Why Closer Isn’t Always Clearer

by Sam Atkins

Technology is advancing rapidly. Modern space telescopes can capture stunning, high-resolution images of galaxies millions or billions of light years away, which leads many to wonder why they struggle to bring out the same detail in some objects found in our own solar system? It feels counterintuitive, but the answer is actually pretty straightforward.

NOTE: Tap or hover over images for captions and credits.

Before we address the question at hand, let’s clarify a crucial aspect of astronomical observation: angular size.

The cosmos is vast, but size in space is all about perspective. An object’s physical diameter, how wide it is from end to end, is fixed. Yet, its apparent size shrinks with distance. That’s why astronomers sometimes describe celestial objects by their angular size, the amount of sky they occupy, rather than their true size.

Imagine tracing a full circle around the horizon: that’s 360° of sky. If something has an angular diameter of 1°, it takes up 1° of that circle. The Moon is a good example. It’s 3,475 km across, about a quarter of Earth’s width, but it appears only about 0.5° in angular size because it sits roughly 384,400 km away. The Moon always stays relatively the same distance as it orbits Earth.

Angular size follows a simple rule: it’s inversely proportional to distance. If you double the distance, its angular size is halved. For finer measurements, each degree divides into 60 arcminutes, and each arcminute into 60 arcseconds (that’s 3,600 arcseconds per degree).

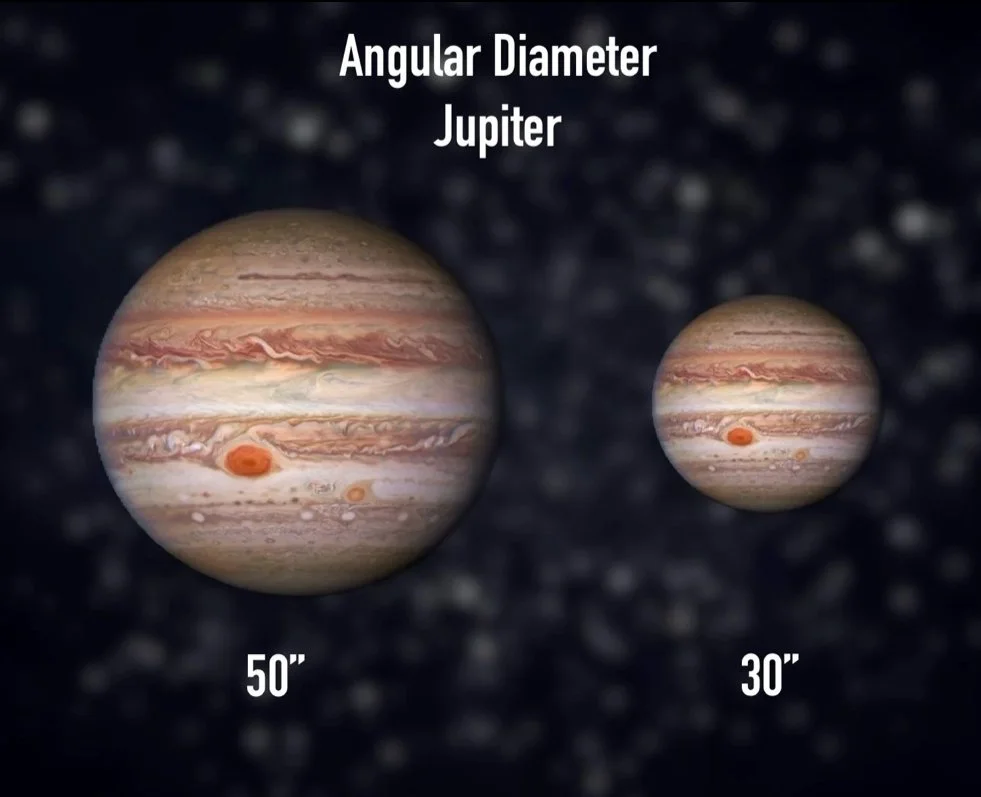

Planets orbit the Sun and can vary greatly with distance. Let’s look at Jupiter (shown above). At its most distant, on the far side of the Sun, it appears 30 arcseconds wide. That’s half of one arcminute. At its closest, it grows to 50 arcseconds!

When it comes to the resolving distant astronomical objects, there’s two sides to the equation to consider: the observer and the observed object.

The first side of the equation is the observer, or in this case, the telescope.

The smallest angular size a telescope can resolve is called its diffraction limit, which depends on two factors: the aperture (mirror diameter) and the wavelength of light observed. Larger mirrors collect more light and produce sharper images, while shorter wavelengths (like blue light) allow finer detail than longer wavelengths (like red or infrared).

Hubble’s 2.4-meter mirror gives a diffraction limit of about 0.05 arcseconds. Any object smaller than this appears blurred. James Webb’s has a 6.5-meter mirror. That’s almost three times the diameter so naturally it should have a high resolution, right? Yes, however, Webb is primarily an infrared telescope while Hubble focuses more on visible light. This closes the gap between them a bit, and Hubble even excels in the shorter wavelengths. However, Webb’s ability to see through interstellar dust in infrared moves the needle back in its direction. This is all to say, there’s some nuance to consider, but you get the idea.

The other side of the equation is the object being observed.

It’s incredibly difficult for the human mind to comprehend the scale of the cosmos. Smaller, everyday units of measurement like kilometers or miles allow numbers to balloon beyond having any meaning. To keep our eyes from glazing over, we try to soften the blow by using astronomical units like light years. However, this sometimes has the opposite effect, making truly vast stretches of the universe feel trivial. We’ll try to explore the size and distance of celestial objects in a digestible way without sacrificing the sense of scale.

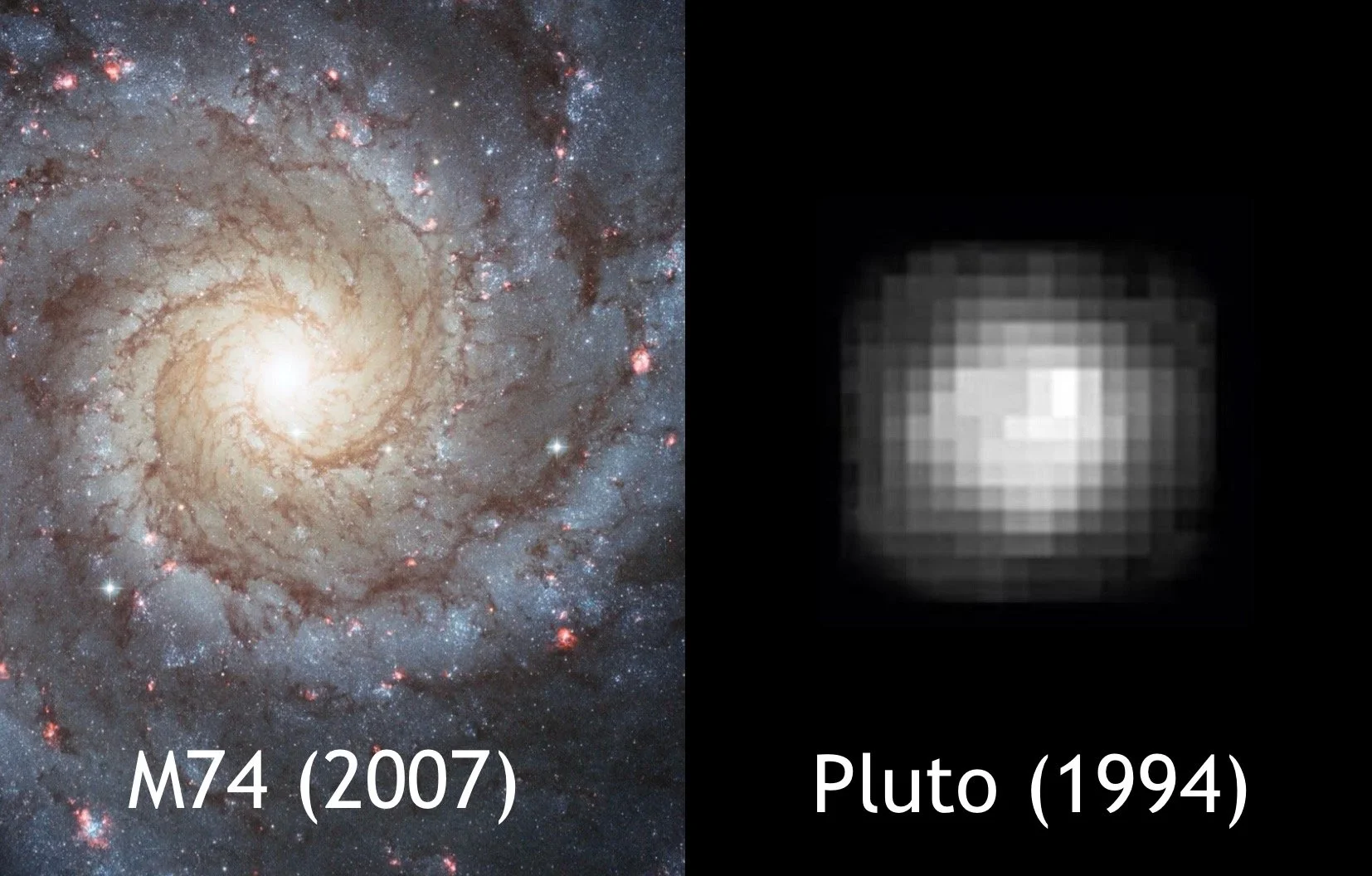

Let’s compare two very different objects: the Phantom Galaxy (M74) and Pluto.

Galaxies are truly gargantuan. Even from 32 million light-years away, the Phantom Galaxy spans about 10 arcminutes across the sky, roughly a third of the Moon’s angular diameter. Compared with that distance, astronomers estimate its true diameter to be about 85,300 light-years. It cannot be overstated how much larger this is than anything in our solar system.

Pluto, by contrast, is just 2,380 km across, smaller than Earth’s Moon. At its current distance beyond Neptune, its angular size is only about 0.09 arcseconds, barely within Hubble’s diffraction limit. Looking at Pluto from Earth is like trying to spot a 2-inch billiard ball in Rehoboth Beach from Bel Air (88 miles away). There’s simply no way even Hubble could make out complex surface features on something that small and that far away. As you can see above, the best it could resolve are contrasts between broad light and dark regions.

This is why distance alone isn’t the key. Angular size, the combination of an object’s true size and its distance, matters far more. Even though the Phantom Galaxy is unimaginably farther away than Pluto, it still appears well over 6,000 times larger in our sky.

The scale difference between the size of our solar system and the size of our Milky Way galaxy (about 100,000 light years across) far exceeds even the gap between the Milky Way and the whole observable universe. If we shrank the distance between the Sun and Neptune down to an inch, the Milky Way would span all of North America. Meanwhile, if the Milky Way were shrunk down to an inch wide, the observable universe would still be only about half the size of Harford County.

At this point, you’re probably asking, “if galaxies are so large in our sky why are they so difficult to see?” Take the Andromeda Galaxy. It spans about six full moons across the sky and lies only 2.5 million light-years away. Yet, through a telescope only its galactic core is clearly distinguished as a faint, fuzzy patch of grey. This is because galaxies are not singular large sources of light but many, many tiny ones spread over thousands of light years. Even with roughly a trillion stars, most of Andromeda’s disk has such low stellar density that each patch of sky contributes very little light, leaving only the densely packed central core bright enough to stand out.

What if the Andromeda Galaxy were much closer? Does that mean it would be much brighter? While it’s true that there would be an increase in its flux (the total light received), the galaxy’s angular size would increase as well, spreading that light across a larger area. In fact, flux and angular area would increase at the same rate (see the inverse square law), basically canceling out each other out. The galaxy would get bigger but not brighter per square arcsecond.

Let’s take a look at another example of this misconception about angular resolution to drive the point home. There is an expectation by some that Earth telescopes should be able to see the objects left behind at the Apollo 11 moon landing site. Once again, the mistake is thinking closer as clearer. It’s the same deal as with Pluto: much closer but much, much smaller.

The descent stage of the lunar lander still remains where Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin left it when they blasted off from the surface in 1969. The body is less than 5 meters wide and its location on the Moon puts it at a distance of 384,400 km. That gives it an angular size of 0.002 arcseconds. That’s so unbelievably small that you’d have an easier time resolving the circular disk of some distant stars, like Betelgeuse. That’s right. A star that is some 650 light years away would appear larger through a telescope than the descent stage of the lunar lander on our Moon. The smallest thing Hubble could see on the Moon would be at least the size of a football field which would appear around as small as Pluto does (and we know how that looks).

The only way we can actually view the various Apollo landing sights is with satellites that actually orbit the Moon. The Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) can get as close as 20 km above the Moon’s surface during its elliptical orbit. Pictured above is an image of the Apollo 11 landing site captured by India’s space agency with their Chandrayaan 2 orbiter in 2021 from an altitude of 100 km.

It becomes clear when considering the deceptive scale of the universe how a planet-sized object can become tiny and a vastly distant object can remain large. Misunderstanding creates a profound sense of depth when looking at a sky that for most people in the world seems opaque. it also important to remember that as advanced as technology becomes, there still remains limitations and conflicting specialties.