward Earth.

As Orion flies behind the Moon, the crew will lose contact with Earth for about 45 minutes. During this expected communications blackout, the astronauts will photograph and observe the Moon’s far side. This will put them into an extremely exclusive group, becoming four of only 28 humans to ever see the Moon’s far side with their own eyes. One of the most striking differences between the far side and the near side, is the lack of maria. These are the dark-gray regions that form the “Man in the Moon” pattern. They are ancient lava plains, created when volcanoes spilled molten basalt across the lunar surface, which cooled into smooth, flat plains. The far side, in contrast, is much more heavily cratered, with very few maria.

The Orion spacecraft will reach its closest pass of the far side of the Moon at a distance of about 6,500 km (almost two moon widths). From here, the Moon will appear 30° across, about 120 times its typical size from Earth. At this point, the crew could break the distance record set by the Apollo 13 mission for the farthest humans have traveled from Earth. This is also when they will reach their fastest speed during the flyby, about 8,000 km/h. However, the acceleration to this speed will be so gradual that the crew will not feel any increase in G-forces.

After the Earth comes back into view, the lunar gravity will slingshot Orion back towards home. This will mark the beginning of another four-day coast through space. NASA anticipates performing further trajectory correction burns during the return flight to ensure accurate Earth re-entry.

Re-entry & splashdown

March 15th, 2026

On the tenth and final day of its lunar mission, Orion will approach Earth. It will re-enter the planet’s atmosphere at a steep angle of roughly 6-7° and at an unprecedented speed of about 40,000 km/h, the fastest ever attempted by a crewed spacecraft. Because Orion is returning from lunar orbit rather than low Earth orbit, it carries far more kinetic energy, making a precise entry angle crucial. If the entry is too steep, the crew could experience extreme heating and dangerously high G-forces. If the entry is too shallow, Orion could skip off the atmosphere like a stone on water.

Well, actually, Orion will kind of do the latter using a technique called a skip re-entry. After jettisoning the service module, the crew module will dip into the atmosphere and use its lift to bounce back outward, dissipating much of its kinetic energy. It will then re-enter again for the final descent. This maneuver allows for a more precise landing near the coast of San Diego, California. This technique dates back to the Apollo mission but their navigation and computing technology was not sufficient enough for the precision needed. Artemis II will be the first human-crewed mission to attempt this maneuver with modern guidance systems.

The cone-shaped crew module is equipped with small thrusters that allow it to fine-tune its approach angle. It will enter the atmosphere heat shield first, slamming into and tearing through the air at tens of thousands of kilometers per hour. Extreme pressure and friction will superheat the surrounding air, making the crew module appear as a fiery meteor. The heat shield will reach temperatures exceeding 2,700°C, burning away its ablative material in a controlled manner and preventing the crew module from being incinerated. The same force that generates heat will also slow the spacecraft rapidly. The Artemis crew, lying on their backs and facing away from the direction of travel, will experience the highest G-forces of the mission, around 8-9 g, pressing them firmly into their seats.

Once Orion slows sufficiently, it will deploy a cluster of large parachutes to reduce its descent speed to less than 30 kilometers per hour. After splashdown into the Pacific Ocean, inflation devices will keep the crew module afloat. The U.S. Navy will recover the crew and spacecraft from the waters using a San Antonio-class amphibious transport dock.

What comes next?

Artemis II serves as a second test of Orion’s capabilities and life support systems, as well as the operational effectiveness of safety protocols, trajectory calculations, and lunar observation. After this mission, NASA will begin preparations for the next step in the Artemis program. Naturally, Artemis II will be followed by Artemis III. This is the big one.

Planned for a broad 2028 launch window, Artemis III aims not just to land humans on the Moon for the first time since 1972, but specifically near the lunar south pole, where discoveries about water ice could pave the way for sustainable exploration and future missions to Mars. No crew has been announced yet, but based on past practice, it will likely be different from the Artemis II crew. As more details emerge and the launch date approaches, I will provide a deeper dive into Artemis III.