3I/ATLAS: 2025’s Interstellar Visitor

by Sam Atkins

You’ve likely seen images of an interstellar comet plastered all over your social media feeds for the last handful of months and heard all manner of things about it. As this incredibly rare object reaches its closest distance to Earth, let’s take a closer look!

NOTE: Tap or hover over images for captions and credits.

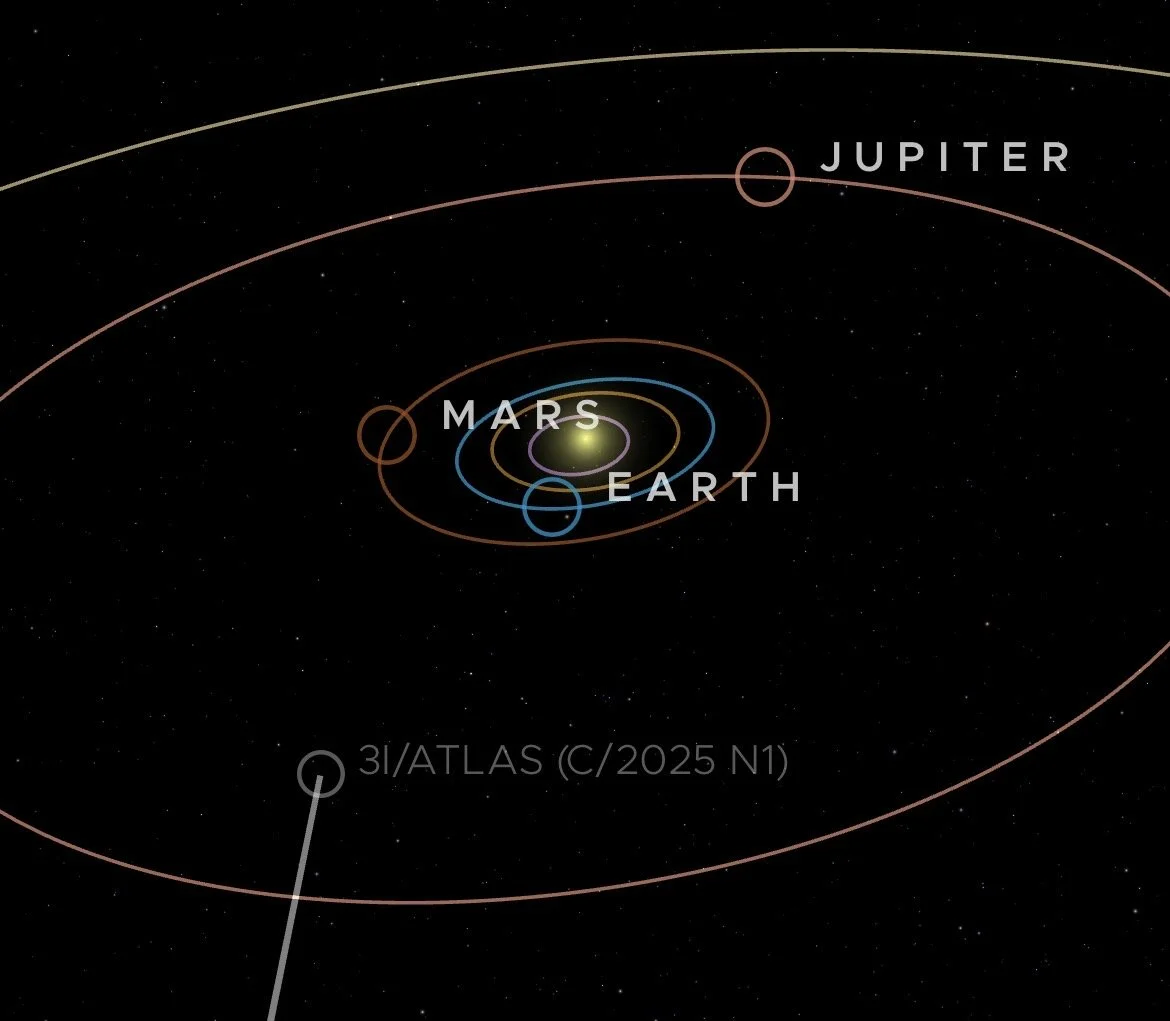

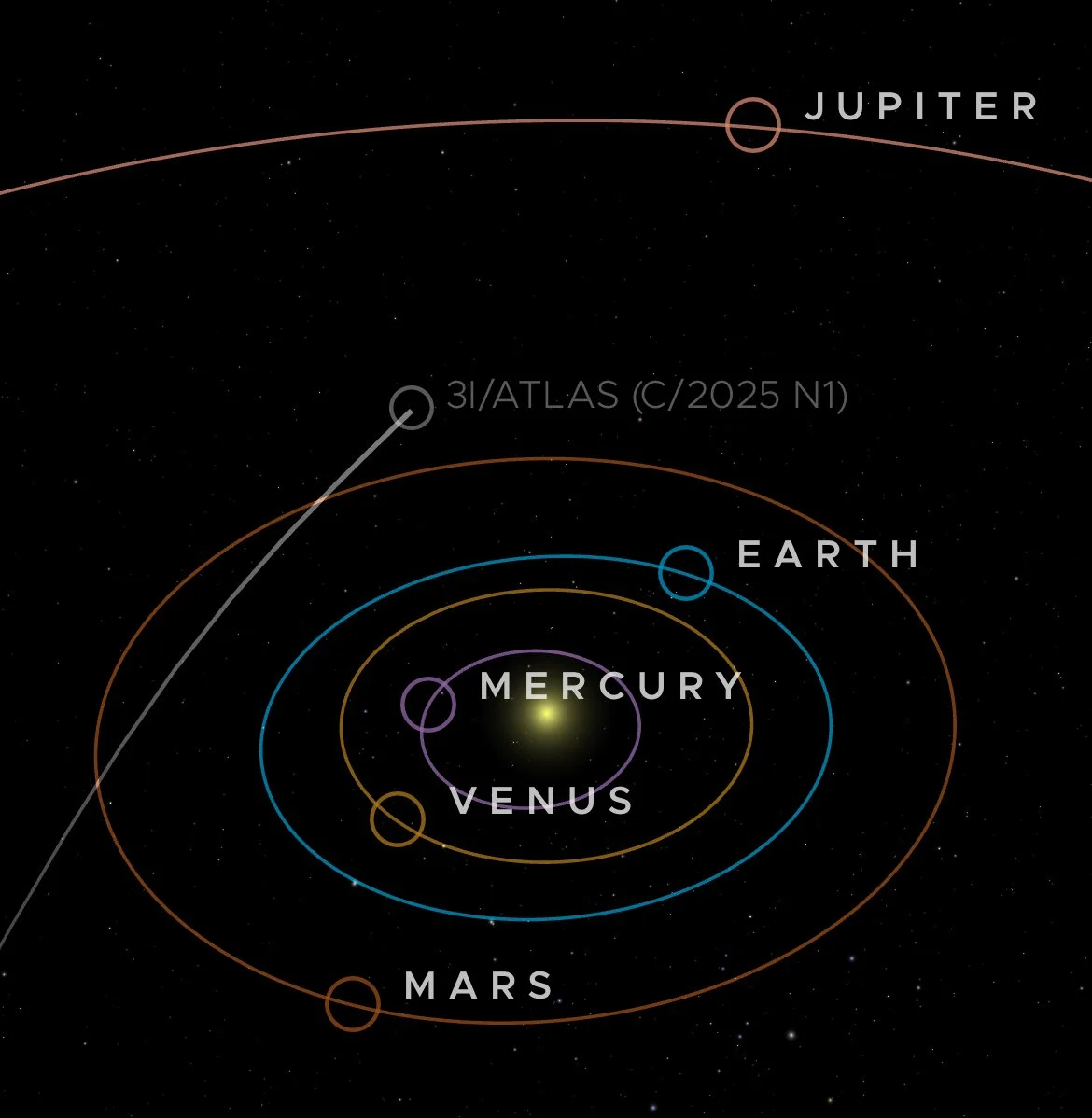

On July 1st, 2025, a NASA-funded ATLAS (Asteroid Terrestrial-impact Last Alert System) survey telescope in Rio Hurtado, Chile reported the observation of an 18th magnitude object arriving from the direction of Sagittarius. By the time it was spotted, the object had crossed inside of Jupiter’s orbit, putting it 3.5 astronomical units (524 million km) from Earth. It was very quickly identified to be a comet of interstellar origins. This was based on the comet’s incredible speed of 220,000 km/h and its hyperbolic trajectory, which made it easy to rule out the gravity of any planets or the Sun as responsible for either. Designated 3I/ATLAS, it is only the third known object found in our solar system to have not originated here.

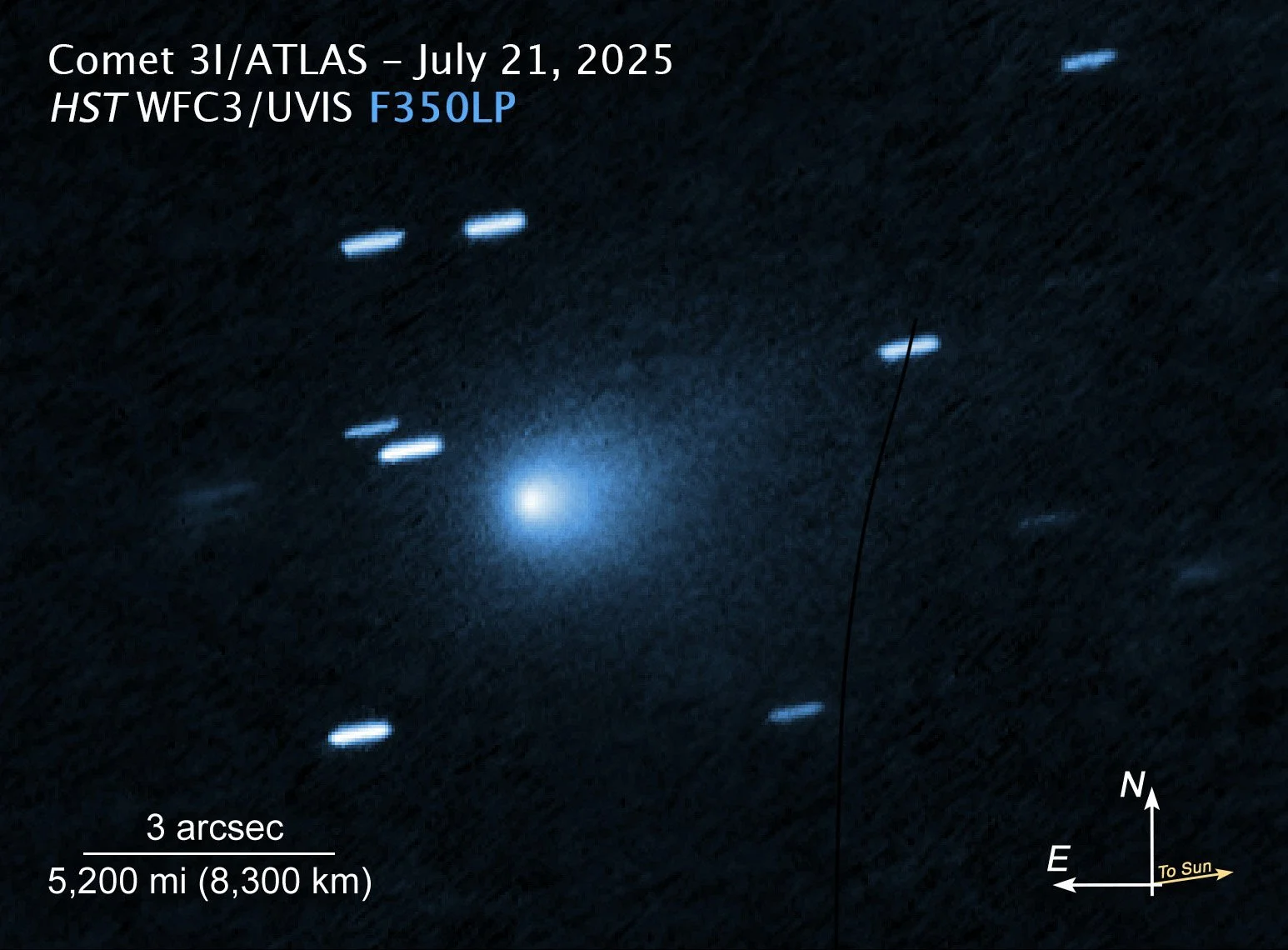

Before we go further into the comet’s journey, let’s talk about the comet itself. As you can imagine, scientists don’t get a lot of opportunities to study an object from beyond our solar system this closely, so there has been a mad rush to learn as much about it as possible.

The first thing you’ll notice when looking at pictures of 3I/ATLAS is its bright, fuzzy coma, an envelope of gas and dust released as solar heating causes ices in the comet’s nucleus to sublimate (turn directly from solid to gas). As the comet has approached the Sun, the coma expanded, and at its peak the coma grew to around twice Earth’s diameter. This dwarfs the comet’s solid core (called the nucleus) which is thought to be only 0.2–5.6 km wide. Solar radiation then pushes this material away from the comet, forming a tail of ionized gas and dust. By September, 3I/ATLAS’s tail had spanned more than 100,000 km into space.

Scientists were able to use spectroscopy to analyze the light from the coma to determine what the comet is made of. Typical of comets is the presence of volatile ices (such as water and carbon monoxide), organic gases (such as cyanide), dust and trace volatiles. Odd is the detection of nickel atoms which have high melting points. They are expected to be found locked inside rocky grains, not free-flowing from icy comets. The most surprising find was an extreme abundance of carbon dioxide, far exceeding water vapor. In comets originating from the solar system, we see water as the dominant driver of activity. This could be more evidence of the comet’s interstellar origins.

The comet is also estimated to be quite ancient, likely older than our own solar system. The comet’s speed and trajectory are consistent with objects that originate from the Milky Way’s “thick disk,” a puffed-up layer of older stars above and below the galaxy’s main plane. If the comet is indeed from that part of the galaxy, it is possibly at least 7 billion years old. This would make it almost twice as old as Earth and the oldest comet we’ve ever seen.

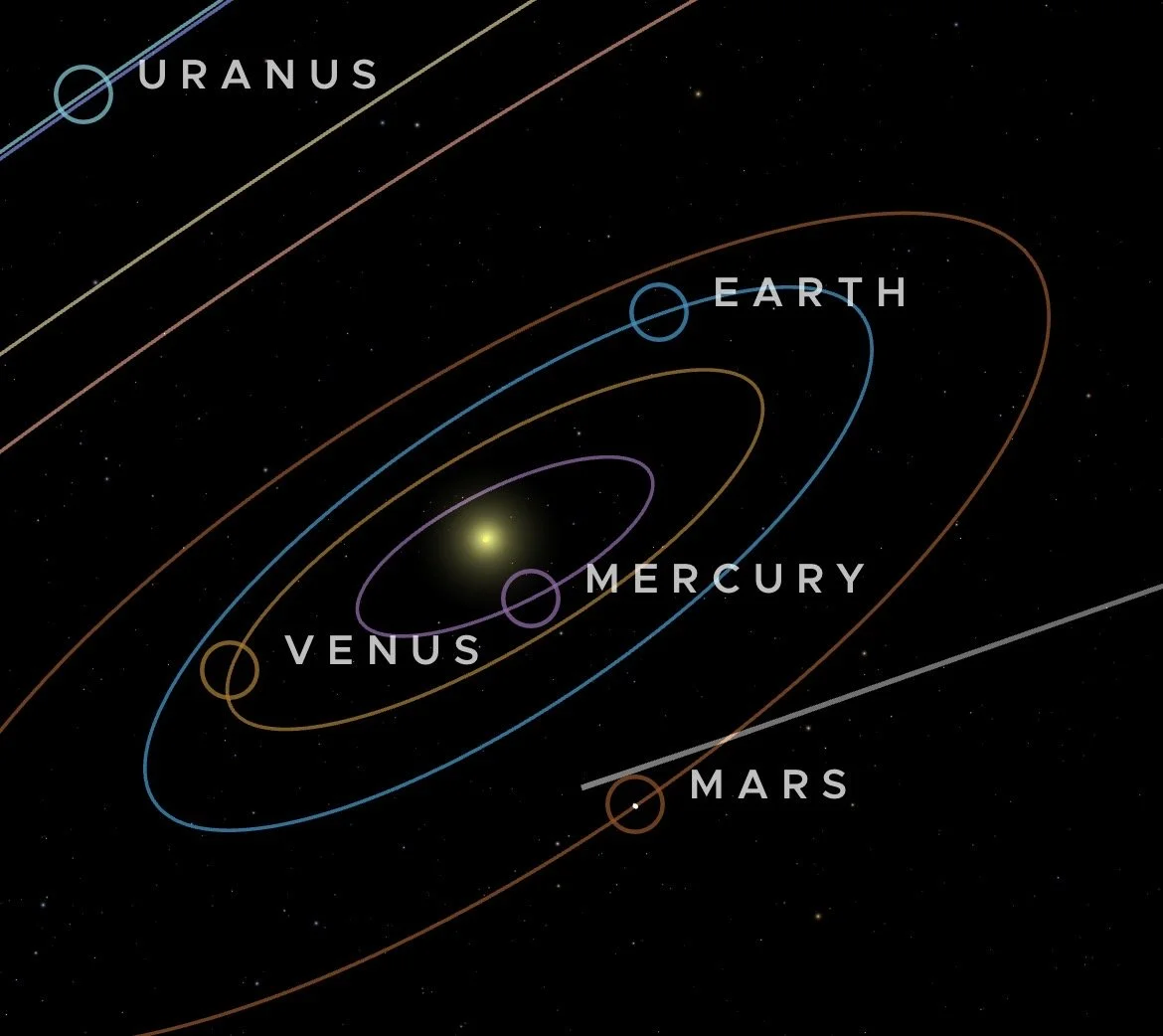

By pure coincidence, 3I/ATLAS’s trajectory is closely aligned with the orbital planes of the solar system’s planets. This has brought it relatively close to many of our space probes spread throughout the solar system. Based on its trajectory, it likely passed within 4.15 AU (623 million km) of the New Horizon’s space probe when it was approaching our solar system back in September 2021!

On October 3rd, 3I/ATLAS made what will be the closest pass of any planet in our solar system, Mars. Less than 0.2 AU (29 million km) above the planet’s northern hemisphere, several Mars orbiters and rovers were able to see and image the comet. By this point, the comet’s already high speed had risen to 240,000km/h due to the growing influence of the Sun’s gravitational pull.

On October 29th, 3I/ATLAS finally reached perihelion, its closest distance to the Sun. This was the climax of what was likely a thousands-of-years-long journey from when the Sun’s gravity first became dominant on 3I/ATLAS’s trajectory through the cosmos. At its closest distance, 3I/ATLAS was 1.3 AU (202 million km) away from the Sun, moving 246,000 km/h. After this point, the comet has been on a one-way track out of the solar system where it is expected to never return. The Sun’s gravity will pull back on the comet and slow its speed to around 209,000 km/h before the speed drop declines quickly. This won’t be nearly enough to prevent the comet’s escape.

However, that doesn’t mean its tour our solar system has ended! It still has months and months before it exits from the planetary orbits and will make a few more important passes along the way!

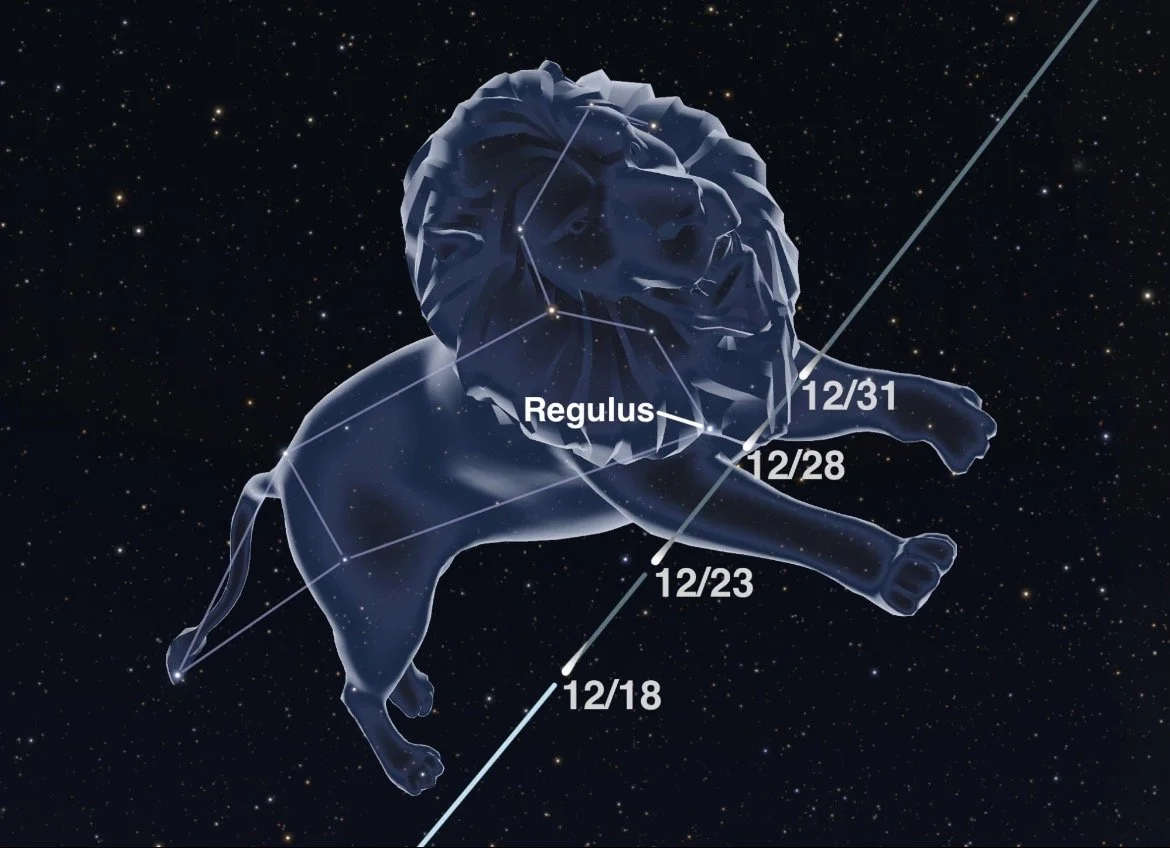

As of December 19th, 3I/ATLAS has reached its closest distance from Earth at under 1.8 AU (269 million km) away. While this is still quite far from us (almost twice as far as the Sun) observation with your backyard telescope might be possible. Through the end of the month, 3I/ATLAS can be found passing through the Leo constellation. You’ll need to wait until around midnight for Leo to get high enough in the night sky to escape the atmospheric interference. To quickly find Leo, find the bright planet Jupiter and trace a line down towards the eastern horizon until you land on Leo’s brightest blue star, Regulus.

On December 19th, from Regulus, trace an imaginary line to the southeast past the blue 4th magnitude star, Rho Leonis. 3I/ATLAS will be about another 4°. Conveniently, on December 28th, the comet will pass very close to Regulus itself. Look just 2° to the southwest of the bright blue star and you should see 3I/ATLAS.

As said before, the comet is pretty far away so keep your expectations in check. You’ll want to wait for the comet to be as high in the sky as you can (closer to pre-dawn hours) and you’ll want clear and dark skies. Good luck!

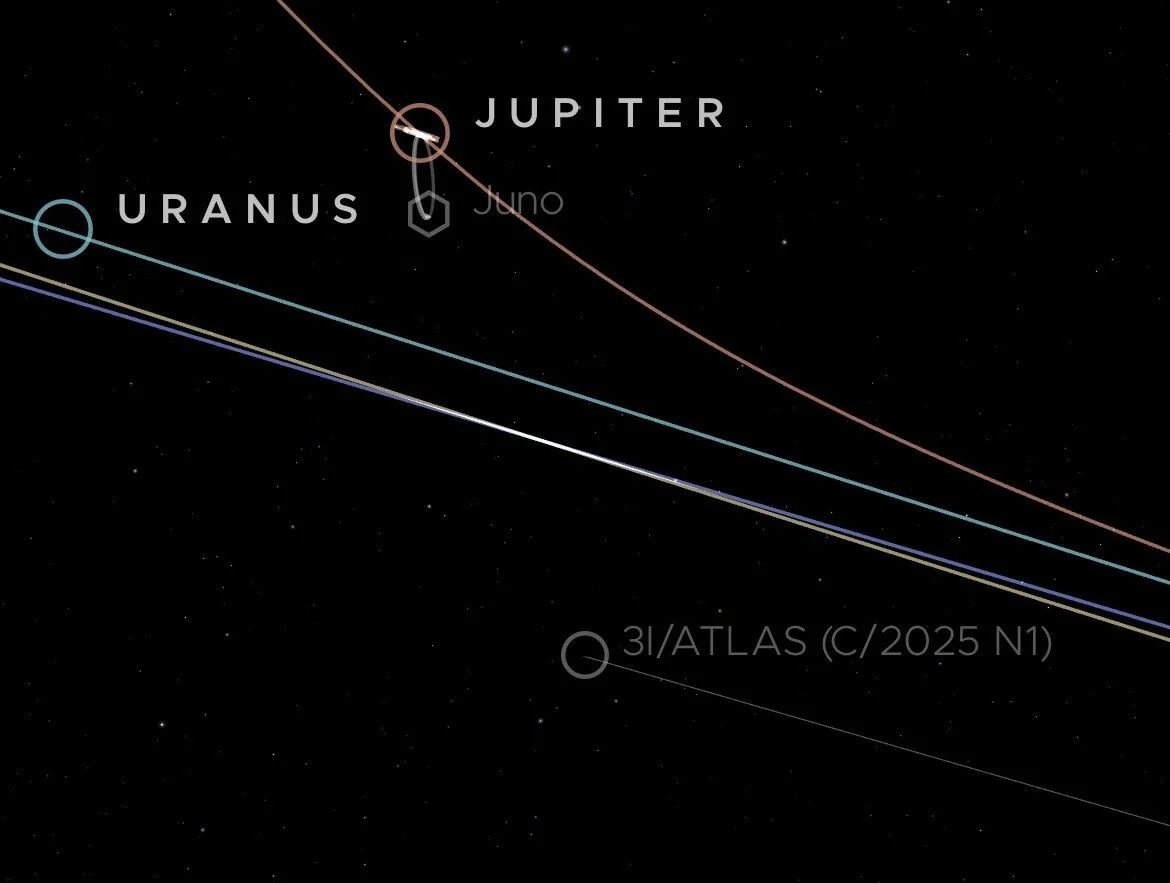

Upon passing the Earth, 3I/ATLAS will continue its long journey out of the solar system and back into the darkness of interstellar space from whence it came. Along the way, it will make one more close pass with another planet, Jupiter. On March 16th, 2026, 3I/ATLAS will pass 54 million km below Jupiter’s southern hemisphere. At this time, Juno, the space probe currently orbiting Jupiter will reach less than 50 million km from the comet. This would be a great opportunity to get another set of close images before the comet leaves forever. However, as of the publishing of this article, the status and future of Juno’s mission remain shrouded in mystery due to the scheduled end of its mission, no word of an extension, and possible 2026 budget cuts. Let’s wait and see what happens!

After the comet’s pass of Jupiter, it will take until 2028 for it to pass the orbit of Neptune and return to the cold and dark reaches of the outer solar system. Its trajectory will have it moving towards the feet of the Gemini twins. Who knows how many more millions of years it will be before this giant iceball will encounter another star system.