Eye Astronomy #17: Bully for You

by Dale E. Lehman

The unfortunate thing about winter, from an astronomy perspective, is that some of the most brilliant parts of the sky are overhead just when the weather is coldest. Brrrr. But if you bundle up and head outside on a clear night, you can at least catch a glimpse of some celestial wonders before rushing back in for a mug of cocoa.

If you make this brave, if brief, excursion about now, you’ll see well up in the eastern sky the zodiac constellation of Taurus, the bull. Taurus is easy to spot because the “eye” of the bull is the bright red star Aldebaran. Shining at magnitude 0.9, sort of (more on that in a moment), it’s the fourteenth brightest star in the sky. It’s a red giant star, and as are many red giants, its brightness is slightly variable. Historically, it was considered to have varied from magnitude 0.75 on the bright end to 0.95 on the dim end. Modern measurements make the range a bit smaller. In any case, you probably won’t notice the difference with just your eyes. For one thing, the period of variability is rather long, around 18 days if not longer. Also, the variations are irregular. I’ve never been able to tell the difference, myself.

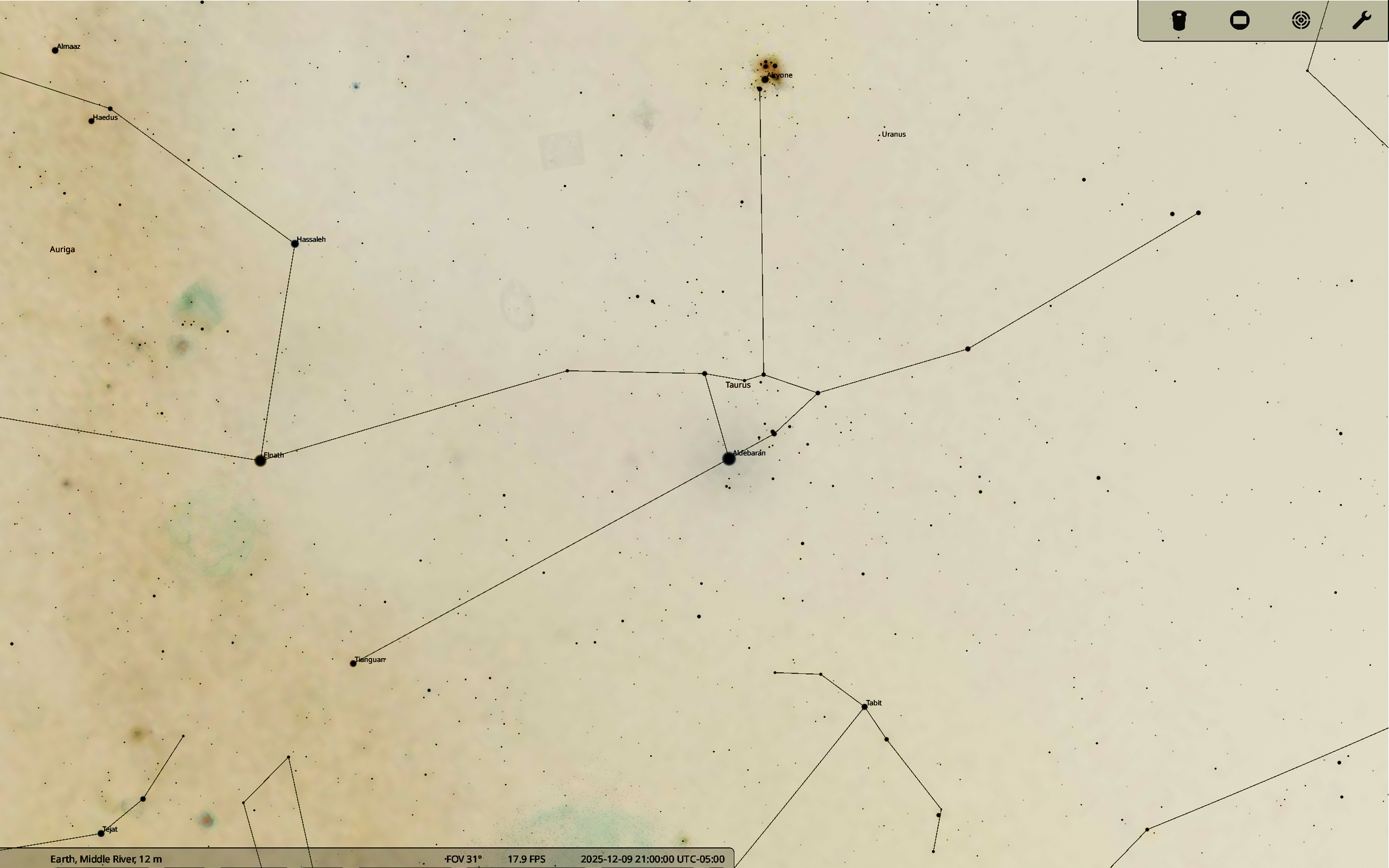

Taurus, the bull. Aldebaran is the bull’s eye. The Pleiades are up, the Hyades are next to Aldebaran.

Still, Aldebaran is bright and distinctly red. Also, it’s placed near two of the most remarkable star clusters in the sky: the Pleiades and the Hyades. Open star clusters are groups of stars that were born together but haven’t yet had time to drift apart. Often, the members of a cluster are hot, bright, and very young, but not always. The Pleiades certainly are, because they’re only around 100 million years old, on the baby end of stellar lifetimes. The Hyades? Not so much. They’re 600 to 700 million years old, which still young compared to our sun (4.9 billion years old!) but not exactly infants anymore.

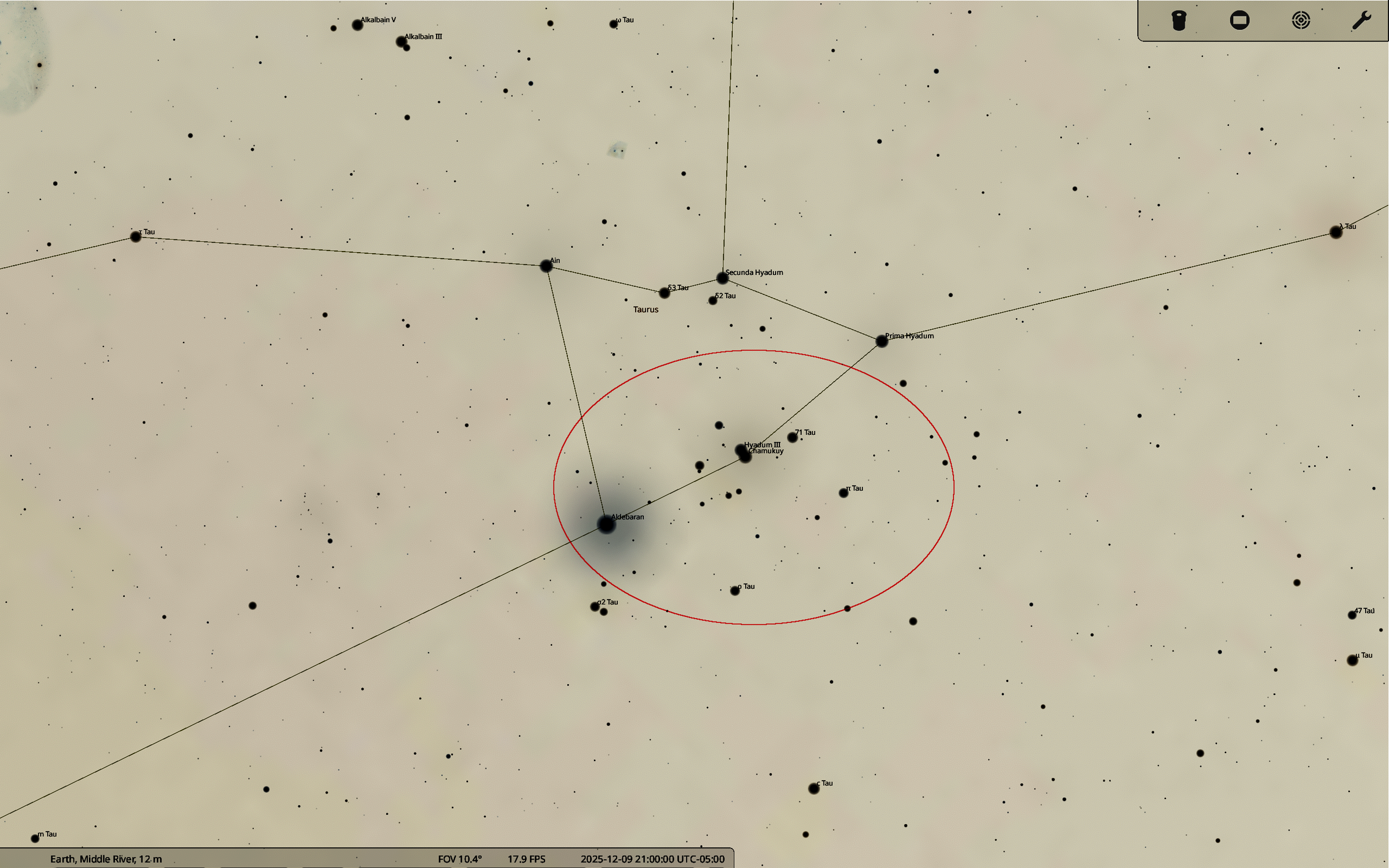

In the above graphic, the Pleiades lie above (west of) Aldebaran, while the Hyades are right next to it. Let’s take a closer look at the latter cluster, marked roughly by the red ellipse:

The Hyades, roughly in the red ellipse.

You’ll notice that from Aldebaran, a sort of “V” of stars spreads to the right (south). It looks very much like the bull’s eye is part of the cluster. But appearances can be deceiving. Space has depth. A lot of it. Aldebaran lies just 67 light years away, whereas the stars of the Hyades are a bit over 150 light years distant. It’s a chance alignment, in other words, but a pretty one. Despite being over twice the distance of Aldebaran, the Hyades are the closest open star cluster to Earth, which is why they are so spread out in the sky.

The Pleiades, on the other hand, are a compact if bright group. Called “the Seven Sisters” because there keen eyes can see seven stars there, it’s often said to look like a tiny little dipper (not to be confused with the Little Dipper asterism in Ursa Minor). Can you guess how far away this cluster is? It’s 444 light years distant, still close in cosmic terms, but much farther away than the Hyades. I like to imagine what the Pleiades would look like if they were as close as the Hyades. They’d be a stunning sight. We only see six or seven of its stars without a telescope, but the cluster contains around 1,000 members If it were as close as the Hyades, we might see hundreds of them!

Taurus has a couple other interesting features. The bull’s horns extend rather northward. The tip of the westernmost horn (up in the first image), is a star called Elnath. Elnath is pretty bright at magnitude 1.7, and it has the curious distinction of belonging (sort of) to two different constellations. Technically, it’s part of Taurus, but it also is included in the figure of Auriga, the charioteer, and has numerical designations for membership in both constellations. Off the top of my head, I can think of only one other star with that quirk: Alpheratz, which is technically in Andromeda but is part of the Great Square of Pegasus. (I’m sure someone will tell me if I missed any others.)

The other neat thing about Taurus is an object you can’t see with the naked eye. In fact, it’s a challenge to find even with amateur telescopes unless you have reasonably dark skies. It’s the first object in French astronomer Charles Messier’s catalogue of things not to look at, because they aren’t comets: M1, the Crab Nebula. Over 2,000 light years away, the Crab Nebula is a supernova remnant, the remains of a star that exploded in 1054 and was observed by Chinese and Japanese astronomers of the time. (I say it exploded in 1054, but that’s when the supernova’s light, which had been traveling for over two millennia, reached the Earth.) It lies just west of the tip of the other horn, the star Tianguan.

So you see, astronomy is more than science. It’s entwined with history, art, philosophy, and religion, too.