The Apollo 11 Mission (Abridged)

by Sam Atkins

NOTE: Tap or hover over images for captions and credits.

On July 16, 1969, humanity took a bold step forward into the great beyond of the cosmos. NASA launched the Apollo 11 mission which would carry three astronauts to the Moon. Four days later, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin would become the first humans in history to step foot on the lunar surface.

There are two versions of this article chronicling this historic achievement from inception to completion. This is the abridged version for those who want a quicker summarized read of the history, objectives and logistics of the Apollo 11 mission. If you want to get more in the weeds of the day to day decisions and logistics, read the longer version here: https://harfordastro.org/blog-4-1/the-apollo-11-mission

Hopefully you enjoy the journey and gain an appreciation for the hard work and ingenuity that went into the early years of the human age of space exploration.

The Space Race & The Apollo Program

The end of World War II ushered a paradigm shift that thrust the planet into one of two main political factions: the West led by the United States and the East led by the Soviet Union. The advent of nuclear weapons, however, prevented this from becoming a direct conflict and thus these two superpowers competed through economics, technology and proxy wars. One of the most ostentatious of these arenas was what became known as the Space Race.

The Soviet Union made early gains by launching the first artificial satellite, Sputnik 1, and putting the first human into space, Yuri Gagarin. In response, U.S. President John Kennedy tasked the newly established National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) with putting a man on the Moon by the end of the decade. The Mercury and Gemini programs launched numerous missions to build up the engineering capabilities and experience necessary for humans to operate in space. The Apollo missions would follow in rapid, iterative succession to lay the logistical groundwork for Apollo 11.

Fun fact: Apollo 10 went all the way to lunar orbit and almost became the first to put humans on the Moon but the idea was scrapped at the last minute.

Meet the Crew and Spacecraft of the Apollo 11 Mission

Announced in 1967, the astronauts selected for the Apollo 11 mission were Neil Armstrong, Edwin “Buzz” Aldrin and Michael Collins. Each had previously served as U.S. Air Force pilots and participated in the Gemini missions. Armstrong, an Ohio-born aeronautical engineer, led the mission and oversaw the safe execution of its objectives. He was known for his mild-mannered demeanor. Aldrin, a New Jersey native and the first astronaut with a doctoral degree, was set to join Armstrong in the lunar module to land on the Moon. Collins, born in Rome, was to remain in lunar orbit during the lunar surface operations.

The Apollo 11 spacecraft that would take the crew to the Moon and back consisted of three main components: the Command Module (Columbia) was a small aluminum cone that would house the astronauts and contained all the life support, navigation and communication equipment. Its heat shield ensured safe re-entry into Earth’s atmosphere, while a Launch Escape System on top could pull it to safety during a launch emergency. Behind it was the cylindrical Service Module, which provided propulsion to enter and leave lunar orbit. The Lunar Module, a two-stage, insect-like craft with four legs, ferried Armstrong and Aldrin from lunar orbit to the Moon’s surface and back.

To launch Apollo 11, NASA used the Saturn V rocket, the largest and most powerful rocket ever flown, standing 110 meters tall and weighing 6.5 million pounds when fueled. it used liquid hydrogen and liquid oxygen propellants and was divided into three stages, each optimized for its role. Staging allowed the rocket to shed weight as it ascended, ultimately reaching the 11 km/s escape velocity needed to send Apollo toward the Moon. As of 2025, the Saturn V remains the only rocket to have carried humans beyond low-Earth orbit, securing its place as an engineering marvel of the space age.

Launch Day

July 16, 1969

In early 1969, the massive Saturn V rocket and Apollo 11 spacecraft components arrived separately at Kennedy Space Center in Florida due to their enormous size and weight. Some stages were so large they had to be shipped by barge from New Orleans. Once assembled in the Vehicle Assembly Building, the fully integrated rocket and spacecraft underwent final checks before being rolled out in May to Launch Complex 39-A, as Apollo 10 was still on its lunar mission.

On July 16, 1969, launch day began early for astronauts Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin, and Michael Collins, who awoke at 4:00 a.m. to prepare for the historic mission. After donning their spacesuits and boarding the spacecraft, the cabin was sealed and pressurized with pure oxygen. At 9:32 a.m. EDT, the Saturn V roared to life, generating 7.5 million pounds of thrust as flames and smoke engulfed the launch pad. The first stage burned for nearly three minutes, propelling the vehicle to over 6,000 mph before being jettisoned. The second stage then ignited, pushing the craft close to orbital speed, followed by the third stage, which completed insertion into Earth orbit.

By 9:44 a.m., just twelve minutes after liftoff, Apollo 11 was 115 miles above Earth, circling the planet at 17,500 mph. While in orbit around the Earth, the crew conducted system checks and captured photographs, preparing for their journey to the Moon.

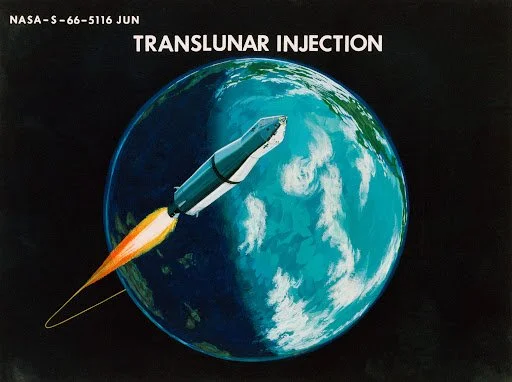

Trans-Lunar Coast

July 16, 1969

After one and a half orbits around Earth, Apollo 11 fired its third stage at 12:16 p.m. EDT for almost six minutes, boosting the spacecraft to 25,000 mph and setting it on course for the Moon. The maneuver, called a translunar injection, marked the start of a three-day journey. Armstrong radioed Houston, saying, “That Saturn gave us a magnificent ride.”

Shortly after, the crew separated the command-service module from the rocket’s third stage and docked with the lunar module. By 1:48 p.m., the lunar module was attached and the third stage was sent into a solar orbit where it likely remains to this day. The astronauts ran system checks, took photos of Earth from 91,000 km away, and shared a live TV broadcast watched by millions.

By the end of the first day, Apollo 11 had covered a great distance but still had 286,000 km to go before reaching lunar orbit on July 19. The crew ate a meal, settled in for the night, and prepared for routine checks and course corrections during the journey.

Lunar Orbit Insertion

July 19, 1969

About 55 hours into the mission, Armstrong and Aldrin moved into the lunar module. After preparations, the crew rested as the spacecraft entered the moon’s gravitational influence and began accelerating. When they woke on July 19th, the Moon appeared enormous, and they briefly saw star constellations and the Sun’s corona before passing behind the Moon and losing contact with mission control.

Later, the crew performed a crucial engine burn to slow down and enter lunar orbit, first into an elliptical path, then into a nearly circular one about 110 km above the surface. They spent time observing the landing area, checking systems, and moving equipment into the lunar module. They signed off for sleep at 12:04 a.m. EDT on July 20th.

Lunar Module Descent & Landing

July 20, 1969

On July 20th, 1969, Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin entered the lunar module, powered it up, and prepared for landing. In the afternoon, the lunar module, now named “Eagle,” separated from the command module Columbia, piloted by Michael Collins. After a quick inspection, Eagle performed a burn to lower its orbit to about 15 km above the Moon, setting up for descent. In Houston, tension was high as the landing attempt began.

The powered descent started automatically, but problems soon appeared. Eagle was descending faster than expected because of navigation issues, and alarms went off in the cabin. Armstrong saw they would miss the intended landing site by several miles and had to take manual control. Fuel was running dangerously low as he searched for a safe spot, steering the lander over a crater and boulder fields.

With less than 30 seconds of fuel left, Armstrong found a clear area and guided Eagle down through a cloud of lunar dust. At 4:17 p.m. EDT, the lander touched down smoothly. Armstrong then reported to Houston: “Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed.” The control room erupted in relief. Humanity had successfully landed on the Moon.

Lunar Surface

July 20, 1969

After landing at what was now known as “Tranquility Base,” Aldrin described the barren gray landscape to mission control while he and Armstrong stayed inside the Eagle for over six hours. Though a rest period was scheduled, both men were too excited to sleep and instead ran through post-landing checklists and a simulated ascent countdown to ensure the lander was functional. They received approval to begin the EVA four hours early.

Suiting up inside the cramped, cluttered cabin took more than three hours, and exiting through the narrow hatch proved challenging. Armstrong squeezed through and climbed down the ladder, activating a camera on the exterior of the lunar module so the world could watch live.

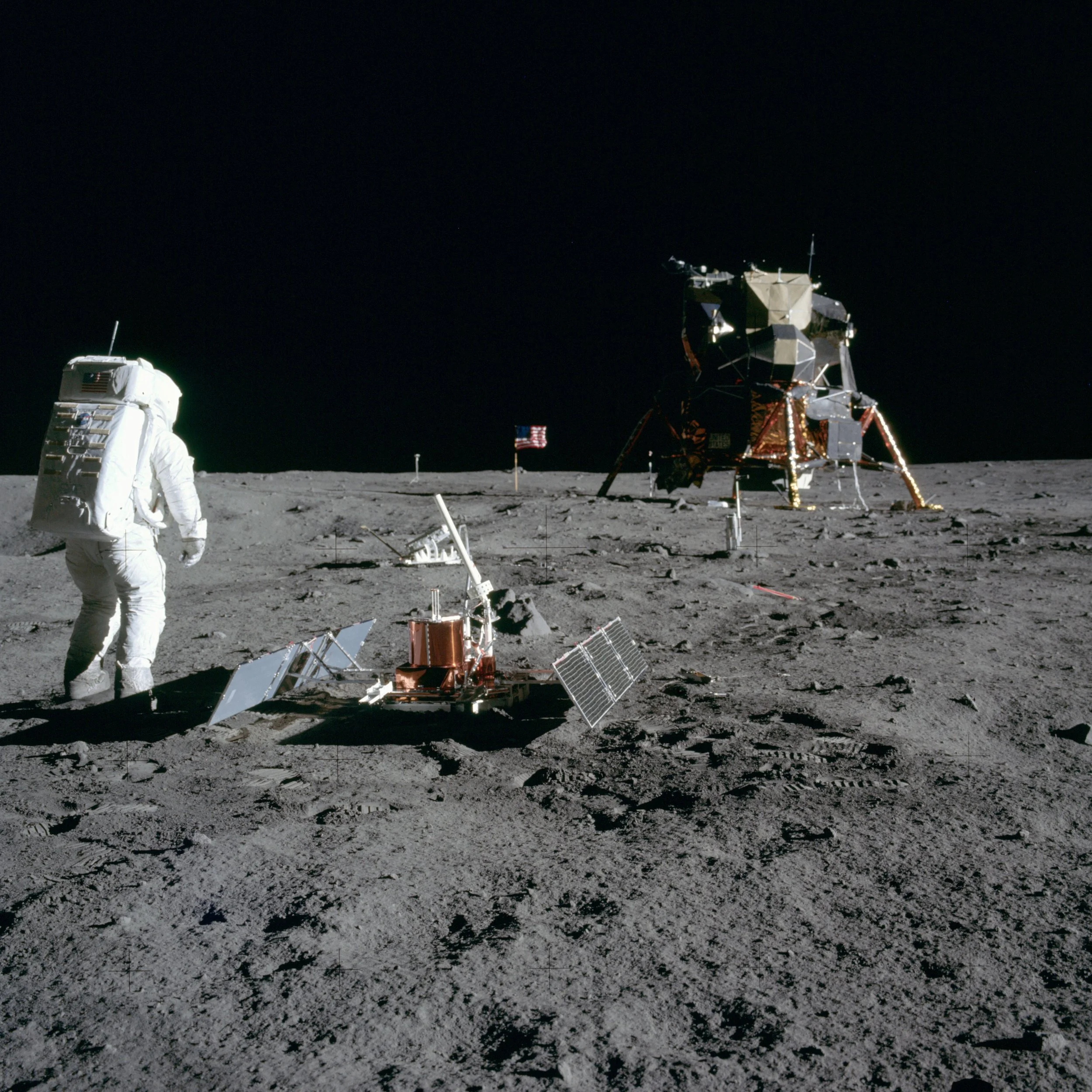

At 10:56 p.m. EDT on July 20th, 1969, Neil Armstrong planted his left boot on the lunar surface and declared, “That’s one small step for [a] man, one giant leap for mankind.” Aldrin followed about twenty minutes later, marveling at the “magnificent desolation” surrounding them. It was noted that the fine, powdery regolith blanketing the lunar surface clung to everything and made the rocks slippery.

Lunar gravity made movement easy yet required care for balance, especially with heavy backpacks. Aldrin tested different gaits, including a hopping technique, but found standard steps worked best. The astronauts deployed the American flag about forty minutes into the EVA and saluted as President Richard Nixon called from the White House, praising their achievement as a moment of unity for the world.

Science objectives were limited because Apollo 11 was basically a test mission. The Early Apollo Scientific Experiments Package (EASEP) included a solar wind collector, a passive seismometer, a laser retro-reflector, and a dust collector. These provided data on solar wind composition, lunar seismic activity, and precise Earth-Moon distances. These measurements are still ongoing today. Armstrong and Aldrin also collected 47.5 pounds of rocks and soil, mostly ancient basalt, despite difficulties driving core tubes into cohesive soil. These samples remain stored at NASA facilities and are studied worldwide.

Before returning, Armstrong revealed a plaque reading: “Here men from the planet Earth first set foot upon the moon. July 1969 A.D. We came in peace for all mankind.” With time running short, he made a quick trip to Little West Crater while Aldrin gathered core samples. After just over two hours on the surface, they climbed back into Eagle, sealed the hatch, and began preparations for liftoff. They noted a burnt gunpowder smell coming from the regolith stuck to the outside of their suits. Exhausted after nearly 21 hours awake, they finally tried to sleep in the cold, noisy cabin.

Lunar Module Liftoff, Ascent & Docking

July 21, 1969

When preparing to leave the Moon, Buzz Aldrin discovered that a broken circuit breaker could have stranded them there. Using a felt-tip pen, he managed to activate the ascent engine of the Lunar Module, allowing them to take off. The ascent engine fired, using the descent stage as a launch pad. Armstrong famously said, “The Eagle has wings,” as they left Tranquility Base and climbed back into orbit with far less thrust than was needed to escape Earth’s gravity.

Once in an elliptical orbit, Armstrong and Aldrin had to rendezvous with Michael Collins in the Columbia. This maneuver required precise navigation with very limited fuel, relying on preparation, practiced techniques from the Gemini and Apollo missions, and tools like the Rendezvous Radar. Over two orbits and three and a half hours, they used the “coelliptic method” to gradually match Columbia’s path.

Docking wasn’t entirely smooth due to attitude issues and sun glare, but the crew eventually connected and transferred moon rocks, films, and equipment. With everything ahead of schedule, Houston authorized them to jettison the Eagle early. At 7:41 p.m. EDT, explosive charges separated the ascent stage, leaving it to orbit briefly before crashing into the Moon. Its final signal was received at 2:24 a.m. on July 22nd, marking the end of its historic journey.

Trans-Earth Injection

July 22, 1969

The three astronauts of the Apollo 11 mission were reunited. All that remained of the Apollo 11 spacecraft was the Columbia command-service module. The only objective remaining in the mission was to get these three men home safely. On their 31st orbit around the moon, Columbia fired its main engine, using a big burn to send the spacecraft toward Earth. This maneuver pushed them to about 5,900 mph, starting a 60-hour trip back. During the burn, the crew saw Earthrise one last time over the moon’s surface.

As they moved away, the astronauts watched the moon shrink and measured its size to track their distance. While Columbia headed for Earth, the moon continued circling our planet at about 1 km per second.

Return to Earth

July 24, 1969

In the last hours before reentry on July 24, 1969, the Apollo 11 crew took photos of Earth as they got closer, from 63,000 km away in the morning to just 19,000 km by early afternoon. Before entering the atmosphere, they separated the command module from the service module using explosive charges, leaving the empty service module to burn up later.

Apollo 11 hit the atmosphere at 24,250 mph, generating temperatures of 5,000°F that the heat shield was designed to handle by burning away safely. Radio contact was lost for nine minutes during this fiery descent. Once the capsule slowed enough, small parachutes opened, then three large ones, bringing the spacecraft down to splash into the Pacific Ocean at 12:50 p.m. EDT, about 400 miles from Wake Island. Recovery crews from the USS Hornet picked up the astronauts, who wore protective suits as a precaution against possible lunar germs, and placed them in a quarantine trailer.

The astronauts stayed in quarantine for 21 days before being cleared. Then came celebrations: a big press conference on August 12th, a ticker-tape parade in New York, more parades in Chicago and Los Angeles, and a dinner hosted by President Nixon, who gave them the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Later, they spoke to Congress and went on a seven-week world tour to 24 countries, sharing the success of the moon landing as a victory for all humanity.

The Legacy of Apollo

Between 1969 and 1972, NASA’s Apollo program sent six missions to the Moon, allowing twelve astronauts to walk on its surface. Each mission built on the success of the last, with Apollo 12 proving precision landings possible. Later missions extended stays, explored new regions, and introduced the Lunar Roving Vehicle, enabling astronauts to travel farther. The final mission, Apollo 17, included geologist Harrison Schmitt, set a record for time spent on the lunar surface, and gave the world the famous “Blue Marble” image of Earth.

Meanwhile, the Soviet Union’s attempts at crewed lunar missions failed due to the unreliable N1 rocket, which suffered multiple catastrophic explosions before the program was canceled in 1976. Despite this, the Soviets scored later successes with automated sample returns and Lunokhod, the first lunar rover.

The Apollo program not only marked a major political victory for the United States but also sparked innovation, leading to advances like miniaturized computers, solar panels, cordless tools, and memory foam. It inspired a generation of scientists and fostered a global sense of unity through images like Earthrise, which helped fuel the environmental movement and the concept of the “Overview Effect.”

Despite all these transformative effects, the perceived defeat of the Soviet Union in the Space Race diminished the political drive to return to the Moon and humans haven’t returned since 1972. However, NASA’s Artemis program aims to change that by establishing a sustainable lunar presence as a stepping stone to Mars. Artemis 1 successfully tested key systems in 2022, and Artemis 2 will carry astronauts around the Moon as early as September 2026, setting the stage for the next era of space exploration.