Eye Astronomy #13: The Scorpion and the Teapot

by Dale E. Lehman

On high summer nights, a wonderful sight greets the eye. Or it would, if light pollution wasn’t so prevalent. At this time of year, the Milky Way splits the sky, running roughly north to south around 10:00 PM. It’s particularly spectacular from the southern horizon up to the zenith, the point directly overhead.

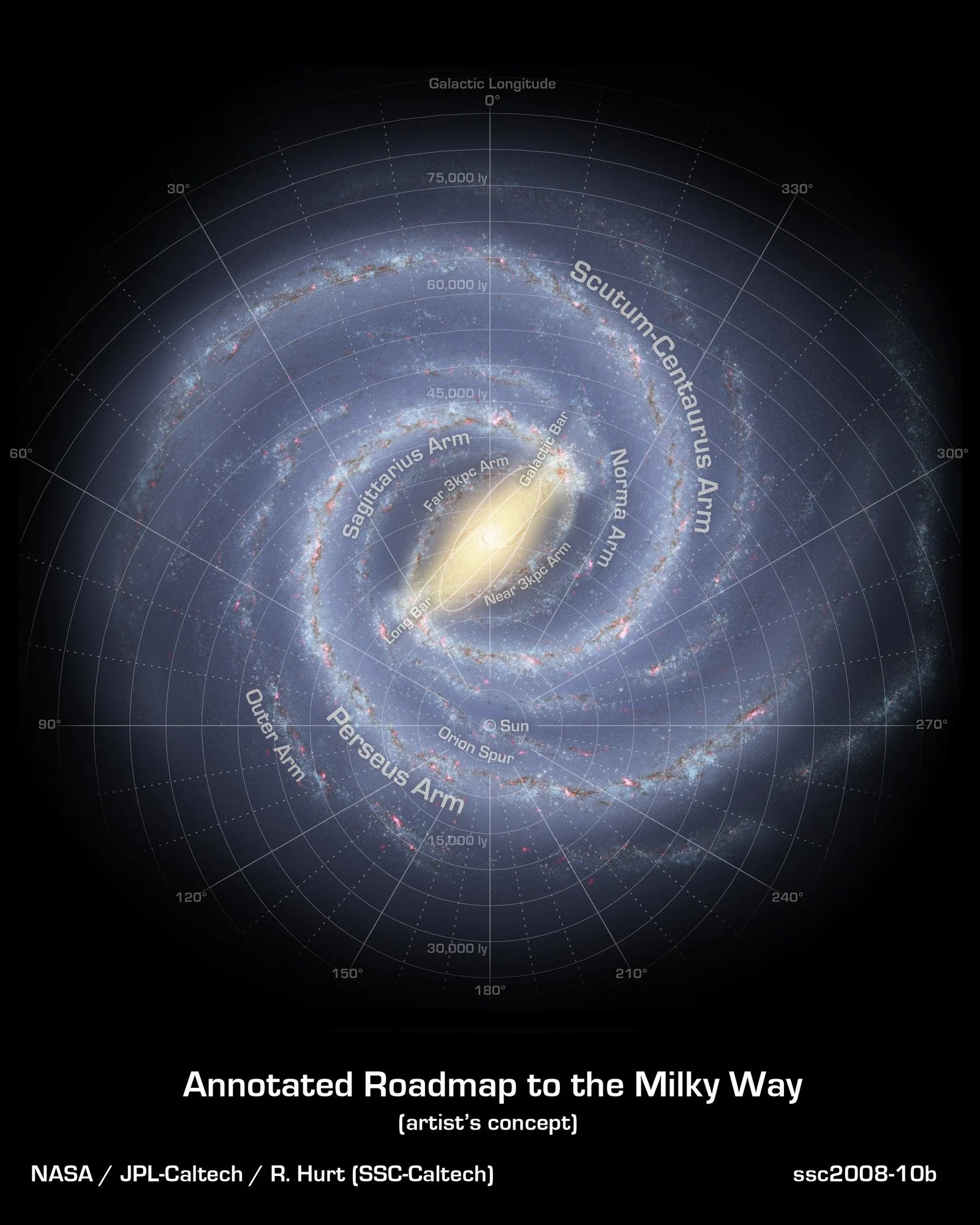

The Milky Way is, of course, our home galaxy. It’s a barred spiral galaxy, which is really cool because ever since I discovered them as a teenager, barred spirals have been my favorite. Back then, we knew the Milky Way was a spiral galaxy, but we didn’t know it was a barred spiral.

Anyway, spiral galaxies, barred or not, can be thought of as enormous swirled pancakes with a bulge in the middle. The band of the Milky Way up in the sky is the pancake. When we look in that direction, we’re looking through the galaxy. When we look elsewhere, we’re looking out of it into intergalactic space. The Milky Way in the sky is simply an enormous accumulation of stars that merge into a fuzzy glow.

That glow is particularly wide and bright when we look to the south at this time of year, if the sky is dark enough. Why? Because that’s where the bulge in the middle lies. That’s the center of our galaxy. You wouldn’t know to look at it, but in the midst of that glowing bulge is something very dark indeed: a supermassive black hole. Twenty-six thousand light years away from Earth, it has a mass of about 4.3 million suns. And it’s hiding inside a teapot.

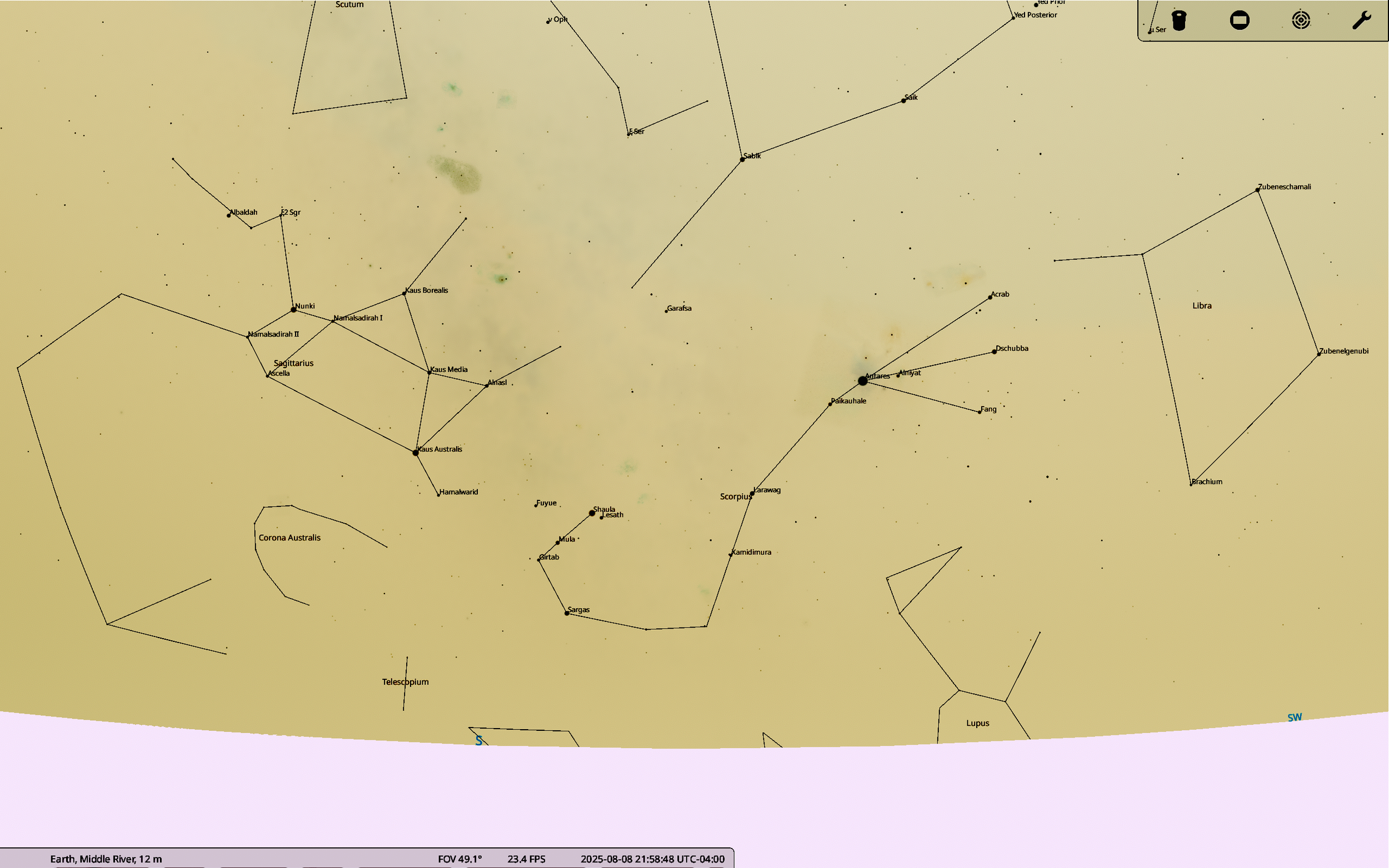

Okay, not literally. But it is in the constellation of Sagittarius, the archer, and there is a well-known asterism in that constellation: the teapot:

I don’t even have to tell you where it is in this chart. You can see it, can’t you? (If not, it’s to the left. Got it now?) You can see that teapot in the sky, too, if the light pollution isn’t too bad. It’s brightest star, Kaus Australis, has a magnitude of 1.75, and the rest are all about in the 2.0 – 3.5 range. The only problem is something called atmospheric extinction, which doesn’t mean the air is dying. It means light passing through the atmosphere is dimmed a little from its encounter with the air. Starlight coming in close to the horizon struggles through more air than starlight pouring down from on high. Stars down low look a bit dimmer—and twinkle more vibrantly—than those overhead.

By the by, that black hole at the center of the galaxy is in a region known as Sagittarius A. It’s not exactly in the teapot. It’s a bit outside the spout, as though expelled in a puff of steam represented by the Milky Way itself. In the chart, look for the tip of the line extending up and to the right from the star Alnasl. That point is a bit above Sagittarius A.

As spectacular as Sagittarius and the adjacent Milky Way are, in suburban skies they are upstaged by another constellation just to the west: Scorpius, the scorpion. Scorpius rather looks like its namesake and contains several stars brighter than Kaus Australis, including the bright red supergiant star Antares, which is just a hair dimmer than first magnitude. Antares is the fifteenth brightest star in the entire sky. Swollen to enormous proportions when its hydrogen fuel ran out and helium burning initiated, Antares has a radius twice the orbit of Mars. If it were placed where our sun is, its surface would be somewhere in the asteroid belt! Not that you’ll be around to see it, but in another million years or so, it will go supernova and could become as bright as the full moon, visible even in daylight.

Antares means “the rival of Ares.” Since ares is the Greek version of Mars, Antares is often called “the rival of Mars.” This designation goes back to ancient times and is no doubt based on the brightness and color of Antares, which does indeed rival that of the planet Mars.

One last point of interest. To the west of Scorpius lies the constellation Libra, the scales. But it wasn’t always there. The Romans added Libra to the Zodiac about 2,000 years ago. Before that, what is now Libra was part of Scorpius. A remnant of that history remains written in the sky. Libra’s two brightest stars have the delightful names Zubenelgenubi and Zubeneschamali, which literally mean “the southern claw” and “the northern claw.”

Whether or not you can see the Milky Way, you probably can still enjoy the teapot and the scorpion on summer nights. Go ahead and hunt them down!