Milankovitch Cycles

by Sam Atkins

You may sometimes hear people reference climate cycles that Earth seems to go through periodically across thousands of years. While these are sometimes falsely cited as the cause of modern climate change, these cycles are a very real thing that bring Earth from ice age to ice age. How do we know these cycles exist? What causes them? How do we know they aren’t responsible for modern climate change? Let’s dig deeper!

NOTE: Tap or hover over images for captions and credits.

The history of Earth is written directly into its own depths. In places like the Grand Canyon, layers of rock sediment build up over millions of years, with each new stratum stacking on top of the last. This preserves a natural timeline in which geologists can study and figure out how Earth has changed over the ages.

We see very similar signatures of the past embedded in Earth’s polar ice caps. Drilling deep into Arctic and Antarctic ice sheets, scientists can extract long cylinders of material called ice cores. Just like in rock strata, these ice cores act like geological calendars, with the newer ice forming above older ice. The treasure buried within these cylinders comes in the form of trapped dust and air bubbles. These microcosms of ancient climates are extracted and analyzed for their greenhouse gases, isotopic ratios and as well as the size, shape and composition of dust. When combined, scientists can estimate how hot the Earth was, how often it precipitated and how much volcanic activity there was, among other things.

Across decades of careful observation, scientists have compared how these layers reveal the ebb and flow of Earth’s climate. A very interesting pattern emerged that shows longer periods where Earth gets colder, dustier and drier, with advanced glaciation (aka ice ages) followed by brief periods where Earth gets warmer, the glaciers recede, sea levels rise and forests reemerge (interglacial periods). In more recent geological history, glacial periods have lasted 80,000-90,000 years while interglacial periods have lasted only 10,000-20,000 years. Earth is currently in the middle of an interglacial period.

In the latter half of the 19th century, scientists like and James Croll and Milutin Milankovitch began to posit a connection between these cycles of glacial and interglacial periods and the ever-changing orientation of the Earth to the Sun.

While we often simplify the Earth as a tilted sphere that moves in a circle around the Sun, the truth is more nuanced, and those nuances matter over longer and longer time periods. Earth’s movement around the Sun are not static. It changes gradually. There are three main ways in which the geometry of Earth’s motions around the Sun changes and we call them Milankovitch cycles:

The eccentricity of its orbit

The obliquity of its axial tilt

The precession of its axial tilt

The Eccentricity Cycle

Earth orbits around the Sun, not in a perfect circle, but in an ellipse. This is an oval shape in which the Sun lies, not at the center, but at one of two focal points. This means that as the Earth orbits around the Sun, there are points at which Earth is closer, with the closest point being known as perihelion, and points at which Earth is further, with the furthest point being known as aphelion. Between perihelion and aphelion, which are located opposite each other, Earth’s distance from the Sun changes by about 5 million km.

There are two things that happen between these two points as a result of the change in distance:

At perihelion, Earth receives more sunlight. At aphelion, Earth receives less.

At perihelion, Earth moves faster. At aphelion, Earth moves slower. This is a consequence of Kepler’s laws of planetary motion. This is also the reason why seasons are different lengths. Currently, because summer and spring are closer to aphelion, they last slightly longer than winter and fall.

Note: Many people mistake the elliptical nature of Earth’s orbit to be the cause of the seasons through each year, which are primarily driven by its axial tilt.

Some elliptical orbits are more stretched out than others, causing a greater range of distances between the orbiting body and the parent body. For example, the orbits of comets are often incredibly eccentric, where their perihelion can be closer to the Sun than Mercury while their aphelion can reach way out beyond Neptune. The degree to which an object’s orbit is stretched out is known as its eccentricity.

To make matters more complicated, scientists now understand that the eccentricity of Earth’s orbit changes over time due to gravitational tugs from other planets, known as perturbations, mainly Jupiter and Venus. As you can see in the graphic above, this means the distance between perihelion and aphelion is elastic, stretching and contracting like a rubber band. These variations occur in a well-studied pattern known as the eccentricity cycle that occurs in shorter (and more prominent) 100,000-year cycles within longer (and more subtle) 400,000-year cycles.

The eccentricity of Earth’s orbit oscillates between being nearly circular (eccentricity ≈ 0.005) and mildly elliptical (eccentricity ≈ 0.06). Although these values may sound small, they’re actually the difference between Earth receiving 7% more sunlight at perihelion than at aphelion versus receiving 23% more. The effects of the former on Earth’s climate are negligible, but the effects of the latter can be profound over time. Also, as eccentricity decreases, the length of the seasons evens out.

The Earth is currently in the process of becoming less eccentric and is approaching its least eccentric.

The Obliquity Cycle

Earth’s rotational axis is the imaginary line around which the planet spins, creating the day/night cycle. This axis is not perfectly upright relative to the planet’s orbital plane. Instead, it is tilted at an angle of 23.5°. As said earlier, this axial tilt is what accounts for Earth’s seasons throughout the year. When the northern hemisphere is tilted towards the Sun, we get summer. This is because the sun rays are reaching the surface at a more direct angle and the hemisphere gets warmer. When the northern hemisphere is tilted away from the Sun, we get winter. This is because the sun rays are reaching the surface at a more oblique angle, spreading the energy across a larger area, and the hemisphere gets colder. In between, we get the transitional seasons of spring and fall.

Note: Whenever the northern hemisphere experiences one season, the southern hemisphere experiences the opposite season (summer and winter, spring and fall).

What many people might not know is that the Earth’s axial tilt is also not fixed, just like the eccentricity of Earth’s elliptical orbit. While it is currently tilted towards the orbital plane at an angle of 23.5°, it oscillates from 22° to 24.5° (about a 2.5° change) and back again over a 40,000-year period. As you might imagine, the greater the tilt, the more extreme the seasons and the lesser the tilt, the milder the seasons.

Earth’s axial tilt is currently in the process of recession, causing the planet to become more upright.

The Precession Cycle

For generations, people living in the northern hemisphere have been able to look up in the sky each night and find Polaris positioned steadfast in the same place. This is because Earth’s north pole is coincidentally pointed directly at it. It has made Polaris a critical marker for navigators on land and sea to determine the northern direction. This is why it is nicknamed the North Star.

Note: In reality, the north pole doesn’t point toward Polaris exactly and the star does move around the celestial north pole in tiny little circles, but it’s too small to notice with the naked eye across a whole night. Good enough!

What you might not know is that this was not always the case and won’t always be the case.

Day to day, we see Earth’s axial tilt as fixed, always pointing toward the Sun during summer and pointing away from the Sun during winter. We learned earlier that the 23.5° angle of this axial tile is not fixed. It’s also the case that the direction that this axial tilt points towards is also not fixed. Instead, it actually sways around in a circle like the wobble of a spinning top. This is called precession.

It takes about 26,000 years for Earth’s axial tilt to trace out a full circle. During this time, there have been other stars that were considered the North Star. Back in 3,000 B.C., it was Thuban in the Draco constellation that was the pole star. Then, from 1500 B.C. to 500 A.D., it was Kochab in Ursa Minor. Since then, Polaris became pole star and remains so to this day. Because it happened to be the pole star when humans discovered the concept, it has been immortalized in its name which means “belonging to the pole.” However, that won’t always be the case. In 10000 A.D., it will be Deneb in the Cygnus constellation, and in 14000 A.D., it will be Vega in the Lyra constellation. It won’t be until 28,000 A.D. that the celestial north pole will come all the way back around to Polaris.

This is also why the equinoxes, the two points where the ecliptic crosses the celestial equator, have changed between the different zodiac constellations over time. Today, the spring equinox (March) is located in the zodiac constellation Pisces, but in 4500 B.C., it was in Taurus and later in Aries. By 2600 A.D., it will be in Aquarius. The autumnal equinox (September) currently resides in the zodiac constellation Virgo, but in 4500 B.C., it was in Scorpius and later in Libra. By 2600 A.D., it will be in Ophiuchus.

Why does this precession happen?

Due to the centrifugal force of its rotation, Earth is not a perfect sphere. It is ever so slightly wider at the equator than it is pole-to-pole by about 43 km. You can consider the Earth’s extra width as kind of like a bulge of mass. Just like the rest of Earth, these bulges are pulled on by the gravity from every other object in the solar system, but especially the Sun and Moon (remember perturbations).

Due to Earth’s axial tilt, the half of the bulge closest to the Sun is off-center to either the north or south while the furthest side of the bulge is tilted in the opposite direction. This creates a small amount of torque (a twisting action) as the Sun pulls harder on the near side. This torque is perpendicular to the axis of Earth’s rotation and causes the Earth’s axis to wobble. The same thing happens with the Moon as well. The magnitude of the torque from the Sun or Moon varies with the angle between the Earth's axis and the direction of the gravitational attraction.

If the Earth were a perfect sphere, there wouldn’t be any precession.

The implication of all this, in terms of Milankovitch cycles, is that the solstices and equinoxes change over time relative to when Earth reaches perihelion and aphelion in its orbit. Right now, Earth reaches perihelion in its early northern winter and aphelion during its early northern summer. 13,000 years from now, it will be reversed. Combining summer with perihelion will result in a hotter summer season while combining winter with aphelion will result in a colder winter. More extremes!

So, we have three Milankovitch cycles which change the distribution of solar energy across latitudes and across seasons. Because they work independently of each other, we can expect to experience different combinations of extremity over time. Their combined and cumulative effects create the long-term changes in Earth’s climate and take us between glacial and interglacial periods.

To trigger an ice age, these three must converge to minimize summer solar radiation in the Northern Hemisphere, since that’s where most of the world’s ice sheets are. This allows ice sheets to grow and an ice age to begin. Once an ice age has begun, certain feedback mechanisms amplify the cooling effect, such as the high albedo of icy surfaces which better reflect away sunlight or a reduction in atmospheric carbon dioxide which traps heat. Speaking of which…

An Explanation For Climate Change? Not So Fast…

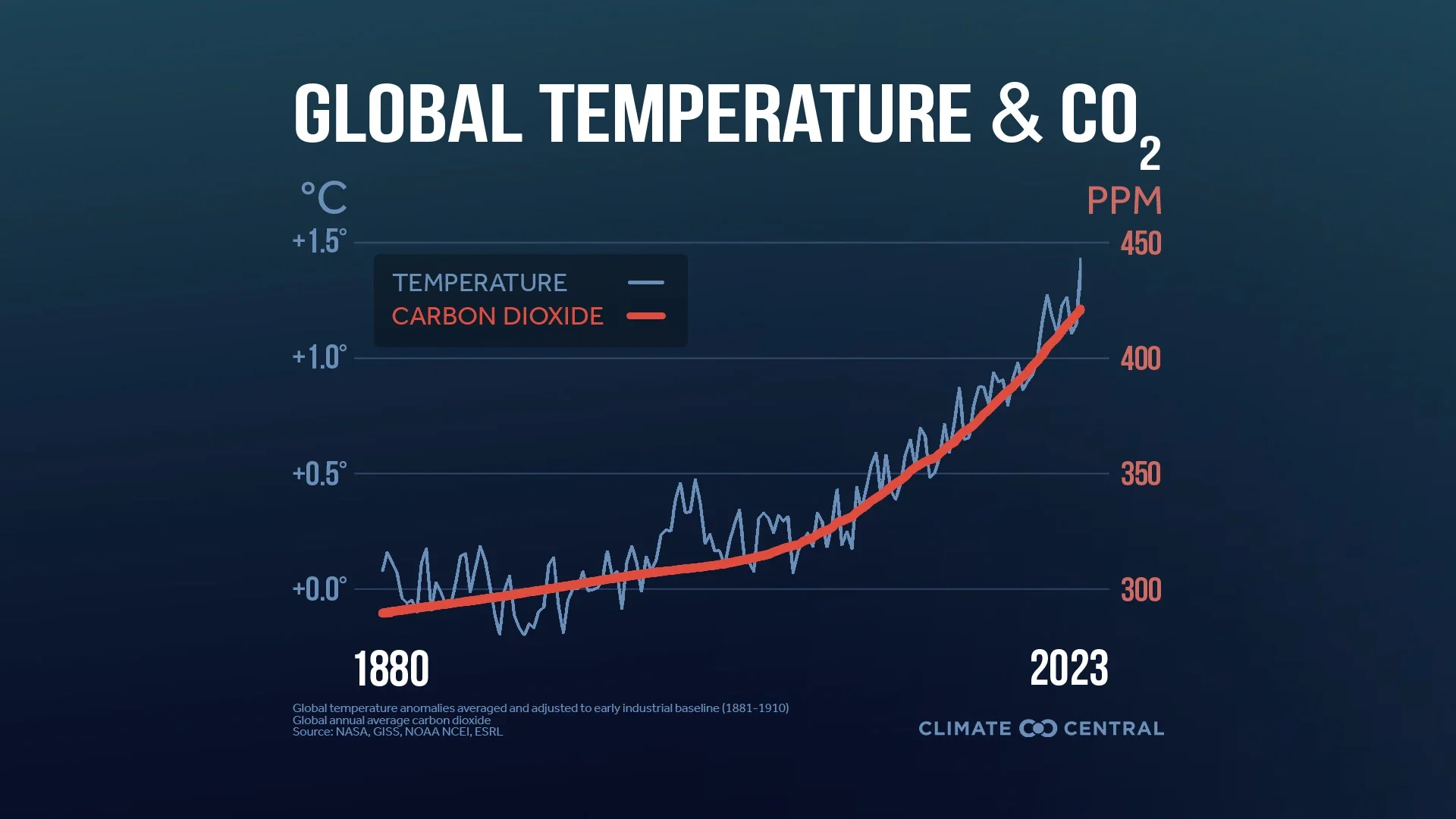

According to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the global temperature has risen by ~1.3°C since 1850. This is correlated with a number of adverse effects observed across the world. Extreme weather such as heatwaves, wildfires, droughts, and storms has become more frequent, more prolonged and/or more severe. The melting of glaciers and ice sheets have dumped excess water into the ocean, causing the sea level to rise. The acidification and warming of the oceans have cause the bleaching of coral reefs and disrupted marine ecosystems. Food and water scarcity has led to mass migration crises and triggered political conflicts. The rise in temperature has caused great alarm among scientists and spurred pleas to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases worldwide, which has been identified as the primary culprit.

There is a common sentiment among climate change deniers that rising global temperatures are actually the result of these Milankovitch cycles. Can Milankovitch cycles explain natural, long-term swings in climate across Earth’s history? Yes. Can they explain the warming climate crisis happening now? This cannot possibly be the case.

Milankovitch cycles are based on very well-understood physics and are highly predictable. Therefore, we can calculate the effects of those changes across incredibly long time periods. The explanation boils down to two main problems, and they are rather simple once you know what Milankovitch cycles are:

First, the timescales that Milankovitch cycles work on are completely different. The change in the eccentricity of Earth’s orbit? The change in obliquity and precession of Earth’s axial tilt? These happen over time periods that span tens of thousands to hundreds of thousands of years. The rapid rise in global temperatures we are seeing now has occurred over just the span of a few hundred years. This is the difference between one second and almost ten minutes. It is simply happening far too fast for Milankovitch cycles to be responsible.

Second, the current trends in the Milankovitch cycles suggest that we are in a long-term cooling period (when ignoring all other factors). The eccentricity of Earth’s orbit and the obliquity of its axial tilt are both decreasing, which would factor toward milder seasons. The precession of Earth’s axial tilt currently puts summer closest to Earth’s aphelion (furthest from the Sun) and winter closest to Earth’s perihelion (closest to the Sun). This too would factor toward milder seasons.

So, if Milankovitch cycles suggest we are in a cooling period, why is Earth is still getting hotter?

Since the Industrial Revolution, emissions of greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide have exploded. Since 1850, human activity has caused 2,500 gigatons of carbon dioxide into Earth’s atmosphere. This mostly occurs via fossil fuels (coal, oil, natural gas, etc.). This is a problem because greenhouse gases are very good at absorbing and trapping heat. When energy from the Sun reaches Earth’s surface, a lot of it is reflected back out into space. Greenhouse gases prevent a significant portion of this from happening. Unlike Milankovitch cycles, this rise in greenhouse gases correlates very closely with the rise in global temperature.

It should be understood that greenhouse gases have natural sources and at appropriate levels are actually good for the climate. They keep Earth at a comfortable temperature (as far as we are concerned) and without them, the planet would be too cold for many species to live on. However, modern levels of carbon dioxide in Earth’s atmosphere are higher than at any point in at least the last 800,000 years. Not only that, but it’s being pumped into the atmosphere at an unprecedented speed. This causes severe disruption in the climate’s ability to regulate and adapt. If a car hits a brick wall at 3 mph, it’s not going to be all that eventful. It’ll buff out. If it hits that same wall at 60 mph, it would be catastrophic and the people inside the car are not destined for a good time.

Milankovitch cycles reveal Earth’s place in the solar system to be incredibly dynamic and complex, the result of many variables acting upon it. In many ways, they are an extension of the elegant ballet choreographed by gravity and the frailty of Earth as we have known it. We must always remember that the only constant is change.