Chelyabinsk: Chaos Over Russia (Again)

by Sam Atkins

Russia is no stranger to the dangers posed by space. The largest meteor fall in recorded history occurred just over a century ago, when an asteroid detonated above the remote wilderness of Siberia near the Tunguska River. Had it occurred over a densely populated area, the destruction would have been catastrophic. That hypothetical scenario was all but realized in 2013 when a large meteor exploded high above the city of Chelyabinsk. Unlike Tunguska which was witnessed by only a few hundred rural settlers, the Chelyabinsk event was seen by millions and captured on video.

Note: Tap or hover over images for captions and credits.

It was an early winter morning on February 15, 2013. As the Sun rose, the citizens of Chelyabinsk navigated the icy streets on their commute to work. The city is home to over a million people, making it the seventh largest city in Russia. Despite economic struggles since the Soviet Union’s collapse in 1991, Chelyabinsk remains one of the largest industrial centers around the Ural region. At around 9:20am, a blinding light tore across the dim, pearlescent sky. When the flash receded, it left behind a long cloudy trail that seemed to split the sky open.

Many citizens were driving when the blaze occurred:

“I was driving in the car across the square. Suddenly the square lit up with a bright, bright light, not a normal light. There was literally three or four seconds of bright light, then back to normal. As I could see from the car, this trail appeared. Then when I was driving, the explosion went off.”

Vasily Rozhko, resident of Chelyabinsk recalling his experience behind the wheel

“I was driving to work, it was quite dark, but it suddenly became as bright as if it was day. I felt like I was blinded by headlights.”

Viktor Prokofiev, resident of Yekaterinburg (just north of Chelyabinsk)

Others witnessed the flash from indoors:

“When I saw some white narrow cloud moving outside the window, I ran up to it and saw a huge blinding flash. It was like the way I would imagine a nuclear bomb.”

Nadezhda Golovko, deputy head of a Chelyabinsk school, describing the initial fireball sighting just before the shock wave.

“After the flash, nothing happened for about three minutes. Then we rushed outdoors… the door was made of glass, a shock wave made it hit us.”

Yekaterina Melikhova, high school student

Since 2008, Russia and parts of Eastern Europe saw an explosion in dash cam usage, years before the technology became mainstream elsewhere. This surge was largely a response to widespread accident and insurance fraud. By the early 2010s, a significant portion of private vehicles recorded continuously on loop. As a result, many urban centers in Russia effectively became sprawling sensor arrays.

This means that not only was the Chelyabinsk meteor witnessed by millions, but it was also recorded on video.

Among the numerous recordings, Aleksandr Ivanov’s video became the most widely circulated and recognizable footage of the Chelyabinsk meteor. This was apparently recorded from a smaller city about 140 km north of Chelyabinsk, called Kamensk-Uralsky. Little is known about Ivanov, and he doesn’t appear to have given any interviews following the incident, but his footage more than speaks for itself:

Video credit: Aleksandr Ivanov

Following the blinding flash, any witnesses described a prolonged quiet, lasting minutes, almost as if the meteor had simply disappeared into nothingness. Countless people in their homes, schools and workplaces were drawn to windows to investigate the illumination coming from outside, only to see nothing. The power of this meteor was questioned, then subsequently answered. As onlookers stood bewildered, the eerie silence was shattered by a series of ground-shaking booms. Windows exploded in people’s faces and building roofs caved in. Within a 30 km radius, roughly 100,000 buildings were damaged, and within 50 km, about 1,500 people were injured.

We will get into the aftermath soon, but this terrifying incident naturally raised a lot of questions. Was there no awareness of the meteor ahead of time? Why did it seem to vanish in midair? If it was just a single meteor, why did so many booms follow? Why did the sounds arrive so long after the flash?

The Approach

Because the meteor’s approach was seen and recorded from so many vantage points, this made it relatively easy for astronomers to calculate and trace its trajectory from Earth’s atmosphere back to its original orbit around the Sun.

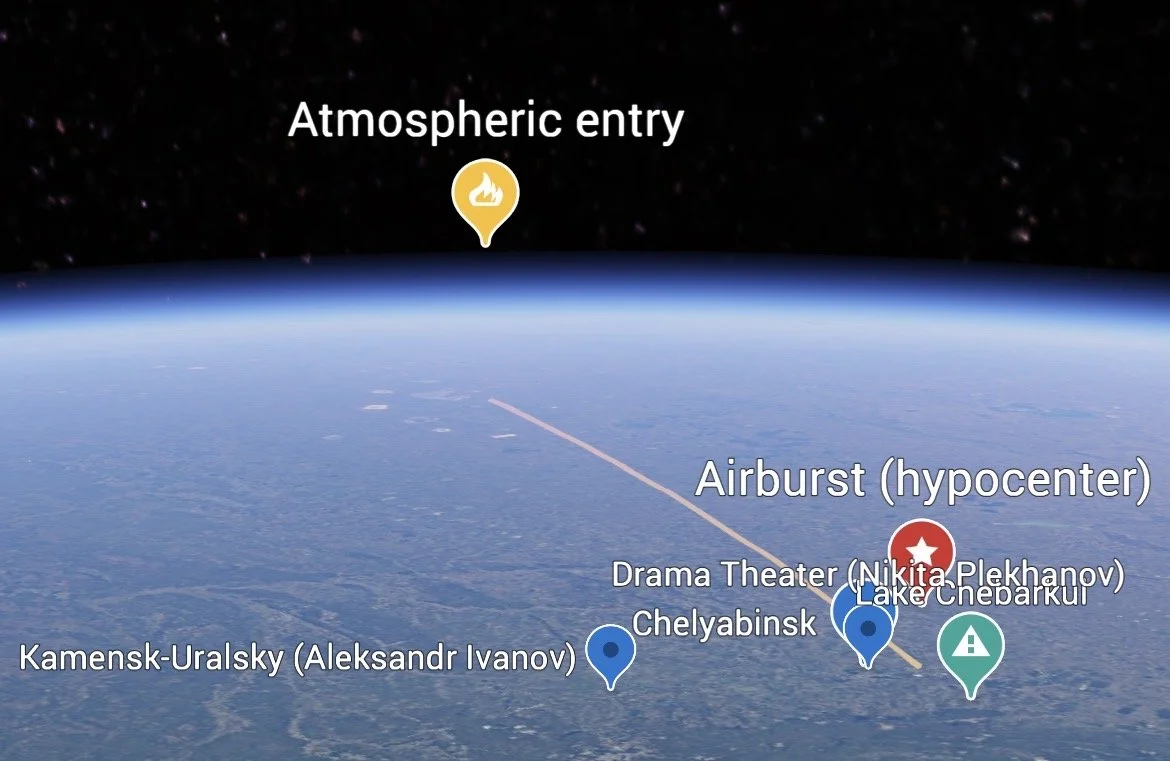

The meteor entered Earth’s atmosphere over the neighboring country of Kazakhstan, moving 19 km/s (70,000 km/h) from southeast to northwest at a shallow angle of about 15-20°. Considering it was still early morning, this means the asteroid approached from near the direction of the rising Sun. This explains why there wasn’t any warning as the Sun’s glare would have masked the asteroid’s approach. Video evidence allowed astronomers to compare the meteor’s angular position across the screen against buildings and the horizon. The movement of the meteor was also corroborated with the movement of shadows which are shown prevalently in stationary security footage.

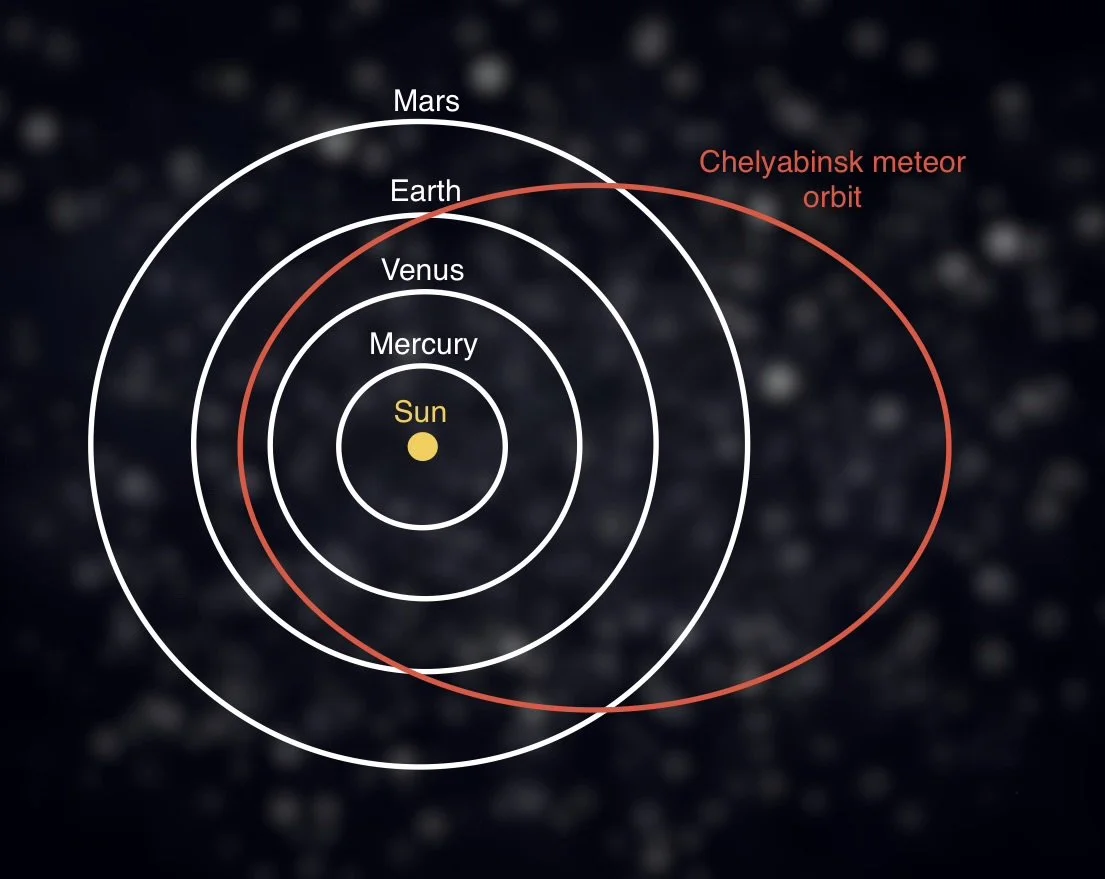

Altogether, astronomers triangulated the speed and angle of entry to determine the asteroid’s orbit was correlated with those of Apollo-type asteroids. These are near-Earth asteroids (NEAs) which spend most of their time beyond Earth’s orbit but regularly cross inside of it. Think of a stretched oval that slightly overlaps with Earth’s nearly circular orbit. Apollo asteroids are the largest group of NEAs by number. These types often originate in the asteroid belt until gravitational tugs from either Jupiter or Mars shook them loose into more interior orbits. Entering into an orbital resonance with Jupiter, the asteroid’s orbit becomes more and more eccentric until its perihelion crosses into Earth’s orbit. However, there is some evidence that the Chelyabinsk asteroid may have been set on its collision course with Earth by a collision with another asteroid. More on that later.

The Airburst

Countless rocks and pebbles drift through the solar system, and some cross Earth’s path. They tear through the atmosphere at such extreme speed that the pressure and friction superheat them, causing them to glow as meteors. What happens next depends mostly on their size. Tiny particles burn up almost instantly, creating brief streaks of light known as shooting stars. This happens millions of times every day, and can be seen pretty regularly in dark, remote regions. At the other extreme, massive asteroids can survive the heat and collide with the surface in a devastating explosion. Most famously, the Chicxulub meteor collided with the surface 66 million years ago, wiping out the dinosaurs. Between these extremes are meteors that break apart midair in what is called an airburst. This is what happened with the Tunguska meteor a century prior and also what happened in Chelyabinsk.

As the meteor enters Earth’s atmosphere, around 100 km above the surface, it begins to glow white hot as it rips through the air at 19 km/h. The closer it gets to the surface, the atmosphere gets thicker, the heat intensifies and the meteor burns brighter.

At 40 km above the surface, atmospheric density increases dramatically, causing the meteor’s brightness to spike beyond that of the Sun. This makes the meteor visible from 100 km away. This is the start of the airburst. At 30 km above the southern Ural region, the meteor’s structural integrity fails. No longer able to withstand the extreme compression of the thick air slamming into it, the meteor fragments and bursts outwards.

What was once a single compact body is now a scorching debris cloud of thousands of fragments. Despite this, the combined surface area blooms, still affecting the surrounding air as if it were one expanding body. This generates incredible atmospheric drag to slow down the meteor’s remains, and the glow dissipates. Much more consequential is the transfer of momentum to the surrounding air, compressing it violently and pushing it outward. This creates a powerful shockwave with the power of 500 kilotons of TNT, or more than 30 Hiroshima bombs going off at once.

As the brightness faded, it left behind a long trail of water vapor, dust and an uncanny quiet.

From any single vantage point, it’s difficult to judge how far away a meteor truly is when it’s set against a vast, empty sky. People often assume it’s nearby because it appears extraordinarily bright and moves so quickly. Confusion sets in by the initial silence of the airburst, unaware that the powerful shockwave is on its way. Then, the delay tricks them into thinking the distance will soften the explosion.

In this case, the airburst occurred roughly 30 kilometers above the surface, meaning the closest possible observer would have been directly beneath it. Sound travels at about 343 meters per second, so the shockwave took nearly a minute and a half just to reach the ground directly below the blast (hypocenter). 25 km out from that point, the shockwave took almost two minutes. 50 km out, it took almost three minutes. 100 km out, it took over five minutes.

Countless witnesses recalled an echoing series of startling booms like “thunder, but sharper and louder.” Some described it as like an “army cannon firing repeatedly.” The first of these booms was ear-piercingly loud and shook the city to its foundations, setting off car alarms everywhere. This was the actual shockwave caused by the airburst. The subsequent booms were residual shockwave echoes and the thuds of remaining meteor fragments pelting the ground from kilometers away.

For those indoors, it was more dangerous. The walls trembled. Doors slammed shut. Then, there were those curiously studying the left behind dust trail from their windows, unaware of the vulnerable position they’d put themselves in. When the shockwave hit, windows shattered inward. Anyone standing at them was blasted with shards of glass moving at automotive speeds.

Upon fracturing, the meteor fragments continued on at a reduced speed, no longer glowing from friction. They ranged from small pebbles to rocks hundreds of kilograms in weight.

The Aftermath

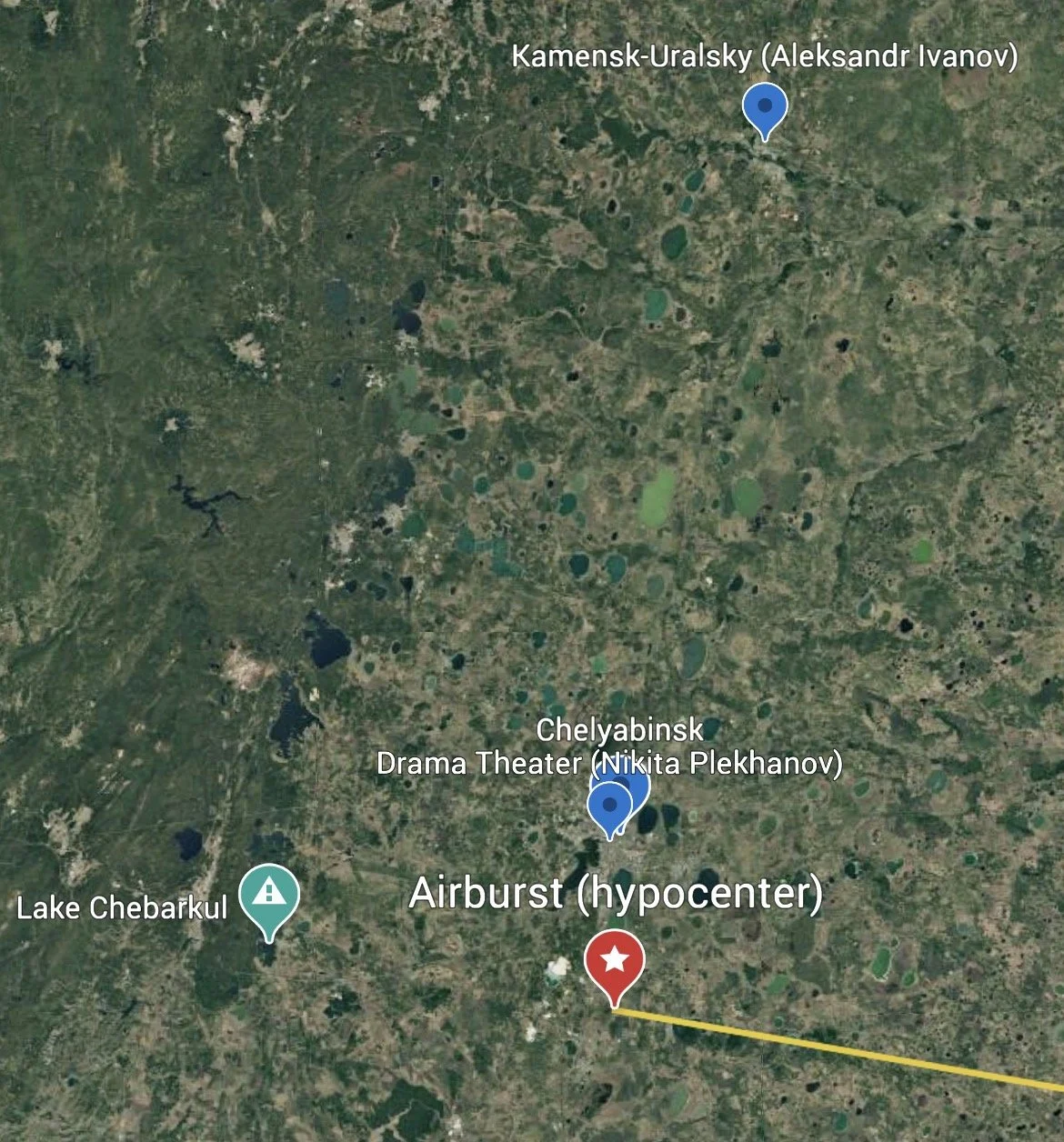

The Chelyabinsk meteor released an estimated 500 kilotons of energy in its airburst, which was largely directional. The explosion occurred south of Chelyabinsk as the meteor moved westward toward Lake Chebarkhul, concentrating the most intense overpressure and debris in the region between these points. The shockwave also radiated sideways, which actually made the meteor more destructive than if it had made it to the surface. Its energy was distributed over a wider area, affecting the entire city of Chelyabinsk. That being said, the shockwave was slower and less compressed beyond the main blast corridor.

The damage to property was primarily concentrated in Chelyabinsk and some surrounding towns. At least 7,000 buildings sustained structural damage, including cracked walls and ceilings and blown-in doors. Older or poorly reinforced structures, such as Soviet-era brick or panel buildings, as well as factories and warehouses with large surface areas, suffered damage to roofs and walls. About 100,000 buildings had their windows cracked or outright shattered by the shockwave overpressure, especially if they were within 50 km of the airburst.

Miraculously, there were zero known fatalities resulting from the Chelyabinsk meteor. However, nearly 1,500 people were injured. This was mostly caused by lacerations from broken glass as people peered out their windows. The vast majority of this was minor cuts but over a hundred people were hospitalized with at least two in serious condition.

There was a notable instance in which a quick-thinking fourth-grade teacher named Yulia Karbysheva anticipated the impending blast wave. She ordered her 44 students away from the windows and hide under their desks, saving them from harm. However, she could not protect herself when glass shards severed a tendon in her left arm and sliced into her left hip. She was hospitalized immediately with serious injuries that required surgery. Fortunately, doctors assured that she would recover without disability. Karbysheva has been hailed a hero for her calm leadership and selflessness.

Some hundreds of people also reported temporary retinal burns and vision impairment from staring at the extremely luminous flash of the airburst, brighter than the morning Sun. None of the eye damage is known to have been permanent.

Over the following weeks, thousands of meteor fragments were recovered from lakes, snow and soil. The field of debris where meteor fragments were found stretched about 100 km long and 10 km wide. The largest chunk was recovered by divers at Lake Chebarkul about 70 km east of the airburst. Weighing about 650 kilograms, the meteor fragment had punched a large 7-meter hole into the lake’s frozen surface and sank to the bottom. This impact was actually captured in the background of security camera footage of a lakeside residence. These fragments would give us the biggest insights about the meteor itself.

The Meteor

Much was learned about the meteor itself after the chaos has settled.

Unlike meteors of the past, this happened in a highly populated urban center with the benefits of 21st century technology. Dash cam and security footage, and even satellites captured the meteor’s entry into the atmosphere, allowing scientists to calculate the meteor’s trajectory and speed. Seismographs measured vibrations caused by the shockwave hitting the surface. Fragments of the meteor itself were recovered in great number, giving scientists the opportunity to study its geology.

Based on the speed of the meteor and energy released by the airburst, the asteroid was determined to be about 20 meters in diameter and weighing at least 10,000 metric tons. This is about the wingspan of a Boeing 747. Had it been comparable to the 50-meter-wide Tunguska meteor, we wouldn’t be talking about broken windows and cuts. We would have been talking about leveled buildings and hundreds of thousands of deaths.

Laboratory analysis identified it as an LL chondrite asteroid, containing small spherical grains of silicate minerals with a low amount of iron. The meteorite has veins of black material which had experienced high-pressure shock and were once partly melted. This suggests that the Chelyabinsk meteor was likely broken off from a larger asteroid during a collision in the main asteroid belt. This may have even been the event that initially put the asteroid on its fateful crossroads with Earth.

If we learn anything from the Chelyabinsk meteor, it’s that the solar system is a huge shooting gallery, and we aren’t capable of seeing everything. We must respect that our place here on Earth is more tenuous than we think. That is why we must take capitalize on our modern technology and techniques to protect ourselves. Large telescopes, both on the ground and in space, allow us to track the movements of thousands of asteroids and provide ample warning. Space missions are testing new ways of deflecting or destroying potential threats. If we don’t prepare now, we could join the dinosaurs in the dirt.