MERCURY

The closest planet to the Sun.

Distance from the Sun: 58 million km (0.4 AU)

Diameter: 4,880 km

Rotation period: 59 days

Orbital period: 88 days

At about only a third the size of Earth and only slightly larger than the Moon, Mercury is the smallest of the solar system’s eight planets. It is the second densest planet in the solar system, just slightly behind Earth. It has a disproportionately large iron core compared to the other terrestrial planets, making up about 57% of the planet’s volume. The core is surrounded by a layer of silicate rock that acts as the planet’s surface. There are a few hypotheses as to why the core is so much bigger than its mantle. Many scientists believe the rocky shell was chipped away by numerous collisions over time, but more recent ideas are that the Sun’s powerful magnetic field pulled iron molecules inward early in the solar system’s formation.

Mercury’s close proximity to the Sun requires an equally fast orbit to keep from falling in. The planet goes around the Sun in only 88 Earth days, the fastest orbit in the solar system. This is why Mercury is named after the fleet-footed messenger god in Roman mythology. Also, because Mercury is so close, the Sun appears three times as large in its sky as it does on Earth and 11 times as bright.

Another interesting quirk of Mercury’s orbit involves tidal forces (the stretching of an object via gravity). Just as the Earth exacts a tidal force on the Moon and vice versa, so too does the Sun exact a tidal force on the planets, with Mercury feeling this force the strongest. For the Moon, this causes it to become tidally locked where the same side is always facing the Earth. However, Mercury’s orbit is highly eccentric, meaning it varies greatly in distance throughout a single revolution around the Sun and thus orbits faster and slower. The end result is not tidal locking but a 2:3 spin-orbit resonance, rotating on its axis exactly three times for every two revolutions around the Sun.

Because it is closer to the Sun than Earth is, Mercury regularly passes between the two. Most times, the 7° incline of Mercury’s orbit (the most of any planets in the solar system) puts it too far above or below the Sun to be visible. It is rare, but every once in a while, the three bodies will line up just right and Mercury will appear to cross right in front of the Sun from our vantage point. This is called a transit and for Mercury it happens about 13-14 times per century. With the proper protection, astronomers can witness this happening through even small telescopes.

Note: Never look directly at the Sun without approved solar glasses or a solar telescope filter. Otherwise, you could risk permanent eye damage and/or blindness.

Looking at the Mercurial surface, you’ll likely see a barren expanse of rocky craters and not much else. For the most part, that’s all there is. Of all the planets, Mercury most resembles our Moon. There isn’t significant geological activity such as earthquakes or mountain formation, though much of the surface is covered in lava plains (similar to the Moon’s maria) but no volcanoes which suggests past volcanism which has long ago ceased. The planet doesn’t seem to be divided into moving tectonic plates like we see on Earth, but there are signs that the surface was shaped by ancient contractions when the interior was still cooling down.

Despite its substantial iron core, Mercury’s magnetic field is only 1% the strength of Earth’s and not quite strong enough to protect it from meteor bombardment. The craters range in size from small cavities to massive impact basins, the largest being the Caloris Basin, which spans about 1,525 km and ringed by 2 km high mountains.

Many of the craters on Mercury are named after writers, artists and musicians such as Shakespeare, Van Gogh and Beethoven.

Mercury has the most extreme range of temperatures of any planet. Being so close to the Sun puts Mercury’s surface at a scorching temperature of 430°C (800°F) on the day side. Mercury does have a very faint exosphere, a thin collection of atoms blasted off the surface by striking meteoroids and solar wind. It’s nowhere near enough to maintain the blistering heat of the day side, however, so Mercury can get extremely cold at night, dropping as low as -290°C (-180°F).

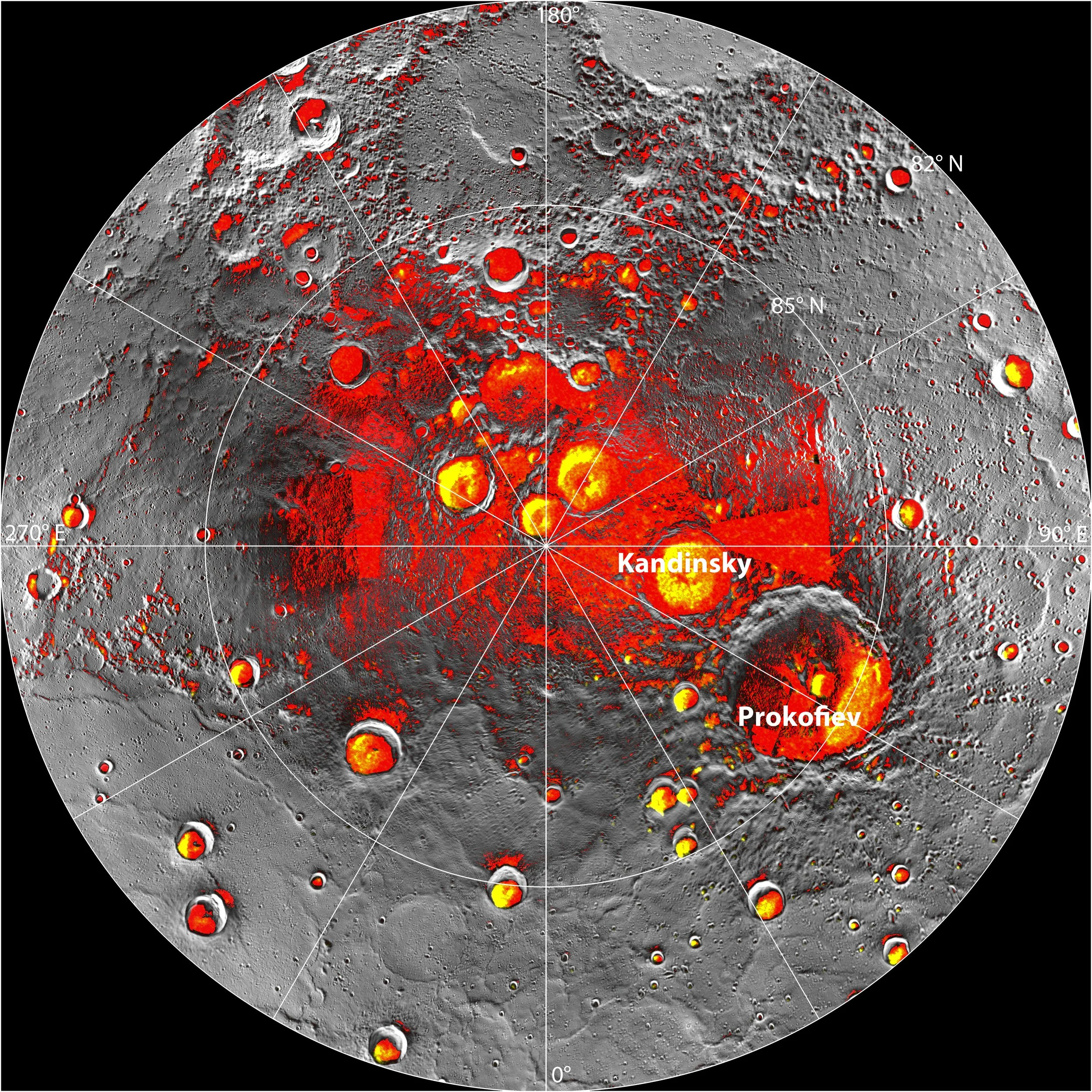

Due to Mercury having almost no axial tilt, there are places deep within craters at the poles that are permanently steeped in shadow that form large reservoirs of water ice!

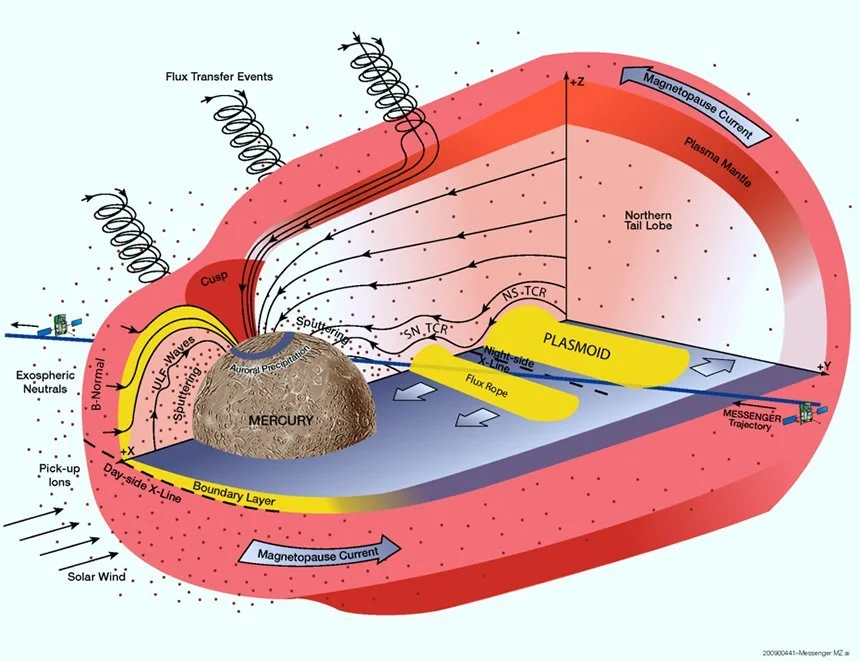

As Mercury is so close to the Sun, the solar wind is particularly punishing. So much so that it frequently twists the planet’s magnetic field up into coils, or colossal magnetic tornadoes. Scientists call these “magnetic flux transfer events.” The solar wind rides the coils of these magnetic tornadoes and slam into the surface, lifting atoms up high into the sky and then Mercury’s gravity pulls them back down. These tornadoes can sometimes be as wide as the entire planet. It is now hypothesized that these invisible magnetic storms actually feed Mercury with material for its very thin, patchy atmosphere.

Solar wind from the Sun and micro-meteorites that hit the surface, eject sodium atoms entrenched within Mercury’s soil and blast them out into space. This forms a golden tail of sodium gas that is around 24 million kilometers long.

It is only possible to see Mercury’s sodium tail for yourself under certain conditions. This requires the ability to take long exposure images and a special filter. Specifically, a 589 nanometer filter is attuned to the golden glow of sodium. Hint: The tail is brightest when Mercury is within 16 days of perihelion (when it is closest to the Sun).