Tunguska: A Phantom From The Skies

by Sam Atkins

NOTE: Tap or hover over images for captions and credits.

Echoes of Destruction

On June 30th, 1908, seismometers across Eurasia registered intense tremors, some readings spiking as high as 5.0 on the Richter scale. They came without warning and didn’t resemble typical seismic activity. Despite pouring over data and reports, nobody knew where the source originated. Something shook the Earth and seemed to have left no trace. For the next few days, people in these regions reported an eerie, pearlescent glow hanging in the night sky. Some claimed they could read the newspaper outdoors at midnight with only the aid of the strange shimmer above. Even American astronomers at the Mount Wilson Observatory (California) and the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory (Massachusetts) observed a sudden and dramatic drop in atmospheric transparency, along with a noticeable dimming of sunlight. It lasted for weeks to months. Investigations revealed an unusual concentration of fine dust particles suspended in the upper atmosphere.

Stories slowly emerged from the remote wilderness of Siberia. Locals spoke of a beam of bluish light splitting the sky, a blinding flash, an earth-shaking explosion that boomed like artillery shells and laid the land low. Some even claimed it to be the destructive fury of some kind of god. Most of these accounts were carried by traders, missionaries and scattered newspaper reports. They were largely dismissed as exaggerations and folklore, the wild imaginations of isolated nomads. Still, there were some who saw through the doubt and sensed something very real and terrifying transpired. What could have caused such a massive release of energy, in a place with no volcanoes, no known fault lines, and no signs of human warfare?

Something happened in Tunguska, and it was not of this world.

A Not-So-Expedient Expedition

While only a small number of rural residents saw what happened firsthand, the Tunguska event went unexamined by the rest of the world for years.

The Siberian taiga was one of the most remote places on Earth, largely untouched by human presence. Thick boreal forests and perilous swamps stretched to every horizon, ready to consume inexperienced travelers. In winter, the land was a dark, frozen graveyard. In summer, the land became a mosquito-ridden bog. With no detailed maps available, travelers would have to rely on indigenous guides to find their way. This was the edge of the world and few dared to make the trek.

While the Siberian wilderness beckoned only the bravest to enter, the political instability in Russia ensured that no proper expedition would be organized anytime soon. The autocratic regime of Tsar Nicholas II was under constant threat from revolutionaries while his expansionist efforts in the Far East suffered humiliating military defeat. The situation deteriorated further when the country was thrust into World War I, sending millions of Russian conscripts westward to fight in Europe. It all came to a head in 1917, when a wave of uprisings and civil war culminated in the overthrow of the Romanov dynasty by the Marxist Bolsheviks.

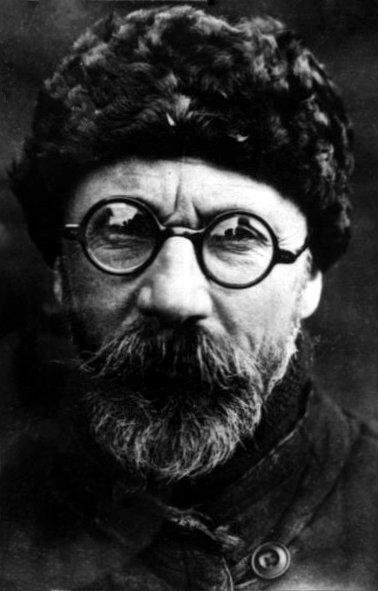

Thirteen years passed and knowledge of the Tunguska incident remained fragmented, ultimately fading into legend. A mineralogist named Leonid A. Kulik was working at the Mineralogical Museum in Petrograd (renamed from St. Petersburg during WWI to sound less German). He was in charge of cataloging the meteorite falls in Russia for the Soviet Academy of Sciences. The new Bolshevik government, motivated by a need to drive industrialization and economic development, chartered a geological survey of the Siberian region in 1921 to assess the land’s mineral resources, particularly iron ores and coal. While preparing for the expedition, Kulik stumbled upon a strange news report dating back to 1908. Witnesses spoke of a powerful explosion in central Siberia without explanation or investigation. As he scoured for more information, he became convinced that a meteorite had impacted the Earth somewhere in the Siberian wilderness.

Kulik left Petrograd traveling east by train across over 4,000 km (2,500 mi) of the Trans-Siberian Railway. This vital infrastructure had been battered and worn down by four years of civil war. Even in 1921 and even out in Siberia, the Bolsheviks were still putting down armed uprisings from a variety of groups. The railway had been maintained just enough to keep Russian civilization in motion. Kulik would spend at least two to three weeks sitting in train cars crowded with Red Army soldiers, refugees and cargo. As the vast, wounded countryside passed by, hour after hour, it felt like he was leaving one jungle and entering another.

He finally arrived in Krasnoyarsk, the largest settlement in Central Siberia. While a modest city hosting just tens of thousands of people, it was also a central hub for commerce in the region as well as a key military objective during years of civil war. Despite food shortages and social unrest, this city would serve as the anchor in the region for Kulik to do his work. The bulk of his official efforts were devoted to surveying the geology of the region on behalf of the Soviet Academy of Sciences. He mapped the terrain, documented erosion patterns, cataloged mineral deposits, and gathering samples for further study back in Petrograd. Even as he fulfilled his assigned tasks, his thoughts often drifted toward the tales of a powerful but mysterious explosion in the Siberian taiga thirteen years earlier.

Tales from the Taiga

Local news reports out of Central Siberia collected by Leonid Kulik provided him with his initial window into what transpired on that summer morning in 1908. While carrying out his official duties, Leonid Kulik himself interviewed scores of witnesses across the Yenisei Governorate to recall that morning.

Note: Russia did not adopt the Gregorian calendar, which is used by most of the world today, until a decade after the Tunguska incident. As a result, accounts and reports from 1908 date the event on the 17th of June instead of the 30th.

One such example is an early report from the Sabir newspaper just a few days after. On the morning of June 17th, 1908, villagers near Karelinski (north of Kirensk) witnessed a bright, bluish-white cylindrical object in the sky that descended for about 10 minutes. As it approached the ground, it blurred into a cloud of black smoke, followed by loud sounds like falling stones or artillery. The ground shook, windows rattled, and flames were seen emerging from the cloud. The event caused widespread panic among villagers, who feared the world was ending. A witness in the forest nearby also heard repeated explosive sounds over 15-minute intervals.

Other witnesses from around the region over the next month shared similar stories. Villagers in Kezhemskoye reported hearing a loud wind-like noise, followed by a powerful thump and an earthquake that shook buildings. This was followed by a series of loud thumps, an underground rumbling like multiple trains, and five to six minutes of repeated booming noises like artillery fire. A faint, ashen cloud was later seen in the north, gradually fading by mid-afternoon. Strong ground tremors and a pair of loud explosions like cannon fire were heard by witnesses in the village of Lovat, just east of Kansk. A report from Siberian Life newspaper even explicitly identified the source of it as a meteorite.

By 1921, these accounts were 13 years old and mostly relied on memory alone. Kulik knew he had to be cautious of hearsay. However, the consistency of the testimonies, from the timing, direction and nature of the light and sound, was compelling. Kulik was convinced that a meteorite had impacted the Siberian wilderness, but eyewitness accounts can only take a narrative of this kind so far. Finding the crater was what he really needed and the stories he’d heard all pointed north.

The Podkamennaya Tunguska River basin was a remote region to the north of Krasnoyarsk. Far from any roads or rescue, the Siberian taiga was dense and unyielding, a vast expanse of coniferous forest rising between ancient stone outcrops and winding, silvery waterways. To venture north was to issue a bold challenge to the ancient wilderness itself.

While he had become a scientist working in the big city, lecturing in classrooms and conducting research in libraries and labs, Kulik was no stranger to surviving in harsh conditions. Not long before his academic career, he served in the Russo-Japanese War and fought in the brutal trenches of World War I. He’d long endured the cold, the hunger, the mud and the danger. However, even the most hardened and battle-tested soldiers were no match for what Siberia had in store. The expedition was not organized for such an intense journey. Provisions and gear were inadequate and the maps drawn of these barely charted lands were unreliable. What’s worse, the waning winter had given way to the spring thaw. The frozen forests had turned into flooded bogs and mosquito ponds. With supplies running dangerously low, the region was simply inaccessible and Kulik had to make the difficult decision to turn back.

Kulik would bring his 233 meteorite samples and witness testimonies and return to Petrograd. He was not giving up, though. He was getting ready. Kulik would begin to compile all of the evidence he’d collected around the region and make his case to the Soviet Academy of Sciences for a serious, properly-funded and equipped expedition.

The 1927 Expedition

Six years passed. The Bolsheviks had consolidated power in the now formally established Soviet Union. Rebuilding infrastructure and industry was still a top priority. This boded well for Kulik’s ambitions which had not faltered. Since his return from Siberia, he’d spent years writing reports and lobbying government officials. He argued that the mysterious reports of explosions coming out of the Tunguska wilderness was likely caused by a massive meteorite. If such an object could be located, there was a potential treasure trove of raw materials in the form of meteoric iron that they could harness.

In 1927, Kulik secured state backing to return to Siberia for a full-scale scientific expedition to find the source of the fabled Tunguska explosion.

Leonid Kulik departed Leningrad (renamed again from Petrograd) ahead of the spring melt, hoping to find drier ground by the time he began trekking through the taiga once more. This time, however, he wasn’t going alone. Kulik was accompanied by a small party consisting of a topographer who would help map the blast zone, a photographer who would document the journey and devastation, and some field assistants who would help navigate the Siberian wilderness. Supplies were basic: tents, axes, rations, rifles for hunting and protection and, of course, scientific instruments.

Again, Kulik crossed the vast countryside via the Trans-Siberian Railway. It was a smoother and more peaceful journey in a post-civil war Russia.

Once they reached the Yenisei Governorate, they would regularly transition between horse-drawn sleds to cross harsh terrain and boats that were specially crafted for the expedition’s frigid, turbulent rivers. Makeshift charcoal pits would serve to cook the meat and fish they would hunt.

From Kezhemsk, they travelled overland to Vanavara, a remote but bustling fur trading post. This would be the last semi-permanent settlement before they reached the area Kulik expected to find the impact site. While they made their preparations for the last leg of their journey, Kulik took the opportunity to interview the locals as this area would have undoubtedly experienced some of the most intense effects of the blast.

One of the most famous and commonly cited eyewitness accounts came from a local Russian farmer that Leonid Kulik interviewed at Vanavara, named S.B. Semyonov: “I sat on the steps of my house facing north. Suddenly the sky in the north split apart, and there appeared a fire that spread over the whole northern part of the firmament. At this moment I felt intense heat, as if my shirt had caught fire. I wished to tear my shirt off and throw it away, but at this moment a powerful blast threw me down from the steps. I fainted, but my wife ran from the house and helped me up. After that we heard a very loud knocking, as if stones were falling from the sky."

Some of the closest witnesses were local reindeer herders of the Evenki, a group of people indigenous to the region. They seemed hesitant to even speak of that day. Some believed that the explosion was the wrathful curse of Ogdy, the god of thunder. Kulik also heard of an indirect account recorded the year prior by a researcher named I.M. Suslov. Two Evenki brothers named Chuchan and Chekaren were sleeping in their riverside hut when a sudden wind and loud whistle woke them. One was thrown into the fire as the ground shook and trees crashed outside. A massive explosion, the first of five, knocked over their hut. Trapped under debris, they saw burning trees and a blinding flash like a second sun, followed by thunder. After escaping, they witnessed more flashes and thunderclaps, each weaker than the last, under a clear morning sky.

By April, the snow had melted, and they entered into the forest on horseback. Just south of the site, the Evenki guides they had hired became spooked and refused to continue on. Kulik had to return to the nearby village, and his party was delayed for several days while they sought new guides. They eventually struck a deal with some Evenki hunters led by a man named Ilya Potapovich. With the party suffering from infection and malnutrition, they made their final trek north. On April 13th, 1927, they came over a ridge and saw something unsettling. Something… unbelievable.

Ground Zero

Millions of scorched trees were toppled outward in eerie radial precision and stripped of their branches. Potapovich said, “This is where the thunder and lightning fell down.” Seeing this land frozen in time two decades after the destruction, it was understandable why the locals reached for supernatural explanations. Kulik said, “It is as if a giant hand swept the forest flat. All is dead - silent, yet not peaceful.” The devastation was widespread, stretching as far as the eye could see. Kulik would later write in his diary, “One has an uncanny feeling when one sees 20 to 30-inch giant trees snapped across like twigs, and their tops hurled many yards away.”

They began exploring the blast zone by walking the perimeter and putting together a topographical map, noting the direction of the bent trees. It seemed as if the blast zone was not a perfect circle but some kind of butterfly shape. The team cut cross-sections from standing and fallen trees to study growth rings. They noted an abrupt drop in growth around 1908, providing strong evidence that something catastrophic had occurred that year.

Numerous bogs found around the area were predicted by Kulik to be craters from meteorite debris. They attempt to pump the water out of one of them and excavate the ground, hoping to find a piece of the impact. No meteorites. All they found was a rotting tree stump which ruled out Kulik’s crater idea.

The most bizarre feature of the blast zone was at the epicenter. The crater that Leonid Kulik had sought for many years and many more kilometers to find, wasn’t there. Instead, amidst a swamp where the asteroid should have slammed into the Earth, they found a standing forest of charred, branchless trees. Kulik noted in his journal, “the solid ground heaved outward from the spot in giant waves, like waves in water.”

With only three to four days’ worth of food left, they were forced to conclude the second expedition. Kulik would return to the site a few years later in 1929 to do more thorough ground excavations but still turned up empty handed. You can only imagine the utter frustration he must have felt after so much time and hardship.

In 1938, Kulik made his third and final return to Tunguska, this time taking to the skies. Charting a reconnaissance plane to fly over the blast zone, Kulik took over 1,500 aerial photographs to document the characteristic butterfly-shaped pattern of the felled trees, indicating that the meteor had come in from the southeast. This provided the first large-scale visual record of the event’s aftermath which would be crucial to future investigations by other scientists.

Unfortunately, history tends to repeat itself and further inquiries would have to be again put on hold due the political upheavals of the 20th century. In June 1941, Nazi Germany set its sights east and invaded Russia. Ever the patriot, Leonid Kulik volunteered to go the frontlines as part of a paramilitary militia and defend his homeland. The next year, he was captured by enemy forces and later died of typhus in a German prisoner of war camp.

What Actually Happened?

The absence of a crater or meteoric debris puzzled Kulik and other scientists. The mysterious blast and flattened forest sparked a parade of wild theories over the following decades. One proposed that a tiny black hole pierced the Earth, entering over Siberia and exiting in the North Atlantic. Another claimed extraterrestrials detonated a nuclear device or self-destructed their ship. A persistent legend still circulating online blames Nikola Tesla. At the time, Tesla was experimenting with wireless power at his Wardenclyffe Tower in New York. According to the theory, he had converted the technology into a directed energy weapon and, during a test aimed at the Arctic, he accidentally overshot and struck Siberia instead. These explanations, while imaginative, are unsupported and contradicted by overwhelming evidence.

Other explanations for the Tunguska explosion were more grounded in science, rather than science fiction. Soviet scientists suggested the explosion could have been a violent eruption of natural gas or methane from a highly-pressurized pocket deep underground.

The most commonly accepted theory is that a meteor entered Earth’s atmosphere and exploded before ever hitting the ground. This is known as a meteor airburst. The meteor, which is estimated to be 65 meters in diameter, would have been moving at incredible speed, colliding with the atmosphere at great force. This superheated the air around the meteor, causing it to glow blindingly bright. The meteor was not strong enough to withstand the ablation and exploded several kilometers above the Siberian surface with the force of a 15-megaton bomb. The resulting shockwave would have been powerful enough to flatten 2,000 square kilometers of forest (roughly the size of London). The meteor broke apart into several smaller pieces that barraged the ground like a massive incendiary shotgun blast. The successive loud thumping would have been the individual pieces of debris slamming into the ground.

A lot of this lines up. Even Kulik himself had proposed some version of this, and later his colleague and successor E.L. Krinov as well. But if the meteor simply exploded into many pieces, shouldn’t he have found them all over the blast zone? In 2013, a team led by Victor Kvasnytsya from the National Academy of Sciences in Ukraine inspected samples taken from the Tunguska impact site in 1978. The samples, from a layer dating to 1908, were found to contain traces of lonsdaleite, a diamond-like mineral formed under extreme conditions, such as a meteorite collision. In other words, the meteor rocks were there, but they were just really small. Too small for Kulik to have recognized them.

At least three people are unofficially believed to have died as a result of the airburst, possibly the only known instance of human fatalities caused by a meteor. As tragic as those deaths were, it was remarkably fortunate that the meteoroid exploded over such a remote area. Had it arrived a few hours later and detonated above a densely populated city, the resulting death toll and devastation would have been historic.

Even more than a century later, visible traces of the Tunguska explosion still scar the Siberian wilderness. While most of the millions of fallen trees have since rotted away, remnants of the radial pattern remain in both fallen and scorched trees. The regrowth pattern of trees in the blast zone is very peculiar. The surviving trees showed accelerated growth, likely fueled by the increased nutrients provided by the dead trees. At ground zero, the haunting section known as the shattered forest remains. The trees, positioned just below the explosion, were stripped of their branches and scorched but remained upright like blackened telephone poles.

Scientists have learned much about this event, from its cosmic origins to the scale of destruction to the enduring impact on the environment. However, many answers continue to elude us and Tunguska remains one of the most mysterious events in human history. While we see the resilience of our planet to recover from the most cataclysmic wounds, the terrifying power of this explosion is a reminder that our place here on this Earth is not promised.

The danger of asteroids has been ever-present throughout Earth’s history but recent advances in technology have made defending against these cosmic collisions a real possibility. One of the most serious steps forward has been NASA’s 2022 DART mission and the ESA’s currently in-progress Hera mission. Read more about them here: ESA’s Hera Mission (Updated) — Harford County Astronomical Society, Inc.

Another fascinating story of an asteroid colliding with Earth is the one and only Chicxulub asteroid which wiped out the dinosaurs 66 million years ago. To experience the violent end of the Mesozoic Era and the science behind it, read here: Chicxulub: The End of the Age of Reptiles — Harford County Astronomical Society, Inc.