MARS

The red planet.

Distance from the Sun: 228 million km (1.5 AU)

Diameter: 6,800 km

Rotation period: 24.6 hours

Orbital period: 686 days

It could be argued that Mars shares more consequential traits with Earth than Earth does with its so-called sister planet, Venus. For one thing, Mars is the only other planet that orbits within the Sun’s Goldilocks zone. It has a comparable axial tilt of 25°, meaning it experiences seasons. Mars rotates on that axis about every 24 hours, similar to Earth. A year on Mars is nearly twice as long but that’s not that much more when compared to the decades to centuries-long orbital periods of the outer planets. There are other interesting examples as well that illuminate what makes Mars such an important planet for the future of humanity’s ventures into space but we’ll come back to that later.

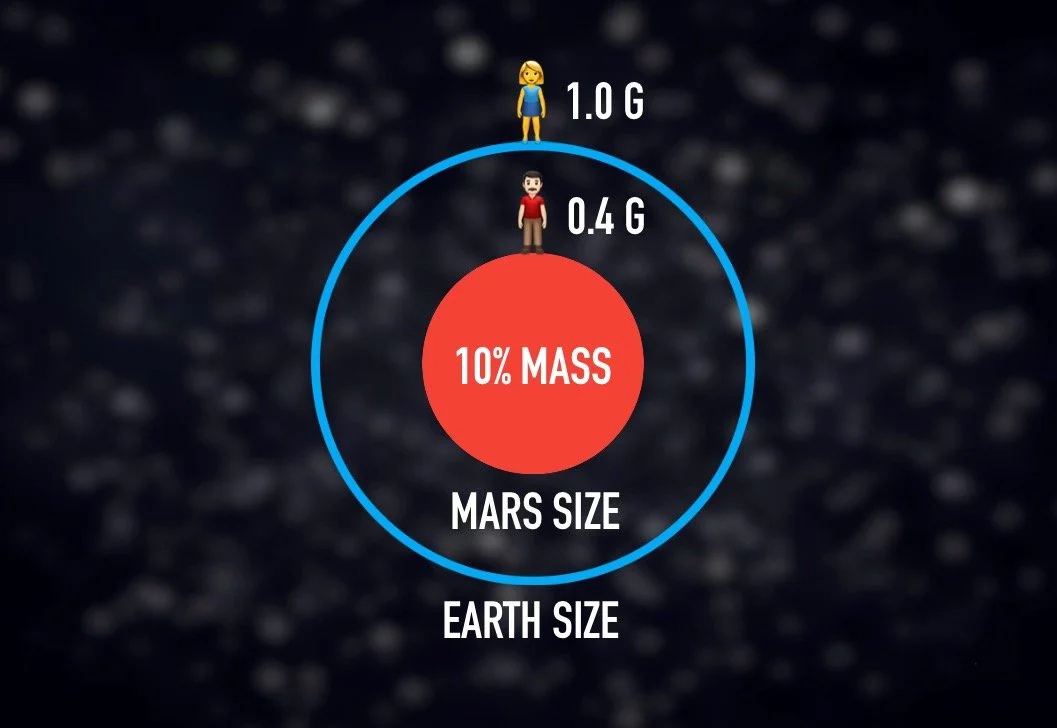

Mars only has about 10% of Earth’s mass and about 40% of Earth’s gravity. But wait… Shouldn’t a planet that has only 10% of the mass only have 10% of the gravity? As we know, the strength of gravity changes exponentially with a square of the distance. If you halve the distance, you quadruple the gravity. Well, Mars is about half the diameter of Earth so the 10% gravity at an Earth-like distance from the center becomes 40% on the surface of Mars.

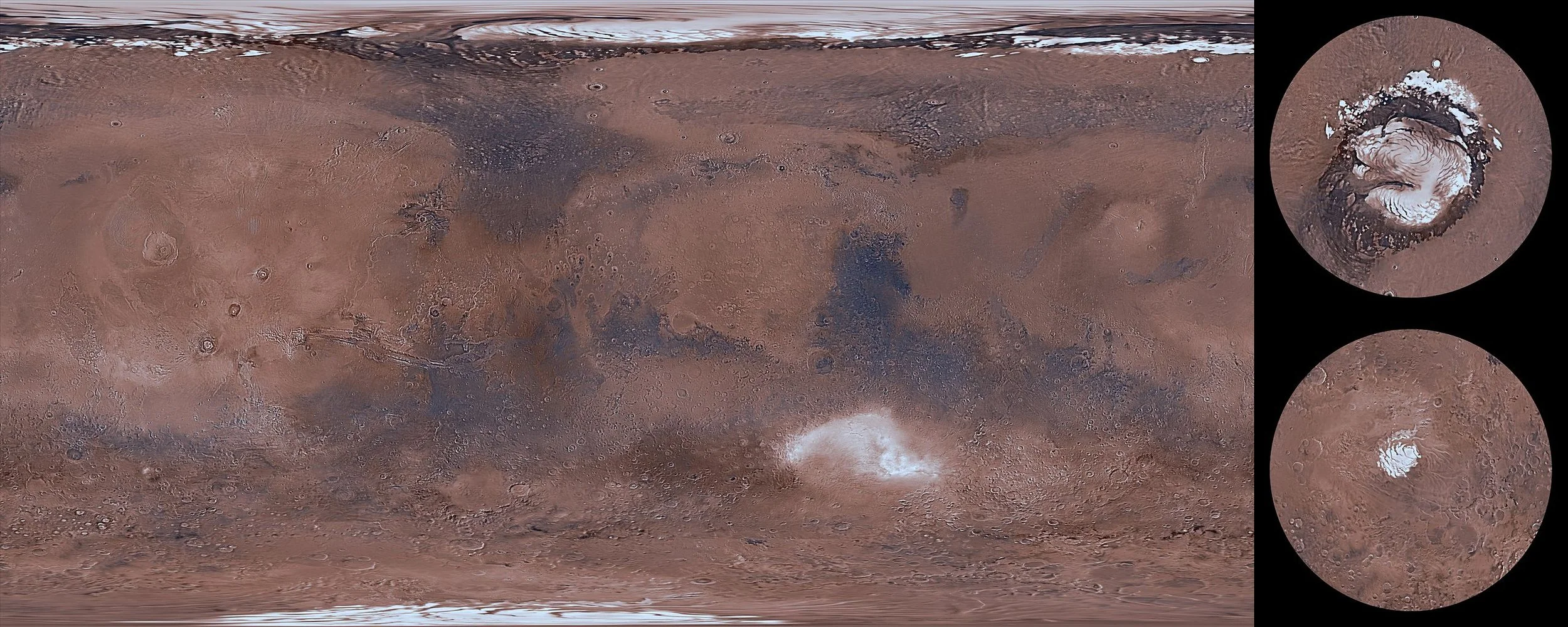

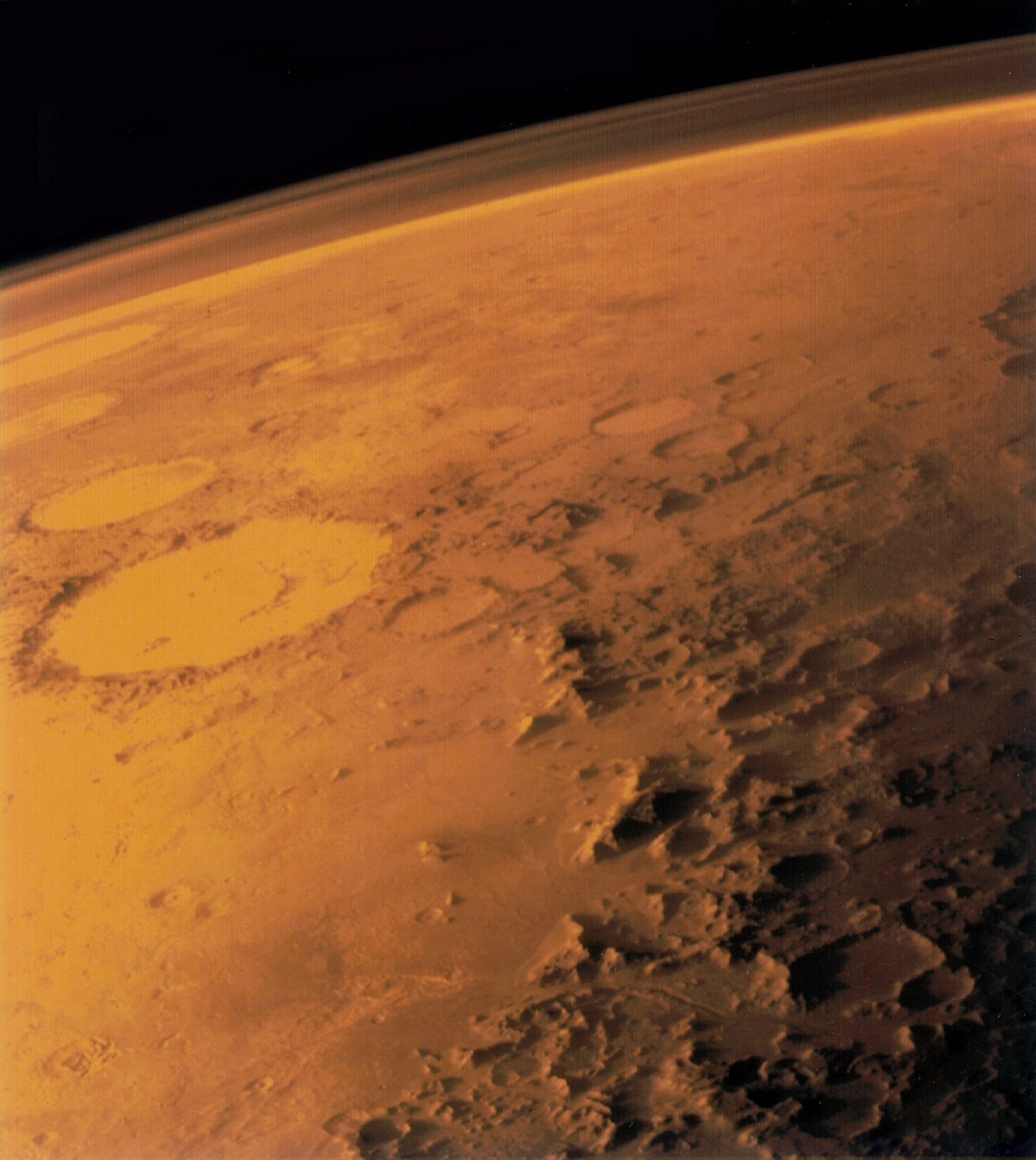

At first glance, the Martian surface appears to be a barren and frigid desert, but we’ve discovered it to be much more as we’ve been able to observe it more closely in recent years. Most of the surface is made up of a gray volcanic rock called basalt covered by a fine layer of iron oxide dust that has the consistency of talcum powder. Iron oxide is largely responsible for Mars’ distinctive red color. This is the same compound that gives blood and rust their hue by absorbing the blue and green wavelengths of the light spectrum while reflecting the red wavelengths. This is also why ancient human observers named Mars after the Roman god of war.

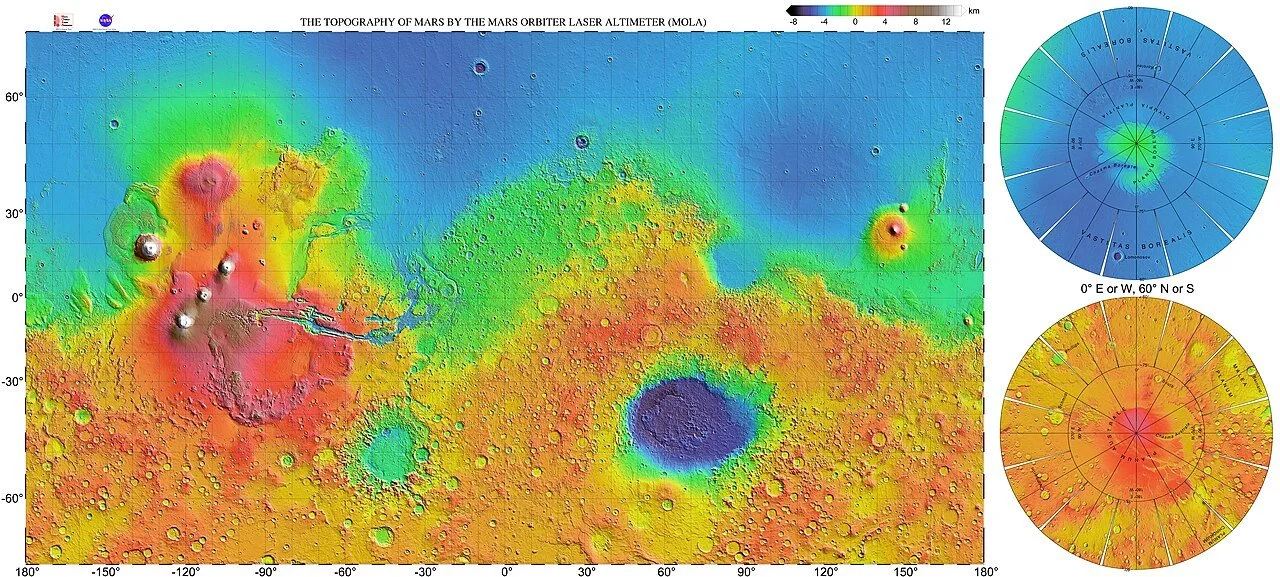

The topography of Mars shows a clear delineation between the northern hemisphere dominated by young, smooth lowlands and the southern hemisphere dominated by old, cratered highlands. The sharp contrast between these two halves is known as the Martian dichotomy.

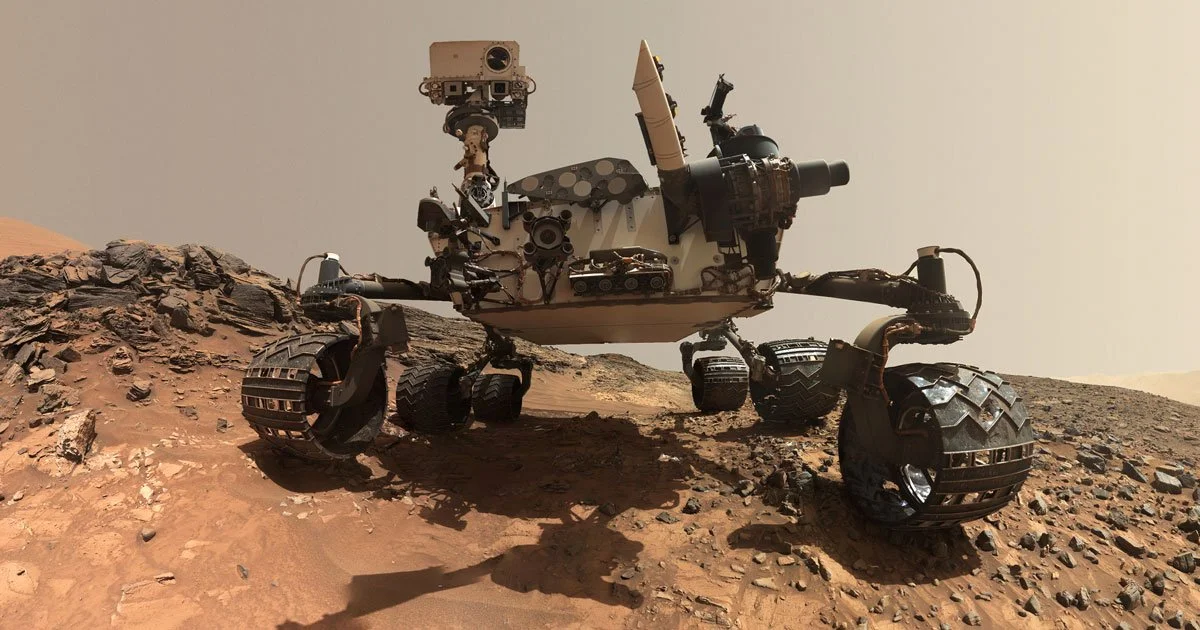

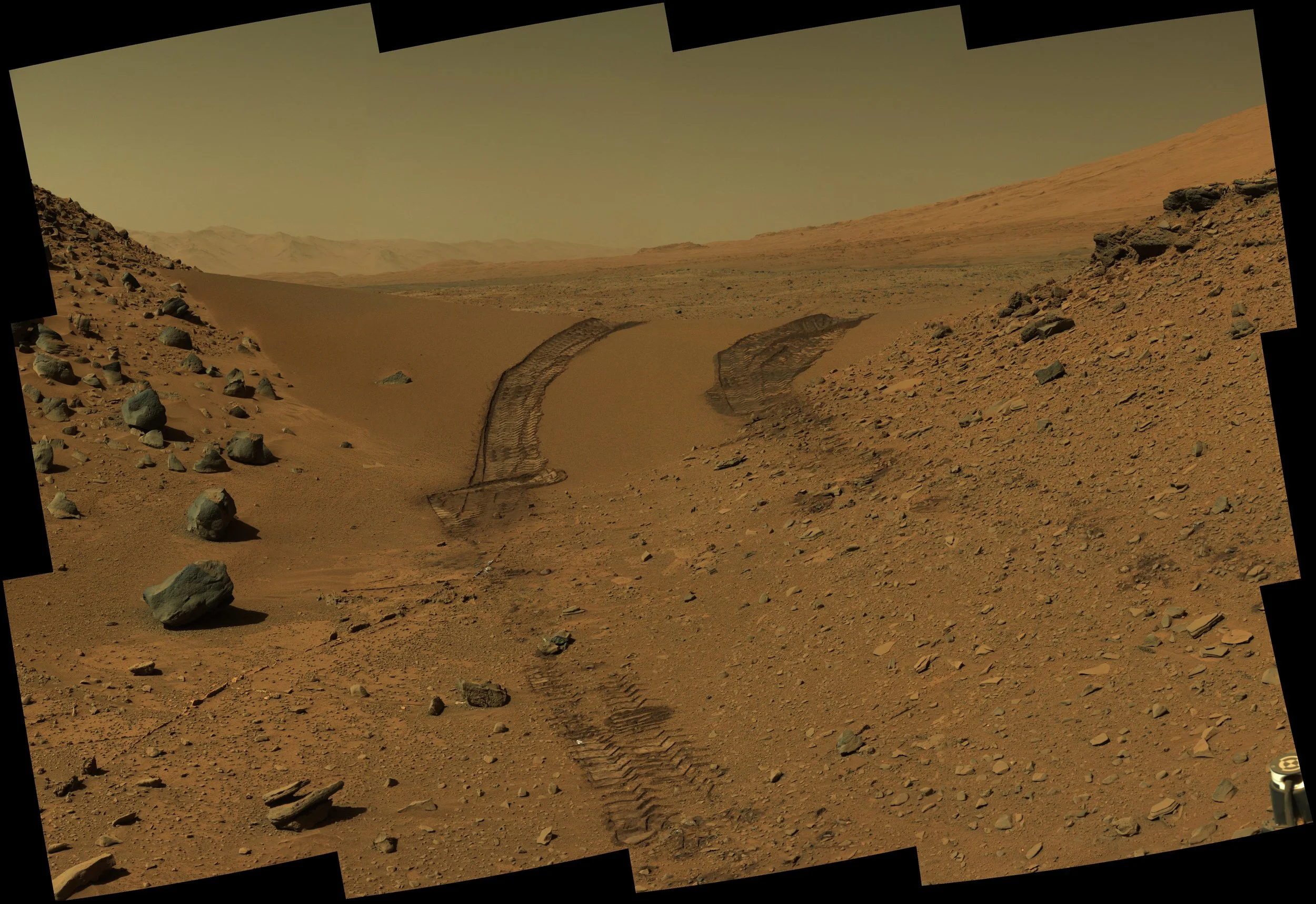

We have had a robotic presence on the surface of Mars for over 25 years, beginning with the Sojourner rover in 1997 and five others since then. There are two rovers currently active on Mars: Curiosity which landed at Gale Crater in 2012 and Perseverance which landed at Jezero Crater in 2021. Using these wheeled remote-controlled vehicles, scientists have taken scores of photos from the dusty Martian surface and transmitted them back to Earth.

Fun fact: Radio transmissions from Mars to Earth take between 4 and 20 minutes at the speed of light depending on their relative orbital positions.

Despite largely being a giant desert, there are a variety of surface features to be found across Mars. A closer inspection of the Martian soil reveals more nuance in its coloration than the red-orange hues seen from space. At ground-level, the surface takes on a more brown and butterscotch color.

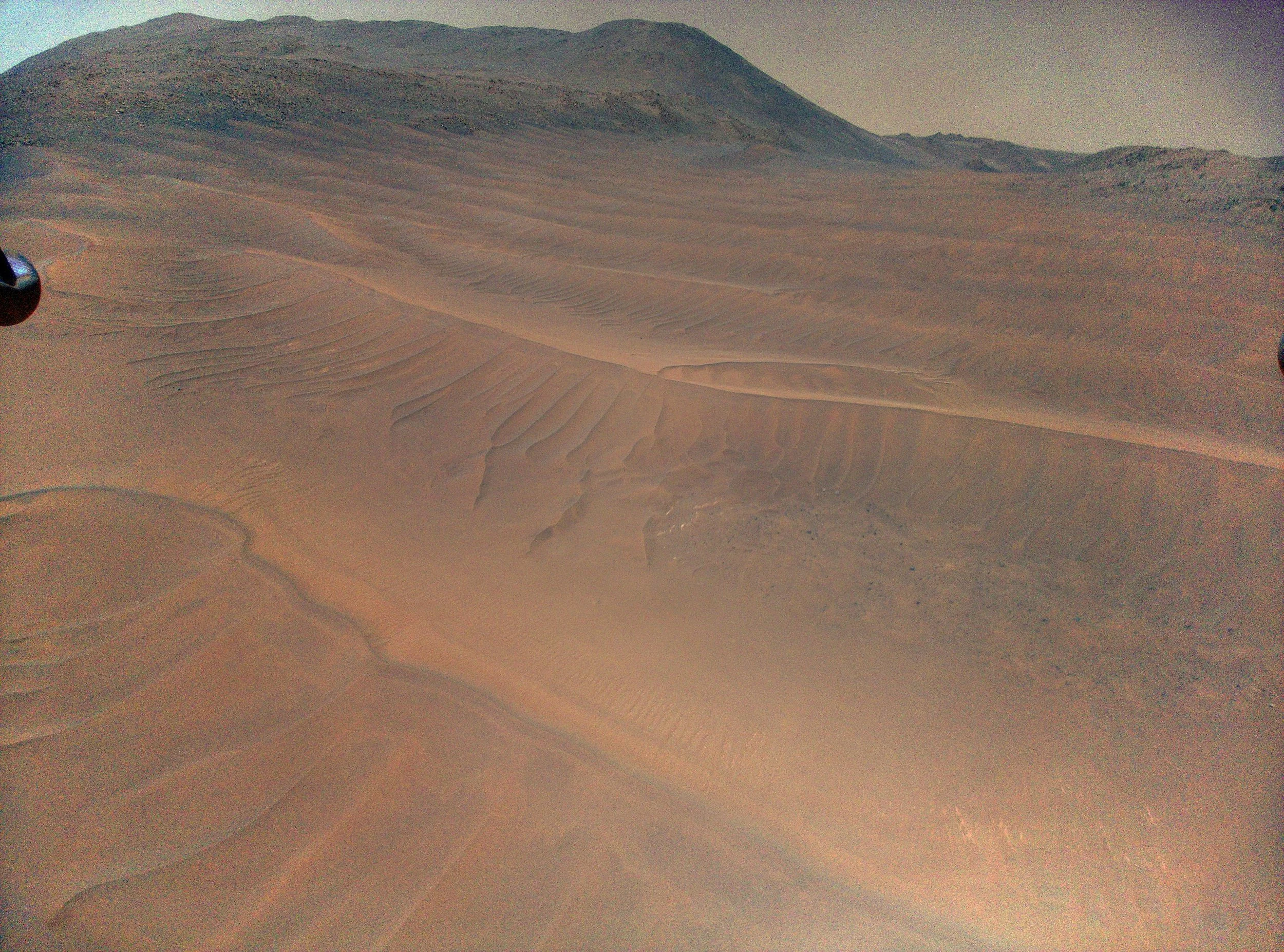

Dunes can be found all across Mars, often by the north pole or inside of large craters. They are seas of sand shaped into wavy ridges by the planet’s wind. Many dunes are black, formed from dark volcanic rock basalt and covered by a seasonal frost. Also common on Mars are numerous canyons and channels that weave and wind across the surface, the latter of which will be discussed in more detail later in this section. Impact craters are featured heavily across the Martian surface due to the thin atmosphere (which can’t burn up as many meteors) and lack of geological activity (which means earthquakes and volcanoes can’t reshape the surface). They are especially prevalent in the highlands of the southern hemisphere. There are millions across the entire planet, ranging from a few meters to a few thousand kilometers across. The largest exposed impact crater on Mars is the Hellas Basin (the deep blue southern region shown on the topographical map above). Volcanoes appear often as well and played an important role in the geological evolution of Mars but have since become inactive. There is evidence of past eruptions galore as much of the surface is covered in hardened lava flows. Some caves have been spotted at the base of the large Tharsis volcano, Arsia Mons. Scientists favor these caves as suitable places for future human research and habitat modules where they will be protected from the harsher elements of the Martian surface.

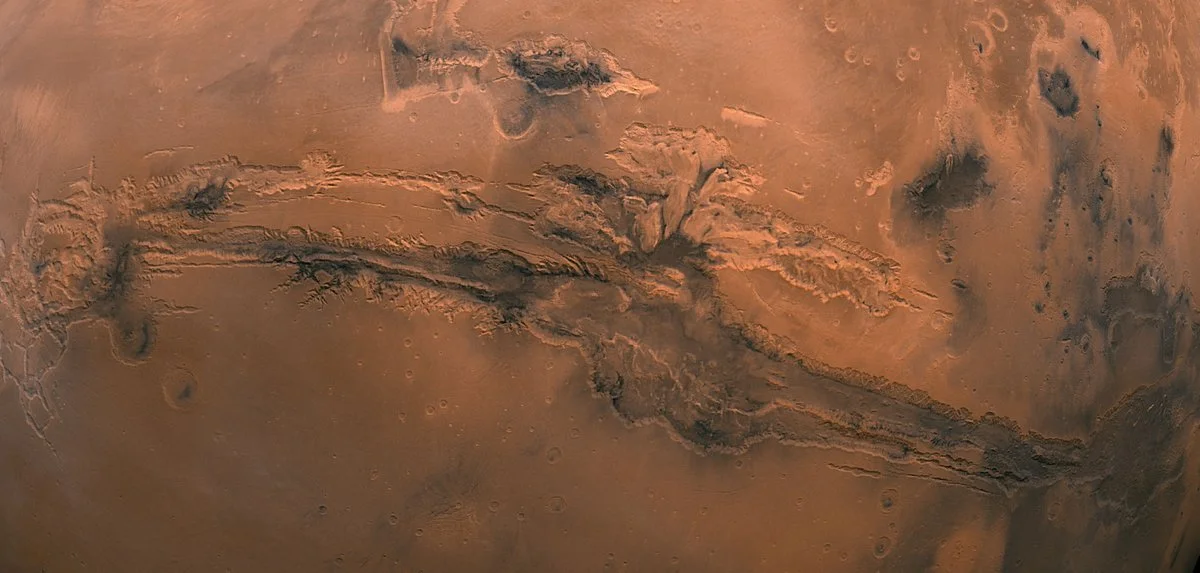

The grandest surface feature on Mars is easily Valles Marineris. Discovered in 1972 by Mariner 9, the first spacecraft to enter into orbit around another planet, it is a gargantuan system of canyons that cuts a wide swath along the Martian surface east of the Tharsis region. At 4,000 km long, 200 km wide and 7 km deep, Valles Marineris is ten times longer and wider than the Grand Canyon. Its size is roughly equivalent to the continental United States.

There have been many ideas proposed for how this great rift formed across a fifth of the planet’s circumference. The prevailing hypothesis is that the rising of the Tharsis bulge created a series of radial stress fractures in the nearby surface. It is also possible that the carving out of the canyons was assisted by various other factors such as subsurface water flooding, lava flows, and acidic glaciers.

The Tharsis bulge is a huge plateau encompassing the most intensely and most recently volcanic region of the planet. This uplifted region is roughly the size of North America. Appropriately, it’s home to the four biggest volcanoes on Mars, including the largest volcano in the solar system: Olympus Mons. This gargantuan shield volcano is about 22 km tall and 600 km wide. It is almost three times taller than Mount Everest and its surface area is roughly equivalent to the state of Arizona. It last erupted about 25 million years ago. This is based on the age of the uppermost layer of hardened lava, determined to be relatively young by the low presence of impact craters.

Mars doesn’t have plate tectonics today, but there’s evidence that it once did. Tharsis was probably over a hot spot, a plume of hotter material rising up through the planet’s mantle. That’s what may have created the bulge, and as the plate slowly moved, the plume punched through the crust to create the chain of three smaller (but still huge) volcanoes.

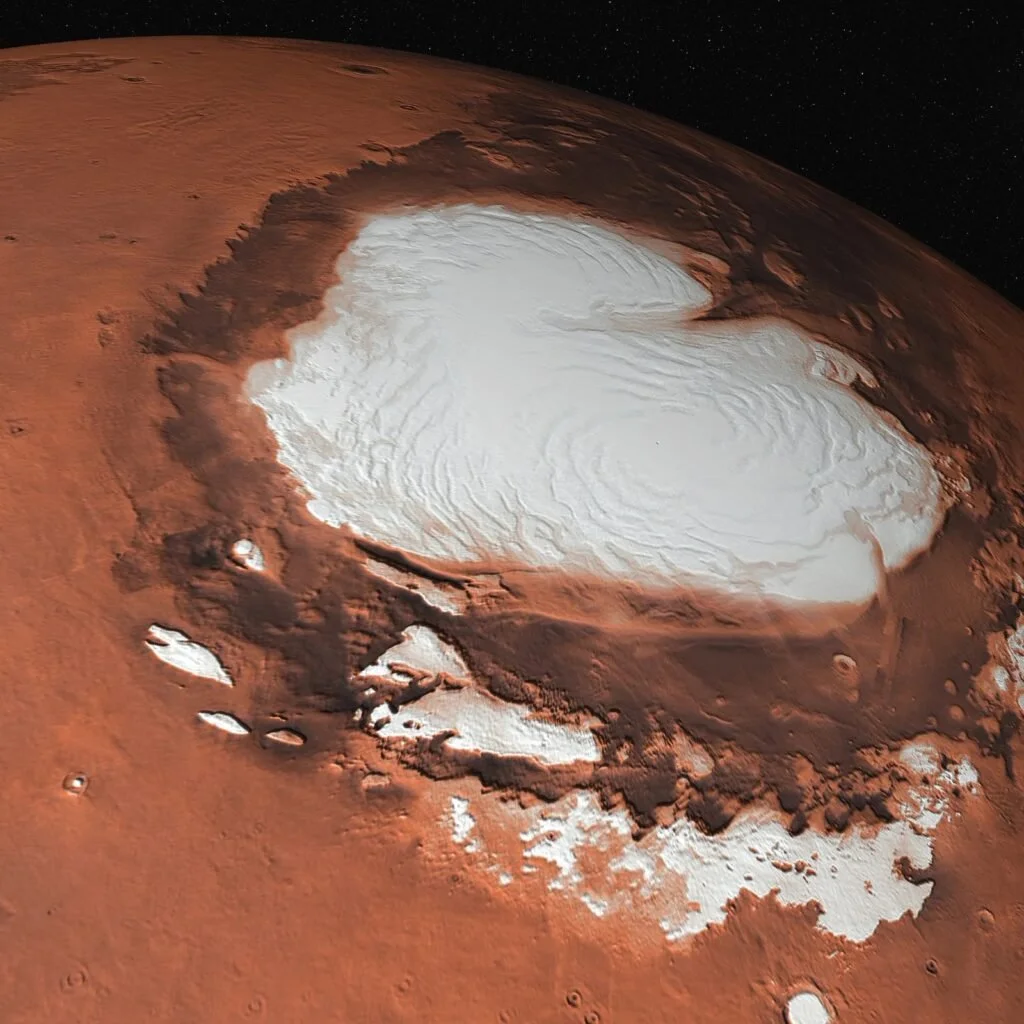

Like Earth, Mars has polar ice caps. Humans have suspected their existence for over 200 years as they are visible from Earth with telescopes. Both have two main layers: a lower residual layer and an upper seasonal layer. The residual layer exists year-round and is mostly made of water ice, several km thick, and mixed with dust and sand particles. The polar caps get seasonal coatings of dry ice, frozen carbon dioxide, that covers them from 1 to 8m thick. This happens in their respective winters; in the summer, sunlight thaws the CO2, causing avalanches and sublimates (turning it directly from solid into a gas) which then blows away from the pole, generating fierce winds.

Ice largely can’t survive the sunlight’s warmth outside of Mars’ polar regions. Ground-penetrating radar and other orbiting detectors have revealed significant subsurface water ice deposits. More than 5 million cubic kilometers (1.2 million cubic miles) of ice has been identified at or near the Martian surface.

While its red and orange-colored deserts may bring about associations with heat, Mars is indeed a very cold planet. The temperature ranges greatly from 70°F to -225°F. This is in spite of the fact that its atmosphere is almost entirely carbon dioxide. On Venus, this results in a runaway greenhouse effect that traps heat and keeps the temperature incredibly high. This is not the case on Mars because, unlike Venus, its atmosphere is relatively thin and lacks the sufficient density to trap heat.

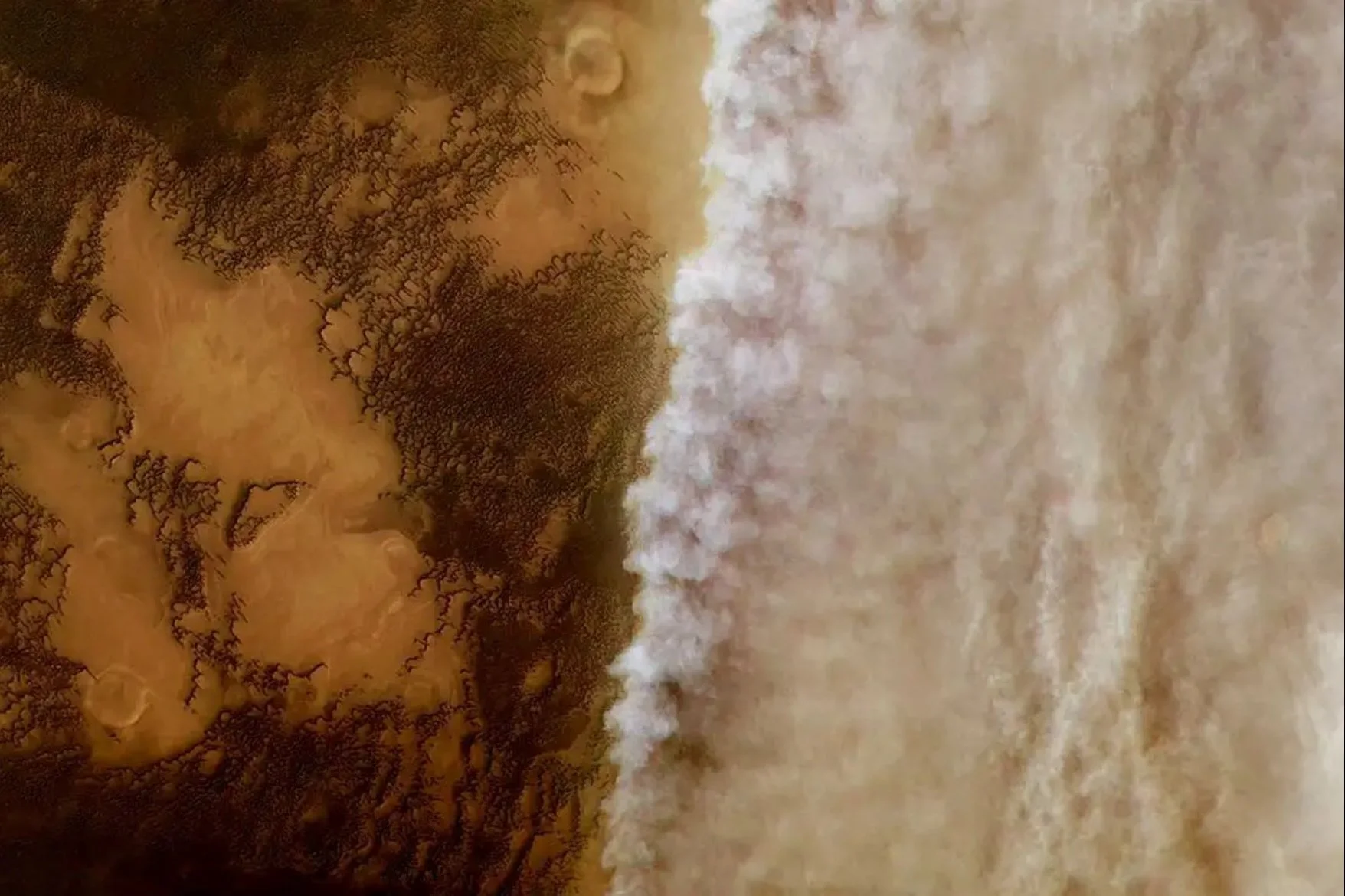

Mars’ atmosphere is only 1% as thick as Earth’s so it is unable to store heat as well and its winds are generally weaker. This can work the other way though. The temperature variations on Mars are much wider than on Earth which can create really strong winds (topping out at 100 km per hour or 60 miles per hour), especially in the morning and evening. Mars has the greatest wind erosion effects in the solar system and can be observed across its various sand dunes. Sometimes these strong wind currents can kick up iron oxide dust forming massive dust storms, some of the largest in the solar system covering continent-sized areas and lasting weeks at a time. Every three Martian years or so, these dust storms can even grow to planet-spanning scales. These dust storms present a significant challenge for engineers of the Mars rovers as the fine dust particles are very sticky and get inside the various nooks and crannies and can obstruct vital solar panels. Convective vortices known as dust devils have also been directly observed, as well as the trails they leave behind in the soil. They form when the warming surface lifts up nearby air and then horizontal winds cause rotation. They are usually many times larger than ones found on Earth with some reaching several kilometers into the sky.

Ice can be prevalent in the Martian atmosphere when much of the polar ice caps evaporate into the spring air. Clouds on Mars consist of water ice and CO2 ice condensed on reddish dust particles suspended in the atmosphere. It occasionally even snows where the snowflakes are made of frozen carbon dioxide cubes.

While Earth’s sky is blue in the day and red at sunset, Mars is reversed, having a red sky in the day and blue at sunset. Why is this? The effects of Rayleigh scattering on Mars is relatively weak because Mars has such a thin atmosphere compared to Earth. The sky’s reddish color in the daytime is more attributed to the iron oxide suspended in the air. There is however a phenomenon called Mie scattering which more effectively scatters red wavelengths of light when colliding with the larger dust particles of Mars’ atmosphere. As the Sun sets and the light passes through the atmosphere at a lower and lower angle, so much red gets scattered that it disappears completely, leaving only blue to be scattered.

One of the most exciting frontiers in the study and exploration of Mars is the search for evidence of water and life. Many images from Mars orbiters and rovers show the red planet to a barren, lifeless world. An endless, frozen expanse of sand dunes, craters and rocks. However, evidence gathered over many years of exploration has mounted and mounted that this is a far cry from what Mars once was. Billions of years ago, when it was relatively young, the surface of Mars is believed to have been covered in liquid water, just like Earth is today.

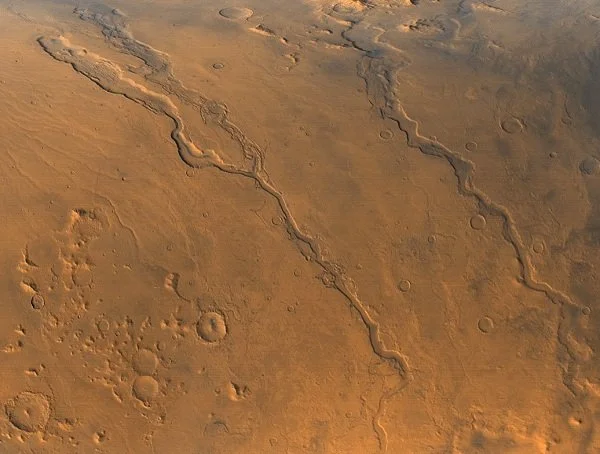

The surface of Mars is covered by many ancient riverbeds, deltas and lakes visible to orbiting space probes that greatly resemble those found on Earth.

Liquid water once carved a complex series of channels through a mix of erosion and catastrophic flooding. Even the 4,000 km-long canyon system, Valles Marineras, is believed to have been formed in part through erosion by water. Many of these riverbeds are still very well preserved due to Mars’ low atmospheric pressure being unable to reshape them through wind erosion. They exhibit many features seen on Earth’s rivers such as terraces, meanders, cut banks and branching networks.

Many can be seen flowing into various impact craters, sometimes through delta formations, where water would have pooled inside and created lakes. The Mars Perseverance rover is currently exploring a delta cutting through the rim of one such impact crater called Jezero Crater while Mars Curiosity rover is investigating riverbeds around Gale Crater. Both are searching for signs of ancient life that may have habituated these areas long ago.

Water erosion

Scientists have found various kinds of rocks and minerals that could have only formed in liquid water, called hydrated minerals.

Lakes of frozen water are found within large impact craters such as the Korolev crater.

Also discovered are peculiar seasonal flows like dark streaks that lengthen down rocky slopes. They are similar in appearance to a phenomenon found in Antarctica called a recurring slope lineae (RSL). They appear in several locations on Mars when temperatures are above -10°F (-23°C), and disappear at colder times. They are believed to most likely be made by liquid moving across, or beneath, the planet's surface.

But if all this liquid water existed, where did it all go?

Billions of years ago, Mars was warmer and had a thicker atmosphere. Water flowed across rivers, lakes and oceans. Deep within, the churning of the planet’s inner iron core produced a magnetic field which shielded Mars from the punishing solar winds. This process is known as a dynamo and is found within our own planet and others. At some point, this churning ceased in Mars. Its internal dynamo shut down and its magnetic field all but disappeared. This left it vulnerable to the solar wind and over billions of years the Martian atmosphere was eroded away and the oceans and rivers dissolved with it. The only water that exists on Mars today, beyond fleeting traces of dissolved moisture, is the water ice in the polar ice caps and below the surface. Having liquid water in the past leaves the possibility (though not the guarantee) that Mars once hosted life. These are currently the most burning questions that scientists are trying to answer.

Mars is undoubtedly the next frontier in manned space exploration. Mercury and Venus are much too hot, and the outer planets don’t have surfaces to land on (though their moons do). Mars is the only other planet in the solar system that is potentially habitable. Robots, the various orbiters and rovers deployed over the years, have been instrumental in learning about the planet. They are cheaper to deploy, more resilient to hostile environments and can operate for long periods of time without many needs.

However, there are certain things that just can’t replace a human touch. Humans can make immediate autonomous decisions whereas long-distance robots require cautious deliberation and consensus. A geologist can quickly identify a rock or complex formation whereas a robot can only take a picture which must be transmitted millions of kilometers where geologists can eventually make sense of the image. Robots designed for specific purposes can’t be modified to meet unexpected challenges while so far away.

There are still many challenges that must be overcome to make a manned mission to Mars not only possible, but fruitful. Considerations must be made regarding a wide variety of aspects of a potential mission including:

The cramped, months-long space voyage (efficient fuel use, prolonged microgravity)

Entry into Mars’ thinner atmosphere is faster (heat shield, deceleration technology)

Rocket that can land and take off for a return journey (can be smaller than Earth-to-orbit rocket)

Providing for the physiological needs of the crew (food, water, air, exercise)

Protection from the elements (solar and cosmic radiation, extreme temperatures, toxic soil, dust storms)

Habitats and research stations on the Martian surface (subsurface caves and lava tubes can better shield the crew from the harsh surface climate)

MARTIAN MOONS

Mars is the only terrestrial planet in the inner solar system other than Earth to have a natural satellite. In fact, Mars has two: Phobos and Deimos.

Phobos

Deimos